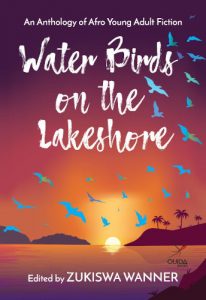

In the October issue of The JRB, we present three new short stories from the Goethe-Institut Afro Young Adult anthology, Water Birds on the Lake Shore: An Anthology of African Young Adult Fiction.

Water Birds on the Lake Shore: An Anthology of African Young Adult Fiction

Edited by Zukiswa Wanner

Ouida Books, 2019

Read the excerpt:

~~~

The Hunter

By CJ Enemuo

The grounds were wet. I’d hoped the unexpected afternoon rains would put a dampener on tonight’s hunt. But here we were, sidestepping murky puddles. Fairy-winged insects flourished in the wet aftermath, swarming to the feeble glow of our penlights.

‘Idiot, point to the ground.’ Amaha’s scowl stung more than his words. He was ahead, the length of his staff aligned to his right side. With his left side leading, he moved in robotic short steps, heels landing first onto the wet soil. His black wrap top and black wide-leg bottoms made him look like some kind of African Ninja. I’d asked for a similar outfit but was reminded that I was only here to observe.

I shuddered at the thought of the forest we were treading in, its dark history. It felt rather surreal until something quite real crawled over my foot. I cursed, my arms and legs flailing. A snake, I feared. On second thoughts, I hoped it was a snake. Considering what we were out hunting, snakes were a lot less petrifying.

Amaha shot me a glassy stare. Ms Leti remained unshaken. She was the third in our trio—unlike Amaha in many ways, including a respectable age and height difference. She moved in a crouched posture, making long strides from side to side. Wrapped tightly round her waist was an animal skin band with small open pouches around it. Each pouch held a small canister of some kind.

For the past three days, Ms Leti had been my hunting coach. For someone who looked over forty, her valour easily rivalled a male counterpart half that age.

Stay alert, always. Her number one hunter’s rule appeared to be my number one fail on my first mission. I’d affixed my wary eyes to the ground for any more unexpected creepy crawlies, and missed when Ms Leti’s hand shot up—her signal to halt. I crashed into Amaha’s right side, narrowly missing the serrated edge of his staff.

‘This boy will get us in trouble.’ Amaha’s nostrils flared like sheets on a clothing line.

We immediately pocketed our penlights and crouched behind a grove of multi-stem trees with pine-like leaves sprouting from close to their roots. Mrs. Leti put a finger to her lips, then pointed ahead to where the trees parted into a small turf with a burning flame at the centre.

‘The fire?’ I asked, not exactly sure what we were supposed to be looking at. Ms Leti’s forefinger nudged my chin a little to the side and that’s when I saw it—a dark figure lurking behind the flames. I cowered further down as I watched my comrades communicate their next line of action with locked eyes and a nod.

Stealth is everything. Ms Leti’s second rule which, as you may have guessed, was my second fail. She had just reached for her waistband when it happened—first the buzz, then the ringtone.

Money fall on you … Banana fall on you …

Amaha swore. I cursed, slapping my trouser pocket as if it would stop the sound. It took seconds longer than it would have taken to shut my phone off if my hands had not been shaking. Trembling, I looked ahead; past Amaha’s glare, past Ms Leti’s incomprehension, and straight to what was no longer a dark figure charging towards us. I recognised him immediately. Nnamdi from class … light-skinned, pimple-faced … third row.

Ms Leti ordered me to step back but I couldn’t move, muscles rigid. She pulled out one of her canisters and poured a drop of its content unto her palm. Stretching her palm outward, she blew hard over it and a yellowish wisp of smoke emerged.

‘Are you deaf?’ Ms Leti’s eyes turned a greenish yellow. Amaha acted on my behalf, grabbing my arm and thrusting me backwards. I crashed into the bottom stem of a tree, right next to a mud pile. When I looked up, the smoke had magnified into an illuminated greenish fog obscuring all before us.

Anwuru ife—as Ms Leti had described during training—Reveals the possessed in their true form.

Amaha and Ms Leti stood about three feet away from the fog, combat ready. Amaha brandished his staff like a boulder, ready to strike. From her waistband, Ms Leti pulled a pen-size hollow pipe with a pin-size dart in it and stuck it like a cigarette in her mouth.

Nkwusitu, she’d also described earlier, Incapacitates the possessed.

We waited. Seconds felt like minutes, my breathing loud and heavy. The haze seemed to be dispersing into a faint mist. Until something crashed through. It was not the person I’d recognised earlier, not Nnamdi from third row. It was not a person at all, not with its hollow sockets for eyes and the hyper salivating gape for a mouth. Its pale, chalky white skin appeared almost translucent. The creature landed on all fours, right in-between Amaha and Ms Leti, growling.

I screamed.

Falling back on two feet, it took a swing at Ms Leti, thrusting her into mid-air. She metamorphosed on her descent, landing safely on all fours as a wild cat.

Amaha swung his staff. The creature swerved and the weapon smashed into a tree. The creature’s fist connected with Amaha’s right side, sending him twirling to the ground. Ms Leti, back in human form, blew on her pipe. The dart whistled through the air, narrowly missing its target.

She stepped back, her eyes finding me. ‘Stay down!’ she barked.

Not a chance! I was up and running, as far as my legs could carry me, eyes strained to untangle the darkness. I leaned against a tree a few minutes later, palms on my knees, panting. It was pitch black, the moonlight shaded by the thick foliage overhead. Grass rustled in the near distance. Snakes, I hoped. I pulled out my phone. I was going to call Mama. I was going to tell her that I wanted out of this school, out of this cursed place.

Then I smelled it; acrid, nauseating … familiar. I turned on my phone’s torchlight. The glow fell on stubby ankles. Heart racing, I raised my light slowly—over a red skirt, over a sky blue blouse and onto a dark, pretty face, head full of short curly hair.

‘Ebere?!’ I prayed I was hallucinating.

‘Hi Nedu,’ Ebere’s lips curved into a half smile.

I do not remember much else after that; not when my phone slipped or when my knees buckled. But I do remember the last thought that crossed my mind: Ebere is one of the possessed.

***

One day before resumption of school. My tiny room looked like a wardrobe had exploded in it. I was seated by the window, staring out into nothing in particular; anxious. A crow swooped down and perched on the short brick fence wall that enclosed the front yard of our house. Finally, a worthy distraction. I looked on, reminiscing about those days at the slaughter market when we spent most of our afterschool hours by our mothers’ stalls. I remembered how Atu, Mani and I, with our self-built catapults in hand, would sneak to the back of the market where piles and piles of bones, horns and animal skulls were heaped. The Bone Pyramid, Mani called it. We would watch the vultures glide over discarded carcasses, oblivious to the fact that they too had become prey. I remembered the snap of our rubber straps and the swoosh of the stone missiles. I remembered the terrific thud, how we all gathered around the fallen in sheer delight.

‘Nedu, you hit again!’ Atu never failed to cheer. Smug, I’d raise my catapult, eager to put the twitching bird out of its misery.

‘Nedu!’ Mama’s voice brought me back to the present. She wore a loose wrapper across her chest and a frown on her face. ‘Don’t you want to start school tomorrow?’

Not if I could help it. Lagos, Enugu, Owerri—those had been my choice locations for Senior Secondary. But when Sacred Heart College called—out of the blue—offering a scholarship, my parents made them my only choice. Before then, I’d hardly heard of the school. The much I knew was that it was situated in my maternal village of Aguba.

Also, I’d always considered myself an average student by every measure, B-Plus at best. So initially, I was sceptical about the authenticity of the offer. Not until I was singled out during registration and led into the Registrar’s office, by-passing the long queue at the bursar’s. Within minutes, I was fully registered—with an ID card and pink slips to show.

In less than a week, I sat for my first lesson in a packed classroom—with its pane-less windows and dilapidated benches, its graffitied walls and gritty concrete floors. My classroom was on the ground floor of a three-storey rectilinear block, lined with long balconies on each floor and dingy stairwells with perforated walls. Students trooped in, trailed by whiffs of cheap perfumes and scented talc, of new leather and starched shirts. Most were indigenes of Aguba and the rest from not far off. I looked up to the whitewashed ceiling, contemplating what I believed would be the most uneventful three years of my existence.

My friend Jerry was on top of his desk, next to mine, bobbing his head to the loud music that spilled out through his chunky headsets. We were dormitory mates and had bonded over our love of crass Nigerian music, in addition to being in the same class.

‘Guy, Davido’s new song is ba-ad!’ Jerry pulled off his headphones and placed it over my head. Davido’s voice and Afrobeats filled my ear:

Money fall on you … Banana fall on you …

I was sold. In seconds, the Bluetooth of our phones synched and I was changing my ringtone.

An order from behind made Jerry jump off the desk.

‘No phones in the classroom!’ The shrill voice did not seem to be that of the heavy-set man now standing before us with a hard jaw and a receding hairline. The right leg of his loose, brown trousers was tied to a knot at the knee; the rubber stub of his intricately carved walking stick recompensing in step with his one foot.

Mr Kosisochukwu Okpara—History, the new teacher scribbled on the black board. ‘You’ll soon join your mates in calling me KO.’

‘Knock Out!’—came a murmur from behind. A few giggles erupted. Bubble gum popped. Mr Okpara narrowed his eyes but said nothing. A few tardy students trooped in. That was the first time I smelled it. Body odour, I’d presumed. But then body odour would not have made my eyes sting or my fists clench.

I leaned over towards Jerry. ‘What’s that smell?’

‘What smell?’ Jerry looked confused at first, then grew concerned when he noticed my eyes tearing up. I looked around the classroom, trying to determine the source of the smell. No one stood out. It had definitely come in with the last set of entrants. I looked to the front of the class and caught Mr Okpara’s darting eyes—his grimace reflecting mine. Our eyes met and our shared discomfort was communicated almost instantly.

‘Master Agunta!’ Mr Okpara eyes were still fixed on me.

‘It’s Okwuosa, Sir. Chinedu Okwuosa.’ I rose to my feet, rubbing my eyes with my palms.

‘Do you know my office?’

‘No, Sir.’ My muscles ached and pumped at the same time. The stale bread and weak beverage I’d had at the refectory for breakfast threatened to resurface. It was a weird combination of aggression and agitation.

‘Do you know the Library store?’

‘Yes, Sir.’ I lied, eager to sit back down.

‘Good. Meet me there after lunch,’ Mr Okpara said. ‘Now, leave my class!’

‘What?!’ Jerry’s outburst was proof that I’d heard right. That and the murmurs that ensued from the rest of the class.

‘Now!’ Mr Okpara’s eyes turned fierce.

Wedging my belongings against my chest, I ran out of the classroom. The scorching sun was as welcoming as the hot air it harboured. I could breathe again. My body calmed, my stomach relaxed. I looked at my watch. Ten past nine. Lunch was at two. I thought about waiting for the next class but my stomach churned at the thought of going back into whatever that smell was. I was forced to mark my first day of school by breaking the rules and skipping all the day’s lessons. Betting on the odds that no one would notice my absence, I snuck back to the dormitory and laid low until two in the afternoon.

***

Lunch at the refectory offered watery egusi soup and rock-hard garri. An array of long wooden tables sandwiched by equally long benches quickly filled up with a swarm of hungry students. I sat next to Jerry. He was busy rubbing copious amounts of Vaseline over the exposed parts of his body, so much so that I feared he might slide off the bench.

In all this heat? I wondered.

‘Can I have some Vaseline?’ A velvety voice from behind us. I looked up to see a pretty, dark girl with a sheepish smile, carrying her food tray with both hands. I remembered her from class. Jerry gave her his small tub and soon he and I were adjusting to make room for her on our bench. She introduced herself as Ebere and I was immediately conscious that her knee and mine were touching. She asked if I was still meeting Mr Okpara after lunch. I was surprised she remembered. I admitted lying about knowing where his office was.

‘It’s the red metal door at the back of the library,’ Ebere said. ‘You can’t miss it.’

I nodded, then leaned close. ‘Did the class smell weird to you?’

Jerry rolled his eyes. ‘Guy, you’ve come again with this your smell.’

Ebere also seemed clueless about the smell. So we talked about Davido and more Nigerian music, the places we’d been, and some of the interesting characters in our new class. In less than an hour, lunch time was over and we all trooped out of the refectory. Most of the students headed back to their dormitories. I found my way to the library.

Ebere was right. The metal door was easy to spot. It was slightly ajar and led into a hallway with three doors. The first two, on the left side, were restrooms. The last door, on the right, was at the end of the hallway that linked back to the main library building. It was a large wooden door with no handle. I ran my fingers across the intricate carvings on its surface; they looked like ancient African hunters brandishing bows and arrows, guns and spears. The top casing of the door held a paper note with the inscription: OUT OF BOUNDS. Wrong door, I presumed, and had turned to leave when I heard the door creak. I turned back to a slightly open door.

‘Hello?’ I peeped through the opening before abandoning all common sense and stepping in. The room was a store indeed. Stacks of damaged shelves, broken desks and stacks of chairs, all enveloped in a surfeit of dust and cobwebs. A library junkyard. The door glided shut behind me, as unaided and as quietly as it had opened.

‘Hello?!’ I called out.

My ears picked on distant voices coming from farther into the store. I trod quietly along a narrow clearance that cut through the middle of the junk pile. The narrow path curved as the heap stretched, its contents diversifying from broken furniture to discarded electrical appliances. At the end of the pile stood several large, high bookshelves with their backs to me. The voices had become more audible, coming from the other side of the shelves. I recognised one of the voices, hushed but distinct.

‘Mr Okpara, It’s me, Chinedu Okwuosa.’

The voices went quiet. A chair moved and the sound of a wooden cane tapped on the terrazzo floor.

‘Master Agunta?’ Mr Okpara emerged, seeming surprised to see me. He motioned me to the other side where a long wooden table sat, as rustic and exquisite as the door; with similar carvings on its legs and sides. Seated around the table were an old man Mr Okpara introduced as Oguejiofor; a petite lady, Ms Leti, with her hair drawn into short loose locks; and a tall lanky lad, Amaha, who was busy sharpening one end of a short stick with a pen knife. He wore the same dormitory uniform as me—blue shirt and maroon trousers. Mr Okpara went on to introduce me as Master Agunta.

‘Okwuosa, Sir,’

Mr Okpara smiled. ‘I’m more interested in your other name.’

‘My other name is Chinedu, Sir.’

Mr Okpara shook his head. ‘Isn’t your mother nee Agu? It used to be Agunta till it was shortened. Your great-grandfather was one of Aguba’s greatest hunters, Dinta as we call him.’

Mr Okpara pointed at the seat next to Oguejiofor, who squinted with his one good eye at me. His left eye was all white like a boiled egg and never blinked. He was clearly the oldest in the room, his thinning white hair compensated for by a thick white beard.

‘He looks nothing like Agunta!’ Oguejiofor said with a hint of disappointment, his mouth smothered with whitish splinters from his chewing stick. Ever so slight was the hint of dried urine sifting through his loose, grey overalls. I looked to Mr Okpara, my eyes begging for some explanation.

What was going on? Was I in some kind of trouble? What was all this talk about my mother’s family and hunters?

Mr Okpara took to the seat at the head of the table, cleared his throat and began a history lesson. ‘Before colonisation, the Aguba were a typical Igbo community, specifically known for hunting. Our Chiefs were among the few that proudly wore leopard skins on their backs and drank palm wine from elephant tusks. And like every Igbo community, we had our unique traditions and customs.’

‘Ome n’ala.’ Ms Leti sighed, wistful.

Mr Okpara continued, ‘Amongst these customs were atrocities we committed against our fellow humans. You’ve heard of the evil forest before, haven’t you?’

I frowned, not sure how to respond. As far as I was concerned, ‘evil forests’ were synonymous with Nollywood movies and ancient fables. Mr Okpara didn’t wait for an answer.

‘We banished evil doers to the evil forest. But these also included outcasts and some innocent women presumed to be witches … even mothers of twins.’ His mood turned pensive. ‘You can’t blame our forefathers. It was the level of their consciousness at the time. Even the Scottish, back in the day, used to …’

Oguejiofor grunted, tapping on his watch-less wrist. Mr Okpara smiled awkwardly. ‘Let’s fast forward to when colonisation came and condemned all inhumane practices. Churches and schools replaced shrines and evil forests …’

Mr Okpara got up from his seat and walked over to a shelf that held a fair number of thick, hardcover books. He pulled out one of the larger tomes and dropped it in the middle of the table. Dust soared. Ms Leti and I sneezed. Oguejiofor exhaled hard, rubbing his nose vigorously. Mr Okpara flipped through the pages in chunks until he got to where he wanted. He pointed to a faint stringy line map with labels that appeared handwritten.

‘This is the old map of Aguba dating back to the 19th century. There’s the Eke Market, it’s still in its same location; there’s the old Chief’s palace, now the residence of the Ezennaya family. There’s the village shrine where Oguejiofor’s forefathers thrived.’

Oguejiofor grunted again.

Mr Okpara traced his finger down to an encircled space at the south end of the map. ‘That’s the infamous evil forest, reclaimed by the British and used as the site of Aguba’s biggest college.’

I looked up at Mr Okpara. ‘Isn’t our school the biggest in Aguba?’

He nodded. ‘And in most of Anambra North. In 1946, just months after Sacred Heart College was commissioned, three students went missing, and two returned home completely different persons. By 1950, the number was in the dozens. The school board turned a blind eye. Until Elder Oguejiofor, a powerful native doctor whose Christian convert granddaughter was one of the missing, resolved to get to the root of the matter. He did. Turns out that the souls of the banished had become restless spirits trapped within the dreaded confines of the evil forest. Building the school on the forest grounds presented an opportunity for evil spirits amongst the dead to live again—by possession.’

He paused to let it all sink in. To my surprise, his stories didn’t scare me, and even more so as I somewhat believed every word he said. I asked what happened to the bodies when they were possessed.

‘There is a gestation period of thirteen days during which the bodies are gradually overtaken by these spirits. On the thirteenth day, the host bodies become theirs completely. When Elder Oguejiofor made the community aware of his findings, the converted Christian majority shunned him, regarding him as ‘fetish’.

The History teacher flipped through a few more pages. Ms Leti sneezed. I sneezed. Amaha rubbed his eyes. Mr Okpara stopped on a new page showing drawings similar to the carvings on the entrance door—a group of sparsely clothed hunters, each with a distinct hunting tool.

‘Your great-grandfather Agunta, an unwavering traditionalist.’ Mr Okpara pointed to a hunter that carried a crooked bow.’He believed Oguejiofor’s story and immediately called on a few trusted huntsmen. They entered into a covenant to rid Aguba of these evil spirits.’ Mr Okpara paused to look at my face, then continued.’ My forefather and Amaha’s were part of that expedition to hunt down the possessed. If caught in less than thirteen days since possession, the bodies are tranquilised and the native doctor can cast the spirit permanently into the land of the dead.’

I looked around the table and back to Mr Okpara, quite certain I’d figured out why was summoned. ‘Sir, do you need me to help write a book about my great-grandfather?’

Amaha, who’d been quiet the whole time—knifing away on the now very pointed tip—burst into mirthless laughter. Ms Leti slapped his arm.

Mr Okpara became pensive. ‘We need you to fill your forefather’s shoes. We need you to help us hunt the possessed.’

I trembled. ‘The possession has started again?’

‘My dear, it never stopped,’ Ms Leti’s said.

I looked around the table, terrified.

‘So, he’s a descendant of Oguejiofor?’ I pointed at the old man.

Mr Okpara nodded. ‘He makes charms and casts out spirits.’

‘And they are both hunters?’ I gestured towards Ms Leti and Amaha.

‘Ms Leti is part of the combat team, but she’s not a native of Aguba. She’s a shifter, from the neighbouring village of Arodi.’

‘A Shifter?’ I turned to Ms Leti.

‘That’s a story for another day.’ She smiled, her hazel eyes gleaming.

Mr Okpara explained that they were all members of Sacred Heart College. Oguejiofor taught Agriculture, Ms Leti—Social Studies, and Amaha was in SS2.

‘No, No, No!’ I was up, making my way across the table. Things had taken a turn from intriguing to downright scary. I was a Christian and this sounded like a secret cult.

Mr Okpara banged the book shut. ‘Master Agunta, why do you think you were awarded a scholarship by Sacred Heart?’

It was obvious now. But I didn’t care. I was more than happy to have it revoked. Mr Okpara raised his cane and blocked my path as I made to march past the shelves.

‘Master Agunta, we went to great lengths to get you into this school. We put our identities at risk when we involved the VP Admin to grant that scholarship. With the decline of traditional religion, the sacred walls of the forest are wearing thin. In less than a year, these spirits will no longer be contained within the walls of the college. Then there’ll be nowhere to hide in Anambra. We need you as much as you need us. As a hunter, you will be alerted by smell whenever you encounter the possessed. Remember class this morning,’

I froze. ‘There’s one in our class?!’

Mr Okpara nodded, ‘If I had not sent you out, you would have become hysterical. You are born to hunt.’

I tried telling Mr Okpara that I couldn’t hunt, which was not entirely true. Much of my childhood was spent hunting—from birds to small prey like lizards and rats—fast creatures that offered a challenge. I was one of those weird kids with such morbid thrills.

‘Amaha and Ms Leti will coach you. Master Agunta, I know this may sound scary but if you could sit back down, I promise to demystify things further.’

With forced restraint, I complied. Mr Okpara, however, failed on his promise. The stories only became more mysterious, the danger more real and every ounce of my body pleaded for escape. Before I left, Mr Okpara handed over a small cylindrical cup filled with a brownish powdery substance.

‘Utaba. Helps with the smell. Dab just a pinch at the tip of your nostrils. Use only when a possessed is near and you have identified who they are. Be careful, a little extra could make you hallucinate.’

The dinner bell sounded just as I walked out of the Library. I found Jerry and Ebere seated at the back end of the refectory.

Jerry slapped me on the back. ‘Guy, what did KO want?’

‘Nothing much. Just a long lost relative on my mother’s side.’

Jerry immediately lost interest, putting his headphones back on.

‘That’s nice,’ Ebere said, offering a smug smile.

***

It was that very same smile that Ebere had, days later, when my phone’s torchlight fell on her face, right before everything went blank. Next thing, I was gazing at a discoloured white ceiling with a noisy fan swirling in the middle. The air was saturated with the distinct smells of Izal and bleach. I turned to see Mr Okpara sitting at the edge of my bed.

‘What happened?’ I struggled to find my voice.

‘You passed out.’

I asked about Ms Leti and Amaha.

‘They are back. Mission was aborted’

I apologised for ruining the mission; for my phone ringing. If Mr Okpara was disappointed or upset, it didn’t show.

‘We’ll catch him next time,’ was all he said.

I jerked up immediately, remembering Ebere. ‘And her! The girl in my class. I saw her in the forest. She had the smell.’

‘Ebere.’ Mr Okpara placed a hand on my shoulder and pressed me back down to the bed. ‘She’s the one that alerted us to where you fainted. She used to be one of us.’

‘She’s a hunter?’ I immediately felt relief.

Mr Okpara cleared his throat ‘On the contrary. She’s one of the possessed, but harmless. She’s been in this school since JS1. When we found her, she had already fully displaced her host’s spirit. She begged to join our fight against her kind and she proved to be quite resourceful until we realised that she had ulterior motives.’

‘Ulterior motives?’

‘Revenge. Against the spirit of the evil man who framed her. So we banned her from the group.’

I wanted Mr Okpara to explain further but he said it was a long story for another day. My head started to hurt, probably from all the confusion.

‘How come I didn’t smell her before?’ I asked ‘We were together in class and ref for days.’

Mr Okpara shrugged. ‘That, I don’t know. You should’ve perceived it in an instant.’ From his side, he pulled out a small dagger encased in a leather pouch. ‘Keep this, just in case.’

‘Thank you, Sir.’

‘You’re welcome, Master Agunta.’

‘Sir, will you ever call me by my real name?’

He mused. ‘I could, if you learn to call me KO.’

KO stayed with me a little longer before leaving. I spent the night at the sickbay but was back at my hostel early the following morning, still feeling a bit sore. It was a Saturday, so lethargy prevailed throughout the entire hostel, as did the smell of laundry detergents. I met Jerry seated at the bottom of his bunk bed, with only a towel to his waist. As usual, he was applying alarming amounts of Vaseline to his entire, moist body. I immediately blurted out my rehearsed lie of spending the night in the sick bay after developing malaria symptoms.

‘Oh.’ Jerry glanced towards my unmade bed.

I realised he hadn’t noticed I had been gone all night.

Jerry rubbed his head. ‘I dozed off very early, kept having crazy dreams about forests.’

My pocket buzzed and Davido’s music filled the air. I made a mental note to change my ringtone. It was KO calling and immediately muted it. I’d had enough of the supernatural for one week. A text came in less than a minute later;

Okwuosa,

Oguejiofor has figured out why you couldn’t smell Ebere. It’s Petroleum Jelly. Seems like a few have discovered that it masks their smell from hunters. Be careful. KO

I looked up at Jerry.

‘What?’ Jerry frowned ‘You look like you’ve seen a ghost?’

‘Nothing.’ I tried to remain calm, quickly replying KO with our agreed SOS text.

‘So, Jerry.’ I forced a smile, my hand resting on the hidden dagger tucked at my left side. ‘Tell me more about these forest dreams you’ve been having.’

~~~

- CJ Enemuo is a lecturer in urban and regional planning, an urban design architect, arts curator and creative storyteller and the founder of Nelen Studios.