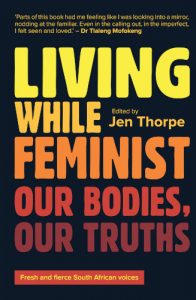

The JRB presents an excerpt from Living While Feminist: Our Bodies, Our Truths, a new collection of essays edited by Jen Thorpe.

Living While Feminist: Our Bodies, Our Truths

Edited by Jen Thorpe

Kwela, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Attitude Problem

Neliswa Tshazi

Becoming

At the beginning, it wasn’t called feminism. It was called an attitude problem. I informed my mother that I disliked cooking and had no interest in learning. My precious mother tolerated this, in spite of disapproval by the rest of the family and neighbours. She did not force me as any mother would have. Instead she allowed me to be the bookworm I am and gave me space as well as support to pursue my studies.

It continued with refusing to be called someone’s girlfriend. I now understand that what I meant was that I didn’t want to be owned. I wanted to be my own person, not to be told what to do or how to be, especially by a man. It also meant not taking kindly to a man arguing or validating his utterances with ‘because I am a man’. Now I am struggling with the idea of marriage. It gives me a suffocating feeling, like I will be placing myself in a position of submission.

As an adult, I always found myself effortlessly, willingly and intentionally in the defence and protection of women in all matters. I wanted (I still want) people to be as they wish and feel. However, for a long time, I would dispute it when my university friends would refer to me as a feminist. University was also the first time I would be named as one. I didn’t want a label.

I did not think I could be called a feminist because I viewed feminists as these well-educated, well-read, and intelligent thinkers—people who knew things I did not know and probably could never know. I could not identify myself that way and I did not know when this would happen to me or when I would reach such levels. It didn’t help that I was not quite sure what it meant to be a feminist. I also do not know why I did not eagerly pursue understanding the concept; maybe I did not want to find out.

I realise now that that understanding was based on a singular story of feminism that I had somehow accessed. My understanding has been expanded, particularly on African feminisms. I know in my heart that I am an African feminist, whether I say or acknowledge it or not. That doesn’t mean the label comes without reservations and confusion.

Unlearning and learning: eschewing the ‘perfect’ feminist

My current and intermittent reservation on being named a feminist is how aggressive people on social media tend to be to feminists, including social media feminists to other feminists. It is as if there are people waiting to pounce on others the minute you say or type something unpopular or disagreeable. There is an expectation of perfect or pure feminism; no room for error and differing perspectives.

I get that when you are a feminist you have to consciously politicise yourself; this happens through reading, engaging, writing, in the process of learning, unlearning and relearning. This then makes it possible to have expectations on the tone and kinds of conversations and behaviour for a feminist.

However, it sometimes feels that we do not fully acknowledge the impact of existence in a world that normalises patriarchy and how deeply entrenched it is in our societies and within us. Patriarchy is such a part of our lives that sometimes we may not be aware that we have enacted it or that our thinking is saturated within it. Such unlearning takes time.

Alongside the leaps and progress made, learning is a process that has to be approached with a level of patience. I think such recognition would allow us to consider how serious a fight it is. It is as if one has to undergo a form of exorcism from patriarchal norms. This then makes me understand how activists become fatigued and overwhelmed; because it can feel as if they are fighting everything and everyone. And it never ends but we also never stop.

My reservation is also based on the observation that it seems there are gatekeepers who have a certain way of going about feminism and then seem to expect the towing of that line. This is followed by name-calling upon deviating from that line, such as the term ‘pseudo-feminists’. I find that silencing and oppressive. It doesn’t provide room for being and learning. And I would not want to find myself identifying with that.

At the same time, I feel uncomfortable with the idea that we can just decide what is and what is not feminism when it suits us. Sometimes it feels there is no common understanding or agreement of what it means. While I’m reluctant to allow one group of feminists to ‘own’ feminism, I would like a common or grounding idea of feminism to root me and others.

I am an African feminist, but tend to assert this in what I consider to be safe spaces; in other spaces you are most likely to hear me make statements such as ‘… I am inclined to feminist thinking …’ (which is the truth) or ‘… I aspire to be feminist …’ (the aspiration is linked to that idea of being knowledgeable, or well-educated).

I still feel I am becoming.

Making theory reality: living feminism in my life

I know that feminism implies a reimagined social order. Feminism means seeking gender equality in terms of access to social, financial, educational and political opportunities as well as being mindful of and active against all forms of oppression on all sectors of society. Feminism is challenging gender norms and stereotypes.

Over the years, I have also become more aware of what I say and how I behave in order to smash my own patriarchal tendencies. However, it seems there are gender norms in my life that just manage to go unchallenged and when I think about it, I can’t see a clear path out. For instance, as a black South African woman, I have cultural practices that are part of my being. In these practices, there is a clear division of gender roles in that ceremonies are led by men. In all our cultural ceremonies—giving thanks, lobola negotiations or the welcoming of a child—there is evoking of ancestors. This is always done by men who may be elders in the family. Even the opening and welcoming of family/friends and neighbours into the ceremony are done by men. Women have just as significant a role in our cultural practices, but their role is hardly recognised as valuable. Women are seen as accessories to the process.

I have not seen myself attempt to question or challenge this. I have accepted that the men in my family will lead, just as I am happy to be spared the opportunity to slaughter any livestock. It is during these times that I do the ‘walk of shame’—admitting to myself that this patriarchal norm has just made my life easier. This relief is short-lived. At times like this, it suits me to not name myself as a feminist because then I don’t have to answer questions about what behaviour I insert myself within and allow. I’m less critical of myself. Sometimes I let myself off the hook.

Feminism is my superpower

I have deep love for my feminist life. Feminism heightens my awareness to the human condition. I have developed a sharper eye and ear to a harmful status quo. I notice the formal and informal conversations that are unjust and unprogressive in my circles. Feminism has made me pay attention.

I am a quiet and introverted person and believe my strength is in writing. I am happy to be called a ‘keyboard activist’. I use my keyboard and my voice to denounce oppression when I see or hear it in my family and community spaces. The best part is that even the smallest forms of activism help the greater protection of human rights.

My feminism feels like the nurturing aspect of parenting; whereby parents become aware of their children’s different discomforts at different times and act within their means to help address those discomforts. It’s about being constantly aware of how people can be differently oppressed. I feel as if I am gaining that superpower and ability. It also seems to require patience and the ability to forgive oneself. As much as I am sharpened in my awareness, I still miss some things. That is why feminist support networks are so valuable.

Recently, my feminism has been greatly and warmly supported by the women at Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust and at the African Women’s Development Fund. There, I found an investment in my becoming a feminist leader and an enabling space was availed for my feminism to be strengthened. I left the feminist leadership coaching journey with a mind and heart well placed to further the cause in my corner.

This is, and never was, an attitude problem; this is my feminist journey. I can also proclaim, as African Feminists declared in the AWDF Feminist Charter that ‘I am a feminist, no buts and no ifs.’

~~~

- Neliswa Tshazi qualified as a social worker at UCT. You can find her at Rape Crisis supporting and empowering survivors of gender-based violence. Follow her on Twitter.

~~~

About the book

The power of structural violence is that it tries to silence us. The power of feminism is that it gives us a voice.

So much of our life experience is filtered through our bodies – norms, myths, and cultural standards continue to shape the way that we and the world feel about our bodies and how we see ourselves.

Feminism says these rules are bullshit. Our bodies can be tools to conform or a way to resist. Feminism is necessary to help us learn and unlearn things about ourselves and the world we live in. Feminism is for all of us, for every single body.

This collection take us from an examination of skin and hair, to an exploration of pleasure, sex, and safety. They explore the way our bodies change, our health, and how we become who we are. They examine the way that institutions can trap us, how we can trap ourselves, and the importance of our hearts in all of this.

About the editor

Jen Thorpe is a feminist writer and researcher based in Cape Town. Her first novel, The Peculiars (2016), was longlisted for the Etisalat Prize for Literature and the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize. Previous collections include My First Time (2012) and Feminism Is: South Africans Speak Their Truth (2018).