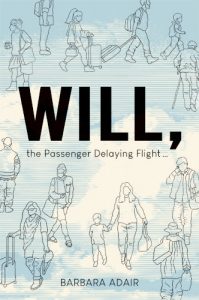

The JRB presents an excerpt from Barbara Adair’s new novel WILL, the Passenger Delaying Flight …

WILL, the Passenger Delaying Flight …

Barbara Adair

Modjaji Books, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Jean Claude is nineteen years old. He is a thief, the always to be found in an airport, or any other crowded space, pickpocket. He works for, or is employed by, a pickpocket group; some would call it a loose group of thieves, others a gang, but these terms connote something inchoate, unstructured, disorganised. In fact it is a well-organised formal organisation, in other circumstances, and should it be socially acceptable, it could have been a registered financial services company, or a hedge fund, or even a bank. The organisation is not merely a group of people; it is a corporation, with branches in all the major cities of France. The Paris group, or subsidiary, is the largest division in the corporation. They work in all the airports, stations and bus stations of the city. In each transport hub at least two, sometimes three, pickpockets work.

The group, or gang, has a hierarchy, a corporate hierarchy. There is a central structure in which there is a chairman and board of directors, they manage the entire organisation. Each division, the Paris division is no different, has a management structure and many workers. There is a divisional chairman. In Paris he is charismatic, cruel, dogmatic and educated. He always uses Voltaire’s words, Man is born free but is everywhere in chains, to motivate the pickpockets. They are, he explains, enchained by what is defined as right, and he, or the organisation, can give them the opportunity to be free, to earn money, to determine their own destiny. Who cares what is right or wrong anyway? What he does not say is that the freedom he believes in is his own, not that of others. He earns a lot of money from his pickpocket workers. He is often compared to Steve Jobs because another of his much-repeated phrases is ‘An apple a day keeps the cops away’. And the chairman eats nothing but fruit, he is a fruitarian, and he loves apples, the ripe red ones. He does not believe in killing, either another human being or animals, and so he does not encourage the use of violence among his workers.

Then there is a training officer who determines what training is required to be a successful pickpocket. To be a pickpocket is not merely to be a thief. It is a skill and requires many hours of training; how to distract a person without them being aware that this is a distraction, how to reach into a pocket without the other feeling anything, and most of all how to identify the most lucrative target and, once identified, in which pocket or bag the most valuable items are. In this group the chairman insists that all pickpockets, no matter what they say their previous experience is, must be trained from inception. As it is, most of the recruits know little or nothing at all about pickpocketing so the training officer is always busy devising new courses, assessing who needs further training or empowerment, and, of course, whether or not a person can, in fact, come up to scratch, or if he is untrainable.

There is also the financial officer, who determines what each pickpocket is paid. A pickpocket does not steal and then keep the proceeds of his efforts; all stolen goods are centralised and then either sold immediately, or kept for a period and then sold. If the goods are of no value at all, rather than return whatever it is to the lost property department of the particular transport hub from where it came, they are destroyed. There are harsh penalties for keeping things stolen to oneself. Often a wallet is taken; travellers often imagine that wherever it is they are going will have no cash available. This is especially true in the airports, and if they are American or European and are going into Africa for the first time, they do not know and cannot imagine that an African city has auto tellers in it. Africa is backward and wild; tigers walk in the streets of the cities there. (18) And jewellery. Women frequently put their valuable jewellery into the pockets of their jackets or dresses. They imagine to wear it is too dangerous, it may be stolen, or it may be detected by a wary customs official, and so they hide it. They are unaware that it is better to wear jewellery, it is less easy to steal and most customs officials cannot tell a diamond from diamanté.

Then of course there is the human resources officer. He is the one who finds the new recruits, interviews them, identifies who has potential or experience or the desired qualifications. Qualifications are particularly important. A good pickpocket is also a semiotician: he can read the signs and can quote Barthes to any unsuspecting traveller. But there is a nasty side to this position of human resources officer. Part of the job is to manage the number of pickpockets, and sometimes it is necessary to let a pickpocket go, he could be retrenched, in which case a package is paid to his loved ones, his elderly mother or his fiancée or child, and then he is relocated deep down under; or he could be dismissed for some kind of misconduct, thrown into the Seine with rocks in his pockets and his throat slit from ear to ear.

18. In fact there are no tigers in Africa, except in 2000, when the South African film maker and landowner John Varty brought several tigers to his farm in Philippolis, in the Free State, in order to start the first tiger breeding programme outside Asia. Varty made two films, Living with Tigers and Tiger Man of Africa, which have been criticised by environmentalists as being only made to boost Varty’s fading and faltering ego while taking tigers from their natural habitat. In 2012, as divine justice will have it, Varty was seriously injured by two of his tigers. He has never fully recovered from his injuries.

~~~

‘Barbara Adair is one of South Africa’s most original writers. In WILL, the Passenger Delaying Flight … her voice is comical, dark and wittily allusive. Enigmatic from beginning to end, the novel (set in an airport) never goes where one expects. The narrative is tightly woven; yet still it soars, borne aloft by its own imaginative charge and linguistic richness.’

—David Medalie, writer and Professor of English Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Pretoria

A man is travelling to Africa from Europe. And yet it is also about waiting—waiting for Africa.

Volker, a German, leaves his home in Frankfurt for Windhoek. He leaves a lover, he is leaving for a long time, and he does not have a return ticket. He does not know anything about Africa, to him it is one country, not a continent, neither does he really know where he is going to; he just knows that he wants to leave Europe.

Lufthansa, the airline that carries him stops at Charles de Gaulle airport and here he waits and waits and waits. And in the airport he observes and describes and thinks. The text is a stream of consciousness, Volker’s thoughts. Interspersed with this are stories of people he encounters in the airport; a murderer, a terrorist, a person with dwarfism, a trans woman, a porn star, a terrorist, a child trafficker, a paedophile. All are connected, with each other, with Volker and with us, the readers.

Adair’s novel is innovative in form, self-conscious and self-critical; it challenges conventional Western assumptions that all good novels have a clear story line, a good plot and fully rounded characters.

‘Adair is an accomplished writer with the ability to transport her readers into seductive and, at times, dark worlds she skilfully conjures.’

—Barbara Boswell, Professor of English University of Cape Town and author of Grace, a novel.

‘In a dystopian world that has served up an imperfect future, Adair breathes life into the limbo and emotional baggage of her characters as they travel across the world.’

—Karabo K Kgoleng, broadcaster, public speaker, writer

Modjaji Books are also republishing Barbara’s novel In Tangier We Killed the Blue Parrot, which was published in 2005 by Jacana. The book was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Fiction Award in 2005. An academic article on the book was published in the prestigious Commonwealth Journal of Literature in December 2019. The book was published in Spanish by Mariana Jorge Lozano: Baphala Ediciones in April 2020.

About the author

Barbara Adair is a writer with published experience in the following areas: fiction, both novels and short stories, travel articles, book reviews. She writes, and also works part time at the Wits University Writing Centre and in Nairobi, Kenya, consulting and assisting students in critical thinking. She previously practised as an attorney litigating on human rights issues, and thereafter taught constitutional law at Wits University. Adair is currently registered as a PhD student at the University of Pretoria.