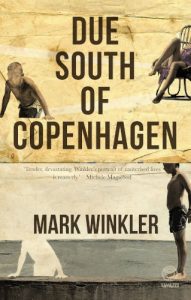

The JRB presents an excerpt from Due South of Copenhagen, the new novel from Mark Winkler.

Due South of Copenhagen

Mark Winkler

Umuzi, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

We’d got to be friends, Karl Udengaard and me, mostly because of the Nazis. You couldn’t get a surname more German than Fritz. I didn’t even need a nickname. Just ‘Fritz’ would do. Unless it was ‘Fritz Fritz’. That Karl’s surname was Danish didn’t matter to the other kids. It sounded German unless you knew better, or cared. It didn’t help that Ove Udengaard spoke German to old Willie Fritz, or that Willie Fritz’s German accent clung fast even after twenty years. The War had ended more than thirty years earlier but the resentments were fresh. Even out here in the bush, nine thousand miles from the battlefields of Europe, every boy had a grandfather or an uncle who’d fought the Jerries, or died by them. Every boy had a Bren gun made out of a bluegum stick or fresh air and an endless supply of make-believe hand grenades on his belt. Every boy believed the entire German language was made up of the words ‘achtung’ and ‘schweinhund’.

One day, when Hulk Vermaak was beating me up, again, for being a stinking Kraut, the new boy Udengaard came up and brained him with a hockey stick. Someone phoned Vermaak’s mother and someone else took him to hospital for stitches. We were dragged off to the headmaster, Karl Udengaard and me. Old Skilpad Vermeulen said he would have expelled us if he could have, but he couldn’t because there was no other school for us to go to, and what with the year-end exams upon us any day now. I could hear Karl’s narrow Nordic nose going like a wheezy air filter while Skilpad Vermeulen lectured. Then Vermeulen made a show of selecting the whippiest cane from the dozen or so in the stand behind his door, taking them out one by one and bending them one way and the other, slashing them this way and that, forehand and backhand like he was playing squash, while we watched. First Karl had to bend over and hold the armrests of the chair while Vermeulen gave him six of the best, and then it was my turn. He took his good time between each stroke, Vermeulen did. You could hear that cane whistle through the air before it hit, and the sound told you how much it would hurt. I didn’t really cry afterwards, hopping up and down and rubbing my arse in the corridor outside Skilpad Vermeulen’s office, but Karl looked at me with those cold, dry northern eyes and he lifted a corner of his lip and punched me on the shoulder so hard the muscle twitched. ‘Harden up, Fritz, for fuck’s sake,’ he said and stalked off.

Next Saturday Karl Udengaard appeared at Willie Fritz’s garage on his shiny Chopper. It wasn’t even nine o’clock and already the cicadas were going. The Idiot was sweeping the forecourt, stirring up clouds of dust with his broom, making everything dirtier instead of cleaner, but there was no use stopping him. Every now and then Samson stood up from his oil drum to fill up a car. Or else he just sat there, smoking those cigarettes he made by rolling Boxer tobacco in strips of newspaper. Me, I was sitting in the shade on the old Valiant seat we used as a bench, the dog at my feet. Reading a book, a Louis L’Amour or a Wilbur Smith or something. Manny the Porra let me borrow the second-hand books from the bookstand in his café for free, and sometimes the comics too, as long as I gave them back in good nick and cleaned the carburettor of his Kombi every now and then.

Karl came skidding broadside to a stop and kept his hands on the handgrips, probably because he thought it looked cool, like Jack Nicholson on a Harley or something. The Idiot stopped sweeping and gaped.

‘What?’ Karl said and the Idiot pulled his head down between his shoulders and began to gnaw at the end of his broom handle. Then Karl looked at the book in my lap. ‘Reading is for girls,’ he said. ‘Come. I want to show you something.’

I went into the workshop where Willie Fritz was tinkering under the bonnet of a Datsun and Esmé Euvrard played pop music in between the messages she read to the army boys over the radio on the windowsill and I told him I was going off. Then I fetched my bike, a heavy old black thing with a rattly carrier and a chrome headlight that didn’t work and backpedal brakes that sometimes did, and I followed Karl down the tar road, the dog cantering alongside on the gravel shoulder where the timber trucks and the Chev Impala taxis wouldn’t get him, and when we got to the ou Farms sign we turned off and went on up the farm track.

The Udengaards grew mostly oranges and grapefruit, acres and acres of them, with a few rows of mango trees at one end and some avocados and pecans at the other. If you went past the place in spring, the scent of orange blossom was so thick you could just about taste the air and the whole world smelt womanly and warm. Now the blossoms had turned to fruit, and little oranges clustered hard and green in the trees beside the track.

Karl had three gears on his bike and I had none. Also, he was taller than me, scrawny as a runner, muscles like rope tight under his skin. I caught up to him where the farm track forked. He stood away from the Chopper, flicking gravel chips into an orange tree with a finger.

‘Jesus, Fritz,’ he said. ‘Come on.’ He flicked a stone at me and it stung my thigh and then he got on his bike and pedalled off. I followed him and a few minutes later I reached a dam, the dog and me, Karl waiting for us on his bike. He got off and kicked out the stand and balanced the Chopper in the dirt. The dog ran to the water to drink and splash around. I picked up a stick and slashed at the long grass. You had to be careful of snakes out here, especially in summer, the mambas and puff adders and cobras and things. The grass let off its hot, sweet smell of baking earth and summer dust. Then I wagged the stick under the dog’s nose and threw it out into the brown water. The dog looked at the splash and looked at me and did nothing.

‘That’s one stupid dog,’ Karl said.

I didn’t know about that. ‘What do you want to show me?’ I said.

~~~

About the book

A letter bearing news of boyhood friend Karl Udengaard’s death sets Maximilian Fritz on a path of disconcerting reminiscences on his last day as editor of a community newspaper.

Growing up as the son of a petrol-station owner in a Lowveld town, 12-year-old Max is bashed around and bullied – until the arrival of Karl Udengaard. Karl teaches Max how to toughen up, while Max’s feelings for Gunna Udengaard, Karl’s enigmatic mother, rage in secret.

Tragedy severs Max’s ties with the wealthy Udengaards. As the decades-old memories unravel, he begins to comprehend his own complicity in his and their misfortunes.

Due South of Copenhagen is a masterful tale of the scope of intimate connections between people, small-town living during the height of South Africa’s Border War, and what it takes to put the past to rest.

About the author

Mark Winkler is the author of the critically acclaimed novels An Exceptionally Simple Theory (of Absolutely Everything), Wasted, which was longlisted for the 2016 Sunday Times Barry Ronge Fiction Prize, The Safest Place You Know and Theo and Flora, which was shortlisted for the 2019 Barry Ronge Fiction Prize.

His short story ‘When I Came Home’ was shortlisted for the 2016 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and ‘Ink’ was awarded third place in the 2016 Short Story Africa competition.