The JRB presents an excerpt from My Mother’s Laughter: Selected Poems by Chris van Wyk, edited by Ivan Vladislavić and Robert Berold. See below for a video of van Wyk reading the collection’s eponymous poem; and the end of this excerpt for a video from the book’s launch.

Chris van Wyk’s first and only book of poetry, It Is Time to Go Home, was published in 1979 when he was just twenty-two. He went on to become a well-known and much-loved writer of memoirs, biographies, and children’s stories. But he continued to write poems; some were published in literary magazines, some in his autobiographical Shirley, Goodness & Mercy (2004).

This volume brings together a selection of these poems, along with a substantial selection from his first book.

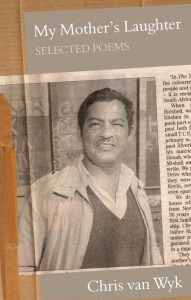

My Mother’s Laughter: Selected Poems

By Chris van Wyk, edited by Ivan Vladislavić and Robert Berold

Deep South, 2020

Introduction

by Ivan Vladislavić

For much of the nineteen-eighties, Chris van Wyk was the editor of Staffrider. This literary and cultural magazine was established at Ravan Press in 1978 in response to the new writing that emerged after the Soweto student uprising—‘the great surge of creative activity which has been one of the more hopeful signs of recent times’, as the first editorial put it.

While the focus was on new voices, rooted in community cultural groups, the magazine also attracted a wide range of ‘unattached’ contributors, producing poetry, fiction, popular history, graphics and photographs. The young Van Wyk, who had already published a collection of poetry and started his own literary magazine Wietie, took over the reins of Staffrider in 1980 and brought his own ideas to it.

When I joined the press a few years later, Chris was the first person I got to know. On my first morning in the job, he offered to show me around and soon set me at ease. Ravan operated out of an old house in O’Reilly Road in Berea and an outbuilding served as storage for the overflow of books. Chris took me up a wooden ladder into the attic of this storeroom, which was piled with books and magazines. As he began to speak about his work, it became clear that for him Staffrider was the heart of the enterprise.

Many readers would have agreed. Although the press had a diverse publishing list, ranging from children’s books to academic history, Staffrider had a unique magnetic appeal. Young writers from all over the Reef arrived at the door, clutching poems or stories handwritten in exercise books or on scraps of paper. Chris spent part of nearly every day at the kitchen table or on a bench in the back yard, going over edited pages with these visitors. Editing had been kept to a minimum in the early days of the magazine, but by now Chris was intent on improving the quality of the work he published, and poured his energies into the task. He became a mentor and friend to countless emerging writers and artists.

*

Watch: Chris van Wyk reads his poem, ‘My Mother’s Laughter’, at the 2007 Spier Poetry Festival outside Cape Town, South Africa.

*

Chris van Wyk was born in Johannesburg in 1957, the eldest of six children. After a few years in Newclare, his family moved to Riverlea, a small coloured township between the city and Soweto, loomed over by a mine dump. He would spend much of his life in Riverlea, which he later described as a ‘forgotten township’.

His first poems were published in the Star newspaper in 1975 when he was still a matric student at Riverlea High School, and he continued writing and publishing through the intense political and cultural ferment of the Soweto uprising of June 1976. Recalling this time decades later, he asserted: ‘I am of the 1976 generation of poets.’

His early work was shaped by the Black Consciousness movement and was defiant in its call for resistance and change. Alongside these forceful political poems, he also produced tender, sensual love poems, many dedicated to his high-school sweetheart Kathy (they married in 1980 and had two sons, Kevin and Karl).

He showed his first writings to poets Stephen Gray and Robert Greig, who gave him advice and encouragement. His debut collection, It Is Time to Go Home, published by Ad Donker in 1979 when Chris was twenty-two, announced him as a writer of unusual promise, and won the Olive Schreiner Prize.

Despite this early recognition, Chris’s focus moved away from poetry. In 1982, he published A Message in the Wind, a children’s book that won a Maskew Miller Longman award. Many other books for children followed over the years, including widely read tales like Petroleum and the Orphaned Ostrich and Ouma Ruby’s Secret.

In the late nineteen-seventies, he worked for the South African Committee for Higher Education (Sached) writing material for newly literate adults, a job he left in 1980 to found the literary magazine Wietie with his friend Fhazel Johennesse. Later that year, he went to work for Ravan Press.

He was passionate about promoting literacy and reading, and never turned down an invitation to speak to schoolchildren, who were enthralled by his stories and his infectious way of telling them. After the advent of democracy, a publisher commissioned him to write a series of short readable biographies of prominent figures in the South African political struggle. These were prescribed in schools and led to unexpected financial success, allowing him to give up his work as a freelance editor and write full-time.

The following years saw the publication of his memoir Shirley, Goodness & Mercy (2004) and its sequel Eggs to Lay, Chickens to Hatch (2010), which put Riverlea on the map and brought him a wide readership. While he enjoyed the acclaim, what mattered most was the local response, the reactions of old schoolfriends, neighbours, shopkeepers. He loved telling how people contacted him to correct a detail or challenge a conclusion, or—best of all—to complain that they weren’t in the book.

Chris’s other publications included the novel The Year of the Tapeworm (1996), an English translation of AHM Scholtz’s Vatmaar (2000), and a biography of the activist Bill Jardine, Now Listen Here (2003). He was also commissioned to abridge Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom for young readers. He was working on a novel when he died of cancer in 2014.

*

Although he continued to write poetry into the nineteen-nineties, Van Wyk did not publish another collection after It Is Time to Go Home. He incorporated ten poems into his memoirs—five of them from the It Is Time volume—using them to tell parts of his story and describing the contexts in which they were written. This selection aims to present the best of this published and unpublished work to new readers, and to older readers who are only familiar with the long-out-of print first collection.

The qualities that make his prose so engaging are also evident in his poetry. He was drawn to aphorisms and puns and adroitly extended metaphors or plays on words. He also had a gift for capturing a child’s view of the world, and some poems are imbued with a childlike sense of wonder that transcends the cute and sentimental.

He was a wonderful storyteller, acutely observant and attuned to how South Africans speak. He was alive to the world of working people—some of his most memorable stories and poems play out in taxis and train compartments—and he knew how to capture the spontaneity and earthiness of a spoken story on the page.

All this makes for memorable writing: lines and images stick in the mind years after they have been heard or read. Several poems, including ‘A Riot Policeman’, ‘About Graffiti’, ‘We Can’t Meet Here, Brother’ and ‘The Ballot and the Bullet’ have been widely anthologised. ‘In Detention’ has found its place in the South African canon and the popular memory: with its chilling permutations, it remains one of the starkest indictments of apartheid’s duplicity and brutality in our literature.

~~~

Watch a video of the book’s virtual launch: