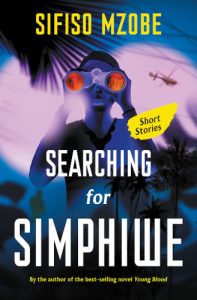

The JRB presents an excerpt from ‘The Worst That Could Happen’, a short story by Sifiso Mzobe, from his new collection Searching for Simphiwe. Read an early version of the title story, which we published in September 2018, here.

Searching for Simphiwe and Other Stories

Sifiso Mzobe

Kwela, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

The Worst That Could Happen

Hopeless, that’s how Siya feels. Useless, and full of dread.

He scrolls down his cellphone until he hits Makhendlas’ digits. He is Siya’s only hope now. If Makhendlas can get him a job at the logistics company where he works, Siya will be all right. That company pays good salaries. But Siya’s call goes straight to voicemail.

He sends Makhendlas a WhatsApp:

Please, Makhendlas, don’t forget

about me. If a job comes up call

me. Please.

Siya

Perhaps he shouldn’t have texted ‘Please’ twice. Was that too desperate?

Siya can’t believe he is in the pit of hopelessness again. He thought the year after he graduated was the darkest ever. Three hundred and sixty-five days of waking up without any job prospects. But now he is in the same situation after three short-term employment stints.

He scrolls his phone until he finds Lunga. On a day like this, when he wakes up in a negative state of mind, he can do with his best friend’s jokes and never-say-die attitude.

True to form, Lunga answers with a laugh and booming voice.

‘Howzit, Siya, my brother?’

‘Sho, Lunga. How’s it going with you? Things are bad on my side. Kunswempu ngempela, mfwethu.’

‘Same here, Siya. I have sent applications everywhere, but not one reply yet. But something will come up sooner rather than later, bro, don’t worry,’ says Lunga.

‘Where are you? You sound like you’re running.’

‘Hhayi, no Siya, I am digging trenches. My uncle got me a job at the company he works for. It’s back-breaking work for just R88 a day.’

‘R88—that’s crazy! Can you even buy yourself anything with those peanuts they pay you?’

‘You should have seen the look on my mother’s face when I told her I was taking this job,’ says Lunga laughing. ‘She looked like I just told her a relative had passed away. She was that disappointed.’

‘Yhu, Lungs!’

‘I overheard her talking to her best friend on the phone: “Our children graduated university for this? What has the country gone to? Yazi uyasihlanyela uhulumeni, mina ngizoqonda khona eUnion Buildings ngibatshele ukuthi bangadlali ngezingane zethu”,’ says Lunga mimicking his mother’s shrill voice, sending Siya into giggles.

‘I think she is embarrassed to tell people where I work. But I don’t blame her. Who’s heard of a business management graduate digging trenches?’

‘Or a business management graduate pleading with a connection like Makhendlas to get him an interview. After a year of doing fuck all?’

‘No, it is really bad, Siya. And everyone is telling the same story. Unemployment is an epidemic in South Africa. There are simply no decent-paying jobs.’

‘Anyway, Lunga, how come you finally took the job shovelling dirt?’ says Siya. ‘I thought you said it was beneath you.’

Lunga laughs. ‘You know how it is. Months were dragging by and nothing was coming up. I just grew tired of asking Ma for cash for everything. And I could no longer stand rolling on the couch all day. With this job I have money for airtime and toiletries, at least. Do you know how embarrassing it is to be a grown man asking for money to buy roll-on? With the pay from this job I also have cash to scan my certificates and email my CV.’

‘I hear you, Lungs, that’s true. As it is now, I am staring at my last R50,’ says Siya looking down at the dirty note in his hand.

‘Hey, if push comes to shove, you can come here and dig trenches with me just to get out of the house.’

‘The way things are going, I am seriously considering it.’

‘Before I forget, there’s a party at Zakwe’s in the suburbs this weekend. I will pick you up around one in the afternoon on Saturday. Zizowa strong, abantwana bazobe bechithiwe!’

‘How can you think of parties in situations like these, Lunga? I am in no mood to party.’

‘Hey, Siya, you have to get out of the house otherwise worries will kill you.’

‘Okay, okay, I’ll see you on Saturday then.’

‘Got to go, Siya, the site manager is looking at me funny,’ says Lunga, ‘We’ll talk later.’

Siya hasn’t played music on the sound system in his room in a while, but after the chat with Lunga he switches on an upbeat tune and busts his best moves in front of the mirror. Maybe a party isn’t such a bad idea. He looks around his room and is proud of all the appliances and clothes he bought in the thirteen months he was working: the LG sound system, an LED TV and a second-hand laptop that is almost as good as new. He is thankful for the stint as a taxi driver that got him into the job market – work he took when he was utterly desperate – followed by the three months he covered for a manager at a catering company that was on maternity leave. If only the small construction firm where he worked as project manager for seven months had not gone under. He made life at home comfortable while he was employed. They were never behind on utility bills, and food was always plentiful in the fridge.

Now that work has dried up, he is feeling the strain again. He switches the music off.

From his separate-entrance room in the backyard, Siya walks into the main house. His mother is sitting at the kitchen table, a pot of Jungle Oats boiling on the stove. She rubs her arthritic joints. Her eyes are on the electricity meter where the units have almost run out.

‘With the electricity that has gone up again, we’re getting much less for our money,’ she says.

‘Worse is to come, Ma. I read somewhere they will hike it up again next year.’

‘I pray every day that you get a job, my boy. Life was so much better when you were working, we had more than enough,’ she says, staring out the kitchen window with sadness in her eyes.

Siya hates it when she gets like this.

‘Something will come up, Ma, sooner or later,’ says Siya, removing the pot from the stove because it is starting to burn.

‘I will sing my praises to God when that day comes,’ she says, getting up to dish the oats. ‘Do you want to eat?’

‘No, Ma, I am fine.’

‘Will you go to the spaza shop to buy us an electricity recharge voucher? Here is R30.’

‘I’ll go.’ He wishes his mother didn’t have to use her disability grant money to buy them electricity.

Worries crowd into Siya’s head again as he walks down the road. He has a pounding headache. There are headache tablets at the spaza shop. He stops in his tracks when his phone rings.

‘Tomorrow at ten,’ says the hoarse voice of Makhendlas at the other end of the line.

‘Tomorrow at ten? What is happening tomorrow at ten?’

‘You are wasting my airtime with these questions. Meet me tomorrow morning at ten at the main gate of the place where I work. I have organised an interview with my supervisor. Don’t be late,’ says Makhendlas.

Tomorrow at ten his life will change. Siya doesn’t buy headache tablets. He’ll save his last R50 to get to the interview.

~~~

About the book

Detectives in pursuit of criminals, a brother desperate to find his wungaaddicted sibling, a search for abducted girls, a quest to be reunited with a longlost lover – these are just some of the searches that form the basis of the stories in this collection. On a more metaphysical level there are characters seeking some form of faith or purpose. Entertaining tales that keep the reader enthralled with tension and suspense, while reflecting the realities of contemporary South Africa.

About the author

Sifiso Mzobe was born in Umlazi Township, Durban. He studied journalism and currently works as a freelance journalist. His debut novel, Young Blood, won the Sunday Times Fiction Prize, the Herman Charles Bosman Prize, a SALA, and the Wole Soyinka Prize.