To honour JM Coetzee’s eightieth birthday on 9 February 2020, an exhibition celebrating his life and work titled Scenes from the South is being held at the Amazwi South African Museum of Literature in Makhanda. Angelo Fick reflects on the event.

The public celebration of a deeply private individual is always paradoxical: those participating in the ritual want to show in public what they feel in private to honour the reticent, shy, figure who becomes the focus of the spectacle. In marking milestones in the lives of writers there is always tension between publicity and privacy. Writing, after all, is traditionally a solitary activity, as is reading. But to facilitate the transition from the former to the latter, some publicity is often required. Some writers have refused to participate in what are essentially side-shows in the literary enterprise—they make no public appearances, like Thomas Pynchon, or they rarely grant media interviews.

JM Coetzee has the not entirely undeserved reputation for being publicity shy. Journalists have remarked on his reticence in interviews, and in Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews (1991) he outlined the reasons for this curbed enthusiasm. While his writing has been subject to much public debate, he has shown little appetite to inhabit the role of a public intellectual that is often thrust upon writers:

‘I don’t regard myself as a public figure, a figure in the public domain. I dislike the violation of propriety, to say nothing of the violation of private space, that occurs in the typical interview.’

But when occasion necessitated, he has shown up, literally and figuratively. One thinks of his acceptance of the Nobel Prize, and his attendance at the ceremonies attached to that honour.

Days before his eightieth birthday, Coetzee flew from Australia, where he now lives, to South Africa, to attend an event celebrating him and his work. The festivities centred on ‘Scenes from the South’, an exhibition at the Amazwi South African Museum of Literature in Makhanda in the Eastern Cape. ‘Scenes from the South’ brings together material from the Harry Ransom Centre in Austin, Texas, and the Amazwi Museum (formerly the National English Literary Museum), and is curated by Kai Easton, a literary scholar of Coetzee’s work based at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, and David Attwell, a preeminent critic of Coetzee’s oeuvre based at the University of York.

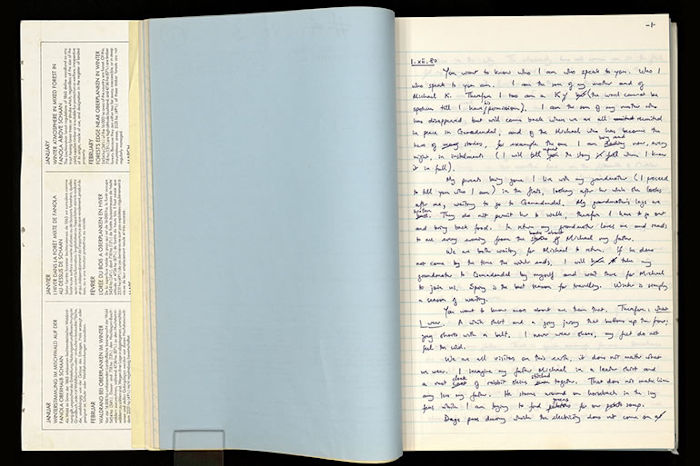

The exhibition includes various items and documents related to Coetzee’s life as a writer. There are samples from correspondence with publishers and other writers about his work and theirs. There are drafts in Coetzee’s handwriting of what would become Dusklands (1974) and Boyhood (1997). But there are also excerpts from his school notebooks, maps he drew as a child, and photographs of his family life over the decades. These provide glimpses into the life of John Coetzee, the man, who engenders the writer, JM Coetzee, through the act of writing. But they are merely glimpses. The ‘real’ John Coetzee, whatever that may be, one imagines, will not be so easily captured and displayed.

Coetzee’s energetic attendance at the two days of events marking his eightieth birthday—from the opening ceremony for ‘Scenes from the South’, which also constituted a birthday party at the Amazwi Museum on Sunday, 9 February, to the day-long symposium of writers, musicians and artists on Monday, 10 February—was admirable. In contrast to his reputation as a curmudgeon, Coetzee remained polite, interested and engaged. From the generous praise of Australian High Commissioner Gita Kamath on the first night, through the toasts and the speeches, this quiet, shy man responded gracefully, and with good humour. No signs of stress from jet lag, or flight delays, or the lack of running water in the town he had come to for the celebration.

Those who had come to celebrate John Coetzee at eighty included former students, a host of South African poets (including Ingrid de Kok, Rustum Kozain and Antjie Krog), and writers of fiction (including Siphiwo Mahala, Nthikeng Mohlele, Ivan Vladislavić and Zoë Wicomb), as well as academics who have published on Coetzee’s work, including Attwell, Easton, Derek Attridge and Carrol Clarkson. Some of these writers also contributed to the Festschrift prepared as a birthday gift for John by his partner, the academic and feminist literary critic Dorothy Driver.

A Book of Friends: In Honour of JM Coetzee on his 80th Birthday (Text Publishers 2020; reprinted by Amazwi 2020), is an eclectic selection of fiction, poetry, visual art, critical essays and reminiscences by ‘creative and intellectual figures John has had close contact with over the years’, as Driver writes. In a moving foreword to what he calls ‘a collection of writings and art by friends and colleagues in honour of John on his eightieth birthday’, Jonathan Lear links his first reading of Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980) with his initial encounter with John at the University of Chicago in the mid-nineteen-nineties, offering insight into the truth behind the public misapprehension of Coetzee as a recluse.

A Book of Friends contains several lovely contributions that allow a glimpse into how other creative artists think about their relationship with John Coetzee the man, sometimes partly because of their relationship with JM Coetzee the writer. Among the visual artworks included in the collection, most noteworthy are reproductions of a beautiful portrait of Coetzee by Adam Chang (the original work in earthy red tones, oil on canvas, measures 3.1m by 2.4m), and two works by David Coetzee, the Nobel laureate’s brother.

At the heart of the collection is David Malouf’s ‘Birthday Poem’, in which the poet, seemingly addressing the novelist being honoured,

throw[s] back

five metres of white translucent

nylon on the blue

infinities of a day, like all

the many days before it, millennial

light-years in the making.

It is a poignant tribute from one gentle soul to another. This tone is echoed in Rajend Mesthrie’s ‘Onoma and Anomie’; the renowned South African linguist praises Coetzee as ‘my first inspirational teacher of linguistics’, before embarking on an examination of naming practices among Indian South Africans in the contemporary moment. Mesthrie, who read part of the essay at the Amazwi birthday celebrations, pays the highest tribute to a venerated teacher by demonstrating his own formidable prowess as a linguist in this insightful and humorous piece.

Other pieces in A Book of Friends reflect Coetzee’s recent pursuit of literary and artistic connections in the South, between Southern Africa, Australia and Latin America—whence the title of the Amazwi exhibition, which connects Cape Town and Adelaide and Buenos Aires, among other places. Mariana Dimópulos’s ‘Puente/Brücke/Bridge’ connects with Coetzee’s trilogy of Jesus novels (The Childhood of Jesus, 2013; The Schooldays of Jesus, 2016; and The Death of Jesus, 2019) in its concern with migration (both literal and figurative), translation, and being. Shannon Burns’s ‘Where’s John?’ engages in a delightful, clever literary game with Boyhood (1997) that echoes Coetzee’s own engagements with Defoe and Dostoyevsky in Foe (1986) and The Master of Petersburg (1996) respectively.

The poet Rustum Kozain, the last writer to read on the Monday afternoon before Coetzee’s evening reading, offered a tribute to Coetzee via a compelling allegory of honour and respect as a form of anthropophagy, a deliciously ironic response to Coetzee’s own ‘Meat Country’ (1995). That Coetzee was laughing out loud during the reading was a tribute not just to Kozain’s deft humour, but also to his (Coetzee’s) staying power—not a sign of flagging from the octogenarian who had flown first east from Adelaide to Sydney in Australia, then west across the Indian Ocean to Johannesburg, and then south to Port Elizabeth, before travelling overland to Makhanda, seventy-two hours earlier. Having attended all the panels and musical tributes over two long days, Coetzee proceeded to read two chapters from The Death of Jesus to close the event.

If he had not had his fill of those who had come to Makhanda to celebrate him (and there was no sign that he did), those who came to celebrate the Nobel Laureate at eighty ought to have had their fill of ‘roasted Coetzee’, the deeply private man who had given so generously of his time and energy.

- Angelo Fick is a Director of Research at the Auwal Socio-economic Research Institute (ASRI) in Johannesburg. He taught across various disciplines in the humanities and sciences at universities in South Africa and Europe for two decades, before a brief stint as a news analyst in the broadcast industry. His work has appeared in the Mail & Guardian, The Funambulist Magazine, the Journal of Commonwealth Literature and English in Africa.