As part of our January Conversation Issue, author and Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile is in conversation with Jason Reynolds, the New York Times bestselling author whose titles include All American Boys, the Track series, Long Way Down, For Everyone, Miles Morales: Spiderman and, most recently, Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks. On Monday, Reynolds was named the US Library of Congress’ National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. He has previously won the Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work for Youth/Teen, the Kirkus Prize, and the Schneider Family Book Award.

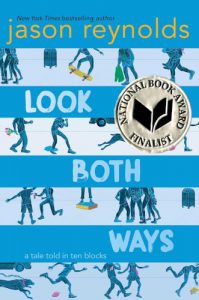

Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks

Jason Reynolds

Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books, 2019

Finalist for a National Book Award

Tony Eprile: In a recent panel on Toni Morrison’s legacy, you used the phrase, ‘resisting the literary gaze’. Can you talk a little about this?

Jason Reynolds: I think with all the arts, there’s always been hierarchies. If we think back to jazz, the way that Louis Armstrong talked about Miles. He thought it was terrible, he thought Miles was ruining jazz, he thought it was less than, that the music was irresponsible and undisciplined. It’s the same way with the visual arts: ‘Is Pop Art art?’ With children’s literature—because literature is one of the oldest art forms, it tends to have a bit of an elitist tinge to it. And because of the categories created, categories that did not always exist in the house of literature —like ‘young adult’, and ‘middle grade’—but with the making of said rooms, we now can create hierarchy again. People think of young people’s literature as less than but what they really think is that young people are less than, that children are unsophisticated and uncomplicated and that they lack emotional depth. And that’s the real travesty. When I’m working on my projects, I always have to push the nagging feeling that I have to perform for people who like ‘capital L Literature’. I know my focus, I know what I’m doing and the skill it takes, but I still have to push away the murmurs: ‘Is this real literature?’

When you think about the books that people always quote, the books that made them, it’s always books like To Kill a Mockingbird. Well, the first time you read that, you were in the seventh grade. The first time you read Charlotte’s Web, yeah, you were in the fifth grade. The first time you read A Wrinkle in Time … What do people think these books are? These books are children’s books, or they were marketed toward children, and now they’re looked at as classics.

Walter Dean Myers was looked at among his peers as writing kids books, and people were always asking him, ‘When are you going to write real literature?’ And I just think it’s really arrogant, as if what is being written for adults is better, as if there’s not an equal amount of bumf on all sides. There’s as much bad literature for adults as there is for kids. There are as many underdeveloped plot lines and clichéd characters and the same pitfalls that we get criticised for exist in adult literature at the same rate. Jerry Saltz, the main art critic for New York magazine, said that eighty-five per cent of all art is bad and that it’s always been that way. You might say that art today is not like the Renaissance, but that’s because there’s no document of bad art in the Renaissance. Eighty-five per cent of that was bad shit, too. I want to be held to the same standard when it comes to integrity, but when it comes to that I’ve got to be given a shot, and what happens with the capital L crowd is they don’t give us the shot.

Tony Eprile: One problem is that the language you grew up with is not the language of New York publishing. Can you talk about how that language feeds you when you go back to the neighbourhood you grew up in?

Jason Reynolds: I think that language is validating. At the end of the day, language is the cornerstone of culture. So to put that language on the page is to put that culture on the page. There’s a quote from Hitchcock that I love: ‘As far as I’m concerned, a face is not a face until I put light on it.’ Right? And it’s almost like saying I get to crystallise, I get to immortalise this culture and moments in this culture through language, through my neighbourhood language and my familial language. That means something to me, and it’s one of the most valuable things I do, that I own, and that’s made space for me.

Tony Eprile: In your latest book, Look Both Ways, you take something super ordinary that kids do every day and give us all the different voices of these kids and the voice of that one community.

Jason Reynolds: I believe that comedians are the master magicians. The best of them take the mundane—the thing that everybody knows, like the grocery store or kids or time in the bathroom, anything—and turn it on its head or explore it from a different angle or knock it to the left just a little. And so I owe you the challenge of taking something as simple as a walk home from school and figuring out how to make that feel like magic. I have a lot of respect for my friends who write fantasy novels, but what they’re doing is creating a world of magic and what I’m trying to do is show the magic that exists in the world.

I think about the places that offer magic the most, the places I run to for refuge. And when I think about the house I grew up in, about sitting at my mother’s kitchen table, it feels like a spaceship. It feels like stepping into a chamber that is safe and protective, comfortable and comforting. The table I grew up with is long gone, there have been two or three since then, and yet it still feels like stepping into a spaceship. And that alone is a story. How do you tell the story about normalcy, about a space in the house and how that space can change and change and change but the energy of that space never changes? Things are stained and painted into the walls of that house, and that’s what I’d like to explore.

Tony Eprile: The real world surrounds kids all the time and sometimes it’s dangerous, kids are being mean to each other, there’s violence, people are getting sick, but their imaginations are also going all the time.

Jason Reynolds: Isn’t that the beauty of it all? The walk home is incredible because it’s the only time of the day that young people aren’t supervised. So, in the midst of that freedom, that autonomy, they have the freedom to explore their environment, they have the freedom to let themselves roam emotionally and mentally and really let themselves get out there. It’s the greatest gift that children have, to use their imaginations. It’s the very thing that the world and adults and school work doubletime to kill. We don’t talk about it that way because it puts us on the hook. But it’s true that we’re literally educating them out of their imaginations, we’re disciplining them out of their imaginations, we’re scaring them out of their imaginations, we’re disappointing them out of their imaginations. It’s been happening for a very long time. A kid wants to do something that may seem a little strange, and the adults say that’s not what you do. Teachers say that the sun can’t be green, but in my world it is. When I’m telling my stories, especially about kids that age, around eleven or twelve, I want to show a lot of them to be far out, and if they can’t be far out, I want to show what is happening around them that’s restricting it, which puts the onus back on us.

They’re born with a wealth of imagination. Think about it: if you’re discovering the world for the first time, the magic is all there. My job is to preserve it through literature. Even for myself; it’s also for me. [laughs]

Tony Eprile: You show a lot of sympathy for the kids that adults think of as bad kids.

Jason Reynolds: When you think of all our heroes, especially the artists who make things, actors or comedians—well, actors are really annoying. They were the annoying kids who were always full of energy, always on stage, maybe a little awkward during their middle and high school years. But that performance element is who they are, and sometimes that bristles in the classroom setting. Like that scene in Look Both Ways where the young lady gets to get up and do her comedy act, that’s Martin Lawrence—that was his story when he was in high school. That teacher who said, ‘If you can keep quiet, I’ll let you get up the last five minutes and present your act.’

I also think there are kids who are dealing with life stuff, they’re different and not different. They’re equipped with a different skill set very early. Unfortunately, it may be coming through trauma, it may be coming through being forced to be older than they should be. They have a toolkit a little deeper because it’s had to be. Kids who grow up in New York City, by the time they’re ten or twelve years old they can navigate space in a very different way, they’re hyper-aware of their environment because they have to be. I want to make sure I show those kids not as broken, but as brilliant.

Tony Eprile: You have just been named the Children’s Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the Library of Congress, which is quite an honour. What are your plans for this position?

Jason Reynolds: This gives me a portfolio and a platform to do what I want. We all know what’s tweetable, what’s the right thing to say. We sometimes expose ourselves and our biases, because everybody says they love kids, but what they mean is they love kids in inner cities, or well-behaved suburban kids, or they love white kids. I love children, all of them. And so what I’m doing with my platform is—I’m going to small-town, rural America, the places where writers never go. Because it’s not sexy, it’s not comfortable. When it comes to the matter of children, there’s not enough space for your comfort. Because whatever you think of where these young people live, or who these young people grow up around, who their families might be, they’re still children. And they’re still ours. They’re still the children who are going to inherit this country and our world, and they deserve a fair swing no matter where they live.

I’ve been through Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Kentucky, the parts of Illinois that are not Chicago. And you go through these places, and you realise when you start talking to the kids that they’re all the same. They’re the same as the kids in China, or in Germany. They all laugh at the same jokes. Because of the internet they wear the same clothes. And how dare we erase the kids who live in places that make us uncomfortable and pretend they don’t exist so we can feel better about our own positions. I can’t live my life knowing that my kids are going to blame their peers for not knowing what my generation never gave them. This is future work. So if it makes me a little uncomfortable today or puts me in the hot seat, that’s okay. I’ve already been through it. I’ve seen the hate, I’ve seen protests, I’ve had my books banned, I’ve been through all of that. But so what? I’d rather go through it now if it means that some kid in that community sees the world as bigger than his hometown and sees that his hometown is special because it’s his hometown or her hometown.

Tony Eprile: You get a lot back from these kids, too.

Jason Reynolds: Absolutely. It should be reciprocal. There are things that I’ve learned from them. Right now we’re in the midst of another sexual revolution, and as people continue to evolve gender-wise, I’ve learned the most about it from young people. The lexicon, the language about it, I’ve learned from fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds. What a gift! And in those moments, I have to humble myself and perceive there’s a lot I don’t know. If I don’t listen, I stand a chance to hurt a lot of them. It’s a very simple thing: like a kid saying I identify as ‘she’ and, noticing my pushback, says ‘This is a very simple conversation. I’d like you to call me what I’d like you to call me.’ Why is this a debate? I’d like you to refer to me as I’d like you to refer to me. In this moment, if I love you like I say I do, I’m going to learn … from you.

Tony Eprile: What would you say to your younger self?

Jason Reynolds: I’d probably tell my sixteen-year-old self, ‘Thanks, man! Because the only reason I’ve gotten this far is I’ve done everything I can to hold onto you. You were the one who got it right! You were the one who knew that the world was actually eatable, right? There was nothing to be afraid of, that the world didn’t have to eat you. You could eat it.’ I knew that at sixteen. It was at twenty-six that I got scared. But at sixteen I was like, ‘Fuck it, I can do what I want.’ That arrogance is a healthy arrogance. Yes, it will lead to you being smacked down a few times. That will make you tougher, but the sheer gumption that these kids feel, that ‘we can change all of this, we can shift the whole system’. I’ve heard kids say, ‘When I get older, I’m going to tear down capitalism.’ We’ve heard this before, but I’m not going to put it past you. Maybe! You hold onto that, no matter what I think about it.

Most of what we criticise teenagers for is being who they are, for being teenagers. And the biggest thing we criticise them for is being too sensitive, as if that has ever been a bad thing. ‘They’re snowflakes.’ As if it’s a good thing to criticise a generation because they’re too empathetic.

Tony Eprile: It’s interesting that the way you reach young people and show they’re being heard is through books. A lot of what you’re doing is getting them to recognise that books matter.

Jason Reynolds: Books matter. I’m careful about what I want them to know. I want them to know that books matter, that stories matter. This is it. At the core of our humanity, the glue to this thing, are these stories. Our stories, collectively. I choose books, only because I believe that books are archivable and books can last forever. They aren’t ephemeral. They don’t dissipate. I also love music, but it can be vaporous. Literature can basically serve as concordance, you can go back, and back, and check it again. And you can relive it in different ways, you can read the same book every ten years and it’s different. Toni Morrison’s Beloved is a book I’ve had to grow into. I had to try it a few times before I was able to settle into it.

Books are important because they teach us a soft skill that comes from reading habits. If you can read a book, what you’re also learning on the back end is how to manage relationships. Not just because of what’s in a book but because of what it takes to read a book. We’re talking time—you’re blocking out time—we’re talking about concentration, we’re talking about listening, because in order to comprehend you’re going to have to let the words enter, sit, be synthesised, all of this. You’re going to have to be disciplined, and you’re going to have to be patient. This is what it will take for you to hold a job; this is what it will take for you to manage relationships, friendships, passions. This is human skill. I don’t give a shit what you’re reading. I don’t buy the idea that every kid has to read fiction. Most of my peers and friends at forty or fifty, especially men, are reading non-fiction. What about that? My uncle read the newspaper only, but he read it every day. We get hung up on what they have to read.

Tony Eprile: I encourage my son to read what he wants to read, but not the screen. Just read something.

Jason Reynolds: Read something. It’s like any other muscle, your brain needs this exercise. It will change the way you navigate the world around you.

Tony Eprile: What’s your next book that’s coming out?

Jason Reynolds: This book coming out in March. It’s a collaboration with Dr Ibram Kendi. He wrote Stamped from the Beginning, won the National Book Award. It was supposed to be the definitive history of race in America from 1400 to the present. An academic tome, this book has shifted the way we talk about anti-racism. It’s a breath of fresh air, probably the most important book about race written in the twenty-first century, alongside Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy and Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. We did a collaboration, a version for young people, but really a version that’s available for everybody who’s not a scholar, who doesn’t want to read eight-hundred pages. It’s called Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You. It’s my version of that book, I rewrote the whole book. To write a book like that, one that’s going to work for kids, or for a fifteen-year-old, or my mother who’s seventy-five years old, I had to think about what’s missing when it comes to academia or the way that we teach things. For kids, they’ve never read a book about history that was written for them, actually written with them in mind. It reads like a novel, at a certain clip, you can read the whole book in two hours and all the information is there. I’m really proud of it. It will probably be the most important thing I contribute to the literary landscape. I use the same mechanisms I use in novels to keep people engaged. I’m gonna think about voice, I’m thinking about pace, all these things as a way to keep you engaged, because I need you to stay with me, because this conversation is far too important.

Tony Eprile: This book and All American Boys are the ones where you most directly address race. Of course, in the others, it’s always there.

Jason Reynolds: It’s always there, even if I’m less direct in the other books. I’m a black man. I’ve lived my whole life as a black man, and therefore I don’t intellectualise my blackness. I don’t see it like that. I don’t live a life of events, it’s more a through line. It shows itself daily in all the subtle ways, so it isn’t some sort of burden that weighs heavily on my life. It’s just a stick in my craw that’s always there. But that doesn’t stop me from moving, and laughing, and singing. I just know what lurks in the bushes, that’s all. And that’s how I write the stories.

Tony Eprile: To return briefly to language, in South Africa we grow up with multiple languages. Here, in many parts of the country, it’s more like people grow up with multiple Englishes.

Jason Reynolds: We do. One of the biggest issues is we don’t grow up with multiple languages, that we aren’t bi- or trilingual, unfortunately. But we do have multiple iterations of English, multiple dialects, and depending on who you are or where you’re from, the ability to speak said dialects is a matter of life or death, a matter of marginalisation of opportunity, this is the way we’ve all been raised or trained. The fear is that in order to be able to succeed, there’s a particular English that you have to speak. There’s a standardising of the human that I think is unfair and unrealistic, and really harmful because it forces you to dismiss and decline and to make small that which is inherently yours. I know that really bothers me. On the flip side, it’s really difficult to escape it. Assimilation in this country is inherently racist in and of itself, but when it comes time to feed your children, things get funky. You got to do what you got to do. What we’re pushing back against these days is that very thing.

I think about Ryan Coogler, who did Black Panther and all those movies. This is a dude from Oakland, and when he speaks, he speaks like a dude from Oakland. He speaks like a kid who grew up in the hood, who has his own dialect, and he is who he is. He’s also great, that it does not matter. How you going to push him away when what he’s making is leaps and bounds ahead of all the other people, despite the way that he presents and speaks? Who cares? It’s important that other kids in East Oakland, and kids in Brooklyn, and DC, and Chicago, see him and say, ‘Look. He talk like me. He speaks like me, and he on TV. And he’s doing his thing.’

I shouldn’t have to continue to code-switch just because someone in the audience came not to hear Jason Reynolds but the representation of Jason Reynolds. As if there’s this other part of me that I’m supposed to turn on to show reverence for some person who’s supposed to have some sort of authority over me, as if the way I speak is automatically irreverent. But no, it isn’t. It’s just who I am. And if you respect me, you allow me to be me at all times. And that’s really part of my mission. Be yourself. Just be great. Be yourself, even if it makes people uncomfortable. Their discomfort for a few minutes ain’t got nothing to do with my discomfort for a lifetime.

Tony Eprile: Sometimes we don’t act like ourselves because we just want to be accepted.

Jason Reynolds: As I grow older, I realise—what does it matter if everyone likes me but me? At the end of the day, I just want to like myself, and if I love myself enough, the people don’t matter and the people who do like me matter the most. That’s it. Nikki Giovanni told me one time, when I asked her if she had any regrets in life. She said, ‘I have one big one.’ I said, what’s that? And she said, ‘I spent fifty years of my life hating people that couldn’t care less about my existence, when I should have spent that time loving the people who loved me.’

That’s it. That’s my mantra. That’s my life.

- Tony Eprile is the author, most recently, of the novel The Persistence of Memory, which won the Koret Foundation’s Jewish Book Award. His latest story is ‘The Island’, published in The American Scholar magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

What a great conversation, thank you for introducing me to Jason Reynolds!