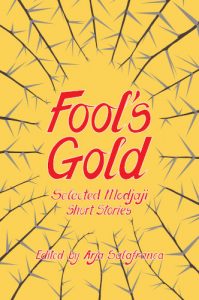

The JRB presents an excerpt from Fool’s Gold: Selected Modjaji Short Stories, edited by Arja Salafranca.

Since its inception in 2007, Modjaji Books has published ten short story collections and two anthologies, The Bed Book of Short Stories in 2010 and Stray in 2015.

Fool’s Gold is a collected volume, containing one story each from the ten individual collections and a handful from the two anthologies, showcasing a variety of styles and voices.

Fool’s Gold: Selected Modjaji Short Stories

Edited by Arja Salafranca

Modjaji Books, 2019

‘A snapshot of lives, and without the lengthy commitment of a novel, some say a short story is ideal for our busy, digital-led lives,’ Arja Salafranca writes in the collection’s Foreword. ‘They are coming into their own, having faded in popularity at times, this year alone [2019] has seen a plethora of individual story collections being published, which is good news for the form.

‘I was both excited and honoured to be chosen to edit this selection of Modjaji fiction,’ Salafranca continues. ‘While I have always loved the sweep of reading novels, the short story offers something else entirely. Within a few pages a writer can evoke a world, a moment or a bright epiphany, that lingers and reverberates long after the initial reading. A writer doesn’t need a novel to tell a story, or create a powerful impact in their story telling.’

Salafranca calls our featured story a ‘haunting and achingly poignant story of a young woman looking for something less than love with the army guys who pass through the Free State town she lives in’.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

The Outsider

By Isabella Morris

In the feeble light of the bathroom Lorinda smeared the last blob of Coral Shimmer onto her lips and squeezed them together to spread the lipstick. She tiptoed down the narrow passage, so that the clickety-clack of her high heels didn’t alert Pa, but when she crossed into the kitchen Pa was already sitting in his wheelchair next to the fire, the Raceform folded on the table next to him.

‘You look fancy for a girl who’s just going to the TAB,’ he said. Lorinda ignored him and picked up a piece of cold toast; she snapped off the crusts, spiralled honey onto the middle and handed it to Pa, then she leaned over and kissed him on the forehead, holding her breath against the suffocating smell rising from his unwashed hair.

While Pa sucked at the sticky toast, Lorinda examined the betting forms he had filled in. ‘Rolling Thunder, he’s an outsider Pa but I’ve also got a good feeling about his chances,’ she said and placed her father’s bets in her handbag. Then she knelt down on the cold stone floor and removed a bottle of Klipdrift from the bottom shelf of the kitchen dresser. Pa eyed the half-jack of brandy and patted her arm as she placed the bottle on the table. ‘You’re okay for a girl you know,’ he said.

She unlatched the top half of the stable-door and stared up at the sky; the slow rolling clouds promised a spectacular storm. The fox terrier scratched against the door and Lorinda went outside and filled its bowl with fresh water from the tap that dripped into a patch of mint.

‘Hey Bella, look after Pa, hey,’ she said as she broke into a run towards Pa’s bakkie, ignoring the animal’s watery eyes.

The hectares of fields on either side of the highway were monotonous khaki blankets overhung with gravid clouds. Lorinda flicked the windscreen wiper lever when the first drops of rain splashed onto the windscreen, and reduced her speed to a cautious ten kilometres lower than the speed limit. She drove up and over the swells of the road until she saw the picnic area and pulled across from left to right; she drove on the opposite shoulder of the quiet road until she reached the desolate cluster of cement picnic furniture and a rusted garbage barrel, dry grass sprouting from the holes in the bottom.

She preferred to park the bakkie so that she was facing oncoming traffic, that way nobody could surprise her from behind. She took off her shoes and hobbled over the gravel, wincing at the pressure of the sharp stones underfoot. She unlocked the small doors of the bakkie, climbed into the back and knelt on the flatbed, its ridged metal bruising her knees. She unrolled the mattress with a deft movement and then she spread out the white cotton sheets that smelled of Spring Blossom fabric softener. She closed the flimsy yellow curtains she had made at sewing classes in Bethlehem the previous year, courtesy of one of Pa’s gambling windfalls. When she was satisfied with the cosy bedroom she had created, she sprayed one squirt of Panache into the air then quickly jumped down from the back of the bakkie and closed the doors.

As she drove into town, she kept an eye on the dashboard clock, hoping that the TAB wouldn’t be overcrowded; it was the end of the month and punters were usually over hopeful when their pockets were full.

Lorinda parked in a side street and pulled on her raincoat. The TAB was busy; punters pencilled in their choices for jackpots and place accumulators and tri-fectas as they stood in a queue that meandered drunkenly around the block. Lorinda flicked open her umbrella. It wasn’t necessary; the pavement was sheltered by an overhang, but the umbrella kept a circle of space around her. She was careful to keep her eyes downcast so that she didn’t have to acknowledge anyone she might recognise from church or the Vroue Federasie.

Mr Kletz held out both his hands when Lorinda reached the counter; she handed the bets over to him and watched as he fed them into the machine. He kept his left hand outstretched, but Lorinda waited until the machine had finished grinding and only when she saw the red figures blinking on the small screen did she part with the money, mentally calculating her change while the machine spat out the printed tickets.

‘Pretty Tart,’ Mr Kletz said.

‘I beg your pardon?’ Lorinda asked; her armpits prickled.

‘That Rolling Thunder’s an outsider; a safer bet would have been Pretty Tart,’ he said, but his impatient eyes had already flicked past Lorinda, and his hands were reaching to take the next punter’s bets.

Back in the familiar confines of the bakkie, Lorinda accelerated, freeing herself from the town with its narrow streets and inquiring eyes. Lightning momentarily brightened the overcast sky and Lorinda wondered how many hitchhikers were likely to be thumbing a ride in such inclement weather. She drove the bakkie to the stony ridge that formed the southern boundary of the blind Widow Verster’s farm and waited there. She had to turn on the ignition every few minutes so that the windscreen wiper could clear the raindrops. Through Pa’s old racing binoculars she could see the main road and the place where the swinging Ry Veilig / Ride Safe sign caught the light as it swayed in the storm. She’d easily see any army guys who arrived there hoping to hitch a ride to the station.

The guy who had been dropped off was tall, so tall that Lorinda almost drove past him. She couldn’t imagine his long legs finding a comfortable position in the confinement of the cab. Instead, she slowed onto the newly tarred shoulder of the road and stopped. The Ride Safe sign cast a long shadow across the bonnet. He bent down and looked at her through the window, a cautious smile; she flipped the lock.

All night long the guys had teased him about the toothless farmers who liked to pick up army guys and give them blowjobs. He had considered walking all the way to Bethlehem, but soon changed his mind when the Bedford dropped him off on the tarred road and through the light rainfall he saw nothing but a basket weave of farmlands stretching into the horizon. The driver was no farmer; she had a tight white smile and a short skirt.

‘Where you going?’ She asked as he squeezed himself into the bakkie.

‘To Joburg.’

‘How long is your leave?’

‘Three days, I’ve got to be back on Tuesday.’

‘Are you going to hitch or take the train?’

‘Haven’t thought that far ahead, I just wanted to get the fuck out of that shithole—sorry—for swearing.’

She couldn’t decide if he was handsome in an ugly way, or ugly in a handsome way; it was hard to gauge the level of attractiveness of these bald army guys; he had bluish lips and a skein of scars, but his mouth looked kind; she would bet money that his nipples were brown instead of pink.

‘Do you want to drive?’ she asked him. If she spoke in simple sentences, she would manage the English.

He hadn’t been behind the wheel of a car for ages, but before he could respond she reached her left hand across his lap and lifted herself over him, making sure that her bottom grazed his crotch. He could smell the apple scent of her shampoo, feel the honey heaviness of her hair against his cheek; he slid across, the steering wheel was warm where she had held it. She sat with her back against the door and tucked her right leg under her butt so that a small triangular window opened at her thighs and skirt hem and gave him a seductive view of her crotch. He started the bakkie and pulled onto the road without even looking in the mirror. It had been a long time since he had driven a car; it was even longer since he’d had screwed anyone.

As they drove towards Bethlehem the wind cracked against the bakkie, rapid as an R1 round. Platoons of poplars, match-skinny, stood to attention on the roadside.

She said, ‘Are you married?’

He shook his head.

‘—verloof, um, engaged?’

Another head shake.

‘—gay?’

He laughed, so she did too.

She waited for him to ask her something; she wanted to tell him about herself. The other guys always asked—where she lived, who she lived with, why she wasn’t married—a looker like her. But he wasn’t going to ask her any of that, she could just tell from the way his eyes didn’t rise quite high enough to meet hers. His disinterest left her with the same cheated feeling she got when she bought hertzoggies that had been baked with margarine instead of butter.

‘I don’t care if you are married or you a moffie you know—it doesn’t matter to me.’

He kept his eyes on the road. Farmhouses peeped shyly from between tree-breaks, or turned their backs to the winds of the open plains.

‘Are you hungry?’

He glanced across the cab as she opened the cubbyhole, shrugged his shoulders.

‘Pepper-steak pie or Simba crisps—salt and vinegar flavour?’ she asked.

The pie, I’ll have the pie thanks.’

She slid the pie halfway out of the packet and then twisted the paper so that he could eat it without a crumb-fallout in his lap; Pa said a girl had to be clever no matter what, but it was Ma who used to say a way to a man’s heart was through his stomach.

He ate the pie, using his knees to help him steer. The distance marker indicated that Bethlehem was 7km away; he kept his eyes on the road.

She leaned over and ran her fingers across the black letters of his nametag: YFOUCHARD. No space between the initials and his surname, but she had no difficulty identifying which was which.

‘Yakob? Yitzhak? Yonatan?—Jislaaik! Are you Jewish?’

He shook his head and made the sign of the cross.

She rolled her eyes, there was only one thing Pa hated more than Jews, and that was Catholics.

‘Yvan! That’s it, hey? You’re a Russian, or from Poland!’ She bounced up and down on the narrow seat and clapped her hands.

He wasn’t going to tell her his name was Yves; he despised the ignorance about his French name.

She pouted. ‘You’re not very friendly are you; especially considering I’ve just given you a lift,’ she said and lifted her left leg onto the dashboard; Maybe he didn’t have a lot to say, but she saw him look, his dark-lidded eyes unsettled her.

‘You didn’t just happen to be on the road back there, did you?’ he said, slowing the car down.

She chewed at a hangnail.

‘What were you doing back there, hanging around in the middle of nowhere?’ he insisted.

In the early days of her courier service she had prepared excuses—like folded love-letters tucked into her mind and ready to go. ‘I’ve got to check on one of our sick lambs at the vet in town,’ or ‘I got lost looking for a farm that has a foal for sale.’ But army guys didn’t seem to care, they were just grateful for the lift. She pretended not to understand Yves’s question, instead she leaned forward, touched the blue shadow on his chin where the black stubble would break through by nightfall.

‘I pick up troepies and I fuck them. Please tell me you’ve just come back from the Caprivi. Please, please, please! I haven’t fucked anyone who’s been to the border yet,’ she said.

He ignored her irritating bouncing on the seat, her shining eyes. He pretended not to understand her desperation for a troepie who’d been to the border. His bunk-mate Venter had slapped his thighs with frustration when Yves told him he was heading home for the weekend pass. ‘Ag, jirre, you lucky fucking poes! You know how chicks dig ou’s from the border; I don’t know what it is. It’s like they think you got a dick like a rocket or something, fuck man!’

She edged closer to him and one by one she removed his left hand fingers from the steering wheel, she brought his hand over to her and slid his fingers into the soft place beneath her panties.

He stared at her small pointy chin, her fine narrow nose, but her eyes were closed, her head dropped back so that all he could see was taptapping in the vein that crossed the hollow of her throat.

‘You can stop about two kilometres before town. There’s a group of blue gums and a road that goes nowhere,’ she said.

He didn’t have to move his fingers; she manipulated her pelvis so that he could feel her contracting against them. It was difficult to steer and change gears with his right hand and he eventually screeched up the muddy road in first gear; she leaned over and cut the engine, his fingers twisting inside her as she did so. Then she lifted herself, disconnecting. She slid open the rectangular window hatch behind her in the cab and wriggled into the back of the bakkie. He watched her pale legs disappear. He sat in the cab for a long time listening to the wind rustling the dry leaves of the blue gums. He glanced at the window and knew he could not manoeuvre himself through the same narrow space that the girl had. He stepped out of the cab and walked around to the back. As soon as he opened the squeaky doors he smelled the fresh linen; he sat on the flatbed and unlaced his muddy boots.

She knew that if she wanted more than a wham-bam-thank-you-mam quickie she’d better get him into the mood to play for a little bit longer. Instead of stripping down completely she wore a white lace bra and panties. Her brother Rudolf’s Scope said that apricot or pink underwear wasn’t as big a turn-on for men as women believed it to be; black was provocative and so was red, but white was the colour that really got men’s guns loaded. White was virginal, pure, and every man wanted to think he was the first, even if he knew he wasn’t. By the look on his face, he was definitely pleased with her lingerie.

‘My name is …’ she began, but he clamped his hand over her smile.

‘It’s just a fuck,’ he said.

She was good at releasing khaki buttons from stiff buttonholes with her teeth; loved rolling her tongue across broad chests, but he kept her on her back by fastening her left arm behind her head in a strong grip. He was on top of her. She swallowed the lump in her throat, she had never fucked anyone whose name she didn’t know. His feet were freezing. Her nipples tightened. She touched herself with her right hand and drew her fingers up to his lips but he turned away. She felt shame searing her cheeks.

When he was finished, he rolled off her and lay panting with his eyes closed. She edged closer until her face was against his shoulder; she was right, his nipples were brown with the smallest curls of dark hair around them. She could have leaned across him right then and nibbled one, but instead she closed her eyes to stop the tears. He used his feet to find his pants. He lit a Chesterfield in the back of the bakkie, blowing smoke rings so perfect she couldn’t resist stabbing her finger into them. He offered her a drag but she shook her head even though she smoked a box of twenty a day. When her breath was steady enough to reassure her that she wasn’t going to cry, she sat up and opened one of the small curtains. The wheat fields all around whispered a sigh of sameness that resonated so deeply within her that she knew she could not go home.

‘Come with me to the cheese festival,’ she said.

He kept his eyes on the ceiling; made no acknowledgement of her suggestion. Though he thought then of his parents … He glanced at his watch—quarter to twelve, Saturday. They would be standing in Sandro’s Deli, arguing over whether to buy the Emmentaler or the Edam. They would hand over the money with a grimace of reluctance because they didn’t like Sandro, the Italian owner, but where else in Johannesburg were discerning French ex-pats supposed to buy quality food? Grandpère Fouchard would be in the family’s pale blue Renault tapping his knees and watching the parking meter.

‘Do you like it here?’ she asked.

He shrugged, looked at her.

‘How long have you been at this camp?’

He looked away again, drew on his cigarette.

‘Give me a drag of your smoke.’ She held out her fingers but he narrowed his eyes and drew on the cigarette, allowing the hot edge to run down the cigarette until it almost reached the filter, and then he blew out the thinnest reed of white smoke. ‘Please come with me to the festival,’ she said. She kept her eyes on her panties as she untwisted them and pulled them over her calves; they caught slightly at the damp part at the top of her thighs.

He stood next to the bakkie in his underpants and ground out his cigarette next to the rear wheel. When Maman and Papa finished their shopping they would drive Grandpère to Alliance Française where he played boules every Saturday afternoon with other old men who smelled of unwashed wool, and onions and red wine.

He took a slash against the blue gum tree. His brother Gregoire, or Greg as his friends called him, would be watching the 1st XI at the school field, and in between changeovers and innings, Gregoire would tell everyone how his brother from the border was coming home for the weekend. Surrounded by his team-mates, Greg would promise them a story on Monday—a war story, a hero’s story; a story that Yves couldn’t produce. Yves pulled up his zip with a violent yank and stalked towards Lorinda. ‘Where would we stay?’

His question startled her. She hadn’t expected an answer and was lost in her hopes that Pa’s bets on Random Excuse were going to pay off. She watched YFOUCHARD pull on his khaki fatigues. She waved her hand around the bakkie, ‘Ag, ons kan –’

He glanced at her sharply.

‘We’ll book into a caravan park; it’s cheap,’ she said and her hands moved quickly, snapping her lacy bra behind her, pulling on the tube of skirt and a soft white T-shirt; she didn’t want him to change his mind; she tossed him the keys. ‘Come, let’s go.’

She turned on the radio and leaned closer to the dashboard so that she could hear the commentator. ‘And it’s Leaping Star and Pretty Tart. Rolling Thunder’s coming up on the inside, with two hundred metres to go it’s anyone’s race. Habib’s encouraging Leaping Star but it’s Rolling Thunder making the home straight his own. Pretty Tart’s not prepared to let Rolling Thunder take the race, she’s holding the pace. With fifty metres to go it’s Pretty Tart and Rolling Thunder. Leaping Star will have to be content with a third. There’s nothing between Pretty Tart and the outsider Rolling Thunder but as they cross the finish line it’s—’

He leaned across her and turned down the volume.

She turned to face him, her face twisted with frustration. What would she tell Pa? But he didn’t notice, he was looking in the rear-view mirror, reversing the bakkie. When they pulled onto the main road he looked at her and asked, ‘What’s your name?’

~~~

- Isabella Morris is a teacher, award-winning writer, ghostwriter, and editor. She is the author of four full-length books, and several short stories that have been translated and appeared in numerous publications, locally and internationally. She is currently working on her PhD in creative writing (UKZN) focusing on decolonised trauma theory, and lives in Alexandria, Egypt where she teaches English.