The JRB presents an excerpt from Civilising Grass: The Art of the Lawn on the South African Highveld by Jonathan Cane.

Civilising Grass: The Art of the Lawn on the South African Highveld

Jonathan Cane

Wits University Press, 2019

Read the excerpt:

~~~

No gays, no blacks, no dogs

I now turn my attention to Joubert Park in the densely populated centre of Johannesburg. Attached to the distinguished Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), it was once the premier promenading ground of the Edwardians, and later a thriving core of bohemian, semi-multiracial, high-density urbanism. It has, since the so-called white flight into the suburbs during the nineteen-nineties, become a complex neighbourhood of migrants and foreigners making new uses and making do. It is singular in its ability to evoke a peculiar form of urban nostalgia and the associated melancholy of failed urbanity. As Aubrey Tearle, the grumpy narrator of Ivan Vladislavić’s novel The Restless Supermarket, says about Hillbrow’s decline: ‘Where once there had been benches for whites only, now there were no benches at all to discourage loitering. The loiterers were happy to lie on the grass, but, needless to say, I was not’ (Vladislavić 2001: 15). The idea of reuse, of getting by with remnants, is at odds with the established concept of the lawn, which does not suggest a proliferation of alternatives and multiple uses. There is a singularity about the lawn’s intention. Inherent and often explicit in the lawn trope are a number of exclusions, prohibitions, injunctions and exhortations. The commandments of the public lawn are directed towards the formation of well-behaved and respectable subjects. By examining some of the least respectable practices and those subjects who have used and been forbidden to use the park historically, it is possible to offer a queer analysis of this landscape’s dark side.

Joubert Park was established in 1887 at the request of the Diggers’ Committee, Johannesburg’s earliest local government, as a ‘public park or garden to be planted with trees’ (Bruwer 2006: 107). Marked Joubert’s Plein on an 1889 stand map, the park was named after General Piet J Joubert, commander-in-chief of the Transvaal military forces (105). The land was ploughed in 1891 and planted with seeds and seedlings, some of which were donated by Kew Royal Botanic Gardens (Van Rensburg et al. 1986: 177), and by April 1892 The Standard and Diggers’ News reported that the park ‘speaks volumes for the richness of Rand soil. Already the grounds are perfectly lovely with shrubs and flowers’ and the benches ‘are always occupied by engrossed couples’ (quoted in Bruwer 2006: 105).

In 1895 some indigenous trees were added to the botanical transplants, followed by a central ornamental fountain with a rockery and water flowers (Bruwer 2006: 105), and in 1898 a conservatory, bought from the Wanderers Club, was added. In 1906, Joubert Park was donated by the government to the Johannesburg Municipality ‘for the purposes of or incidental to the recreation and amusement of the inhabitants’ (Crown Grant No. 268/1906, 22 May 1906, Rand Townships Registrar, Johannesburg).

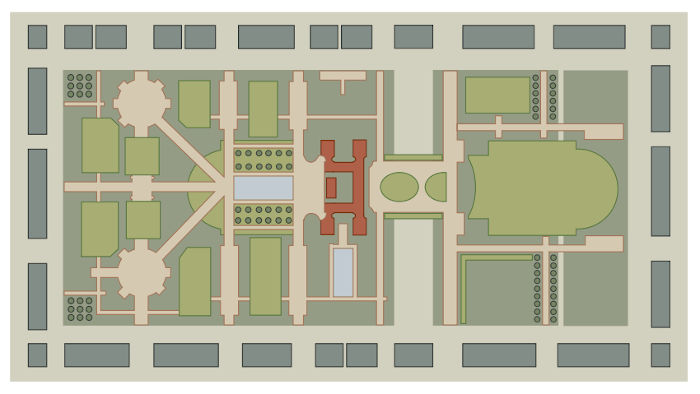

JAG was conceptualised by Florence Phillips and Hugh Lane, and opened in November 1910 in temporary premises before moving to its final home in 1915. As part of Edwin Lutyens’s design, he proposed doubling the size of Joubert Park by constructing a wide causeway to span the railway tracks and include Union Ground (later known as Jack Mincer Park and now the location of Park Central Taxi Rank). The changes would have placed JAG in the centre of a generous twenty-acre park. As can be seen in Plate 18, Lutyens’s plans envisaged Joubert Park as the rear garden, with the front park being treated as a cour d’honneur (three-sided courtyard) with formal lawns. The proposed park drew on a ‘mixture of grand scale and intimate elements, related to major, minor and converging axes’ (Bruwer 2006: 108).

Joubert Park had neither a singular designer nor a singular design, but the cumulative intentions—sometimes ad hoc, sometimes formalised, as was the case with Lutyens’s plans—were in accord that the park should be a place for the conspicuous display of wholesome leisure. The goal was ‘to design a park which required becoming behaviour; behaviour which would fit the visitor not just for an afternoon’s polite stroll, but also encourage him to fulfil a role deemed appropriate and useful within the community’ (Taylor 1995: 214). The formal architecture of the eventual park design, set on an axis with a symmetrical arrangement, created not only a sense of order and clarity in the dusty mining town but also spaces for public sitting and promenading. The Victorian idea of conspicuous performance is evident in a number of turn-of-the-century postcards (Norwich 1986: 76), which show scenes of white women in ‘pouter pigeon’ blouses and trumpet skirts with oversized hats strolling with men in three-piece suits and smart hats. In these postcards, the lawns have been tinted in an optimistic green and the bedding schemes painted with sharp and bold colours.

In ‘The Virtuous and the Verminous: Turn-of-the-Century Moral Panics in London’s Public Parks’, Nan Dreher (1997: 252) argues that the discourses of ‘rational recreation’ and ‘social purity’ were the two most important concepts at work in late nineteenth-century metropolitan crises over public indecency. On the one hand, proponents of so-called rational recreation (sports, family picnics and the enjoyment of nature) pictured idealised middle-class citizens as models of sober, abstemious public comportment; the performance of respectability was hoped to have what was then called a ‘healthful influence’ (253). On the other hand, social purity advocates mapped fears about hygiene and health onto public sexual activities (courtship and prostitution) and the public visibility of homeless or ‘verminous’ persons (258). That these concerns could be located on the lawn is clear from the archival material Dreher collected. For instance, in 1918 the London Council for the Promotion of Public Morality complained: ‘Twenty or thirty years ago the limit of alfresco courtship recognised by ordinary folks extended as far as placing an arm round a lady’s waist, whilst sitting on a seat. Now the seats … are discarded in favour of lying full length upon the grass’ (quoted in Dreher 1997: 257).

No sex

In Queer Ecologies (2010) Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson point out that the emergence of European public parks in the mid-to-late nineteenth century coincided with a growing social panic about the proliferation of non-normative sexual types and expressions. They argue that the ‘naturalisation of (apparently fragile) heterosexuality’ found expression in the conspicuous display of middle-class respectability and the promotion of the park as site of moral upliftment, especially of the working-class (2010: 13). Conversely, Mortimer-Sandilands and Erickson suggest that in this context what is significant about sex in parks is that it is public,

meaning that it overtly challenges heteronormative understandings of what is appropriate behavior for public, natural spaces. Here, we must remember that public parks are disciplinary spaces, in which a very narrow band of activities is sanctioned, practiced, and experienced; only certain kinds of nature experience are officially allowed. In this context, one can consider public gay sex as a sort of democratization of natural space, in which different communities can experience the park in their own ways, and in which a wider range of natural experiences thus comes to be possible. (2010: 26)

Matthew Gandy offers the notion of ‘unruly space’ for describing arenas that ‘do not play a clearly defined role, or which are characterized by ill-defined use or ownership, or that have been appropriated for uses other than those for which they were originally intended’ (2012: 734). He argues that activities like public sex and cruising are ‘forms of site-specific spatial insurgency’.

Mark Gevisser’s research provides a singular resource for the exploration of Joubert Park’s public sexual exuberance. As co-editor, with Edwin Cameron, of the groundbreaking queer volume Defiant Desire (published in 1995), in his role in co-curating the exhibition Joburg Tracks in 2010, his involvement in the documentary film The Man Who Drove with Mandela (Schiller 1999) and in his book Lost and Found in Johannesburg (2014), Gevisser has gathered together one of the very few collections of fragments about this central space. Two recurrent characters—Phil and Edgar—provide the narratives for much of Gevisser’s memory making. Both men were ‘after nines’; that is to say, black gay men who lived ostensibly heterosexual lives before nine o’clock at night, when, with their family asleep in the township, they would pursue queer encounters, often in the ‘white’ city. Gevisser writes about Phil and Edgar’s youth, around the time of the Second World War, when Joubert Park began to take on an important role for male gay life:

Having delivered the goods for his mother, Edgar told me, he would go ‘fishing’—as he liked to put it—in Joubert Park or at Park Station on his way back to [Pimville]: ‘I was sixteen, a Zulu boy. Hefty! Plumpy! I wore shorts, very tight shorts! I was a fit young boy; men of all races would be attracted to me.’

Delivering washing for his mother provided Phil, too, with access to the city: he was seduced by one of her clients, and realised the possibilities of the world beyond Soweto. He dropped out of school, much to the fury of his parents. ‘I was too streetwise,’ Phil explained to me. ‘I liked the money. It was my chance of meeting men.’ One of Phil’s favourite haunts was Union Grounds, in Joubert Park, where white soldiers were barracked after the war. ‘He is on one side of the fence and you are on the other, he pulls down his pants, and puts his whatsisname through the fence, and you put your hands through the fence to get hold of him, and you do your thing. There and then. And he gives you two and sixpence.’

When I asked if he was worried about being seen, he deadpanned back: ‘The lights in those days were not as bright as the lights today.’ (Gevisser 2014: 194)

The tightly circumscribed domestic arrangements of family life, embodied and structured by the tiny black family homes of the townships where Phil and Edgar lived, influenced the spatial order of their sex lives. In the patriarchal order, under the apartheid vision of black family life and gender roles, places like Hillbrow and Joubert Park potentially provided blurred spaces for the articulation of difference and subversive connections. On a practical level, Joubert Park was one of the very few places where black and white men could encounter each other. Phil and Edgar describe the ‘possibilities of the world beyond Soweto’ as a certain kind of worldliness, a world of interracial relationships (characterised, of course, by profound asymmetry), money, sexual liberation and physical freedom to wander. The following is from the film The Man Who Drove with Mandela:

Gay life in Johannesburg was very tough. To be gay back then as a black man, one had to be rich, because, point number one: you had to have your own privacy. Blacks by then, if you are not married, you were not allowed to have a house. Number two: you wouldn’t come into town to enjoy your gay life, to stay in a hotel. There were no hotels for blacks. We had to stand outside the gates of Joubert Park or go to the Union Grounds’ soldier barracks; there were a lot of soldiers there. They were white. Nobody who was not gay would come near the fence. (Schiller 1999)

The film also includes the following monologue attributed to Cecil Williams, reminiscing about early life in Johannesburg:

On my way from the university I used to linger in Joubert Park. I was quite taken aback when an older man struck up a conversation with me and invited me to his flat. Really, I’m amused when I think about it now. The mere mention of the word flat—a flat, oh. The connotations were fabulous. One knew that all sorts of abominable things went on there. My seducer offered me a drink: a gin and lime. For years after just the smell of gin and lime signalled a sexual experience. (Schiller 1999)

By the time the soldiers eventually left, a gay subculture had stubbornly planted itself in Joubert Park and in Hillbrow more generally. Park Station, adjacent to Joubert Park, became a famous site for cruising (Gevisser 1995: 18–19) and picking up rent boys (Galli & Rafael 1995: 136). There were also bars, clubs, bathhouses and gay-friendly bookstores. Through the nineteen-fifties and nineteen-sixties, there were periodic crackdowns on homosexual activity, particularly at those edges of the park where black men and white men met, such as the post office steps on Wolmarans Street (Gevisser 2014: 197–198), leading to numerous embarrassing arrests. After the decriminalisation of homosexuality, Hillbrow accommodated some racial mixing in gay bars and the pride march in 1990 (172).

No rest

In London at the end of the nineteenth century, members of the public expressed outrage about the ‘thousands of verminous and infected people lying on the grass’ in public parks (quoted in Dreher 1997: 265). Their anxiety about indolent men, and especially the potential of their spreading communicable diseases, caused the London Office of Works, in 1913, to consider the issue of disinfecting lawns: ‘The question of disinfecting the grass has been considered but the use of a solution of paraffin or similar liquid would be very objectionable and disinfectants would tend to destroy the grass’ (quoted in Dreher 1997: 264). Dreher presents a 1902 photograph of St James’s Park depicting sleeping men ‘strewn thickly over the grass’ (262).

Contemporary South African writers and artists have not missed the opportunity to observe (black) men sleeping inappropriately on the lawn. For instance, in Johannesburg Circa Now (2005) Melinda Silverman and Msizi Myeza compare a vintage postcard showing promenading white Edwardians in Joubert Park circa 1904 with the parallel image of black men sleeping on the park’s lawns ‘circa now’. On the one hand, the observation is surely true enough: as they point out, a century later there are fewer white people, more black people, fewer women and more people sleeping. It is the same observation one could make of Welkom Central Park comparing 1955 and 2005. On the other hand, one has to ask: what is at stake in pointing out this particular use as opposed to, for instance, excavating the unsavoury sexual patterns of the park?

In his blog The Death of Johannesburg the ‘Real Realist’ explains that Joubert Park ‘used to be a place where the city council put up Christmas lights, where choirs would sing Christmas carols … nowadays it’s just a slum with squatters living there’. The blog features a few grainy shots of the park from a car window, which the author—and the many readers who have commented in the threads attached to his blog—seem to believe makes a compelling case for an apparent racial cause for current failures. There is, as elsewhere in the discourse around Hillbrow, a vivid nostalgia for ‘the good old days’, emblematic of a broader concern with the city in decay and the loss of a way of life. In a similar fashion, Vladislavić’s Aubrey Tearle catalogues the ‘decline’ of Hillbrow, describing, in explicitly hygienic terms, the ‘new varieties of dirt on the pavements’:

Sticky black scabs on the cement flags, blotches, bumps, nodules that cleaved to the soles of my brogues. More of them all the time, like some skin disease. What is this stuff? Where on earth is it coming from? You never saw it falling from the sky or spilt by a human hand. It seemed to be striking through from beneath, like some subcutaneous festering. A less fastidious man than myself, a man more accustomed to taking specimens, an indigent geologist, say, a botanist, a pathologist, might have made a study of it to determine its origins. Animal or vegetable? (Vladislavić 2001: 51–52)

Tearle’s affective inventory of decline is written as a diagnosis, observed with the eye of a pathologist.

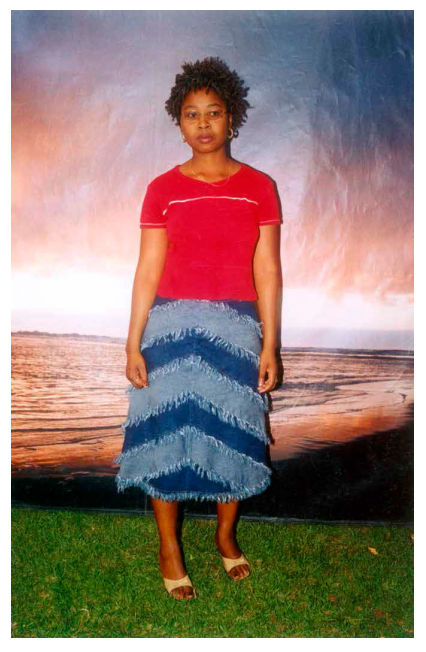

Terry Kurgan, as part of her Park Pictures project, mapped onto a large aerial photograph the location of the forty portrait photographers who worked in Joubert Park at the time (see Plate 19).

of forty photographers working out of Joubert Park in 2004. As part of her Park Pictures project (2005), Kurgan documented the professional photographers who made a living taking portraits in the park outside the Johannesburg Art Gallery. Image courtesy of Terry Kurgan.)

This cartographic work indicates the concentration of photographers on the east–west axis, the major vector of movement through the park. The photographers and many of their clients have roots elsewhere: ‘They have migrated to Johannesburg from other parts of the country and the continent to find work and better lives. The position each photographer occupies is sacred, and the right to occupy a particular wrought iron bench, a large rock on the grass or a low wall perch along a cobbled pathway, is often purchased or negotiated as far away from the inner city of Johannesburg as a rural village in Mozambique or Zimbabwe’ (Kurgan 2003: 468–469).

Tamar Garb points out in Figures and Fictions that the park’s lawns, fountains and gallery produce ‘ready-made picturesque settings’ (2011: 68). Through the clients’ photographic interactions, the park becomes a situation, one in which the scenic potential of colonial/modern aesthetics becomes the set for staging a claim on a kind of urbanity and black modernity, a form of ‘cityness’. David Bunn argues that the park is ‘part of the mise en scène of a larger plot involving Johannesburg and the continental imaginary: desire of migrants and work seekers, from Kinshasa to Beira, to find jobs and enrichment in Johannesburg, and to move through the city fluently, like a native. For African working-class subjects, this drift into the city has always, since the origins of migrant modernism, been anchored with representational acts’ (2008: 157).

The lawn appears in a great number of the images Kurgan collected from the park photographers. By buying up numerous uncollected images—those prints the photographers had kept for clients who did not return—Kurgan built up a fascinating archive (see, for example, Plates 20 and 21).

These images were curated inside JAG, spliced with portraits from the gallery’s permanent collection and with formal portraits of the park photographers taken by Kurgan. In addition to the curatorial component of her project, Kurgan collaborated with the photographers to fund and construct a mini studio, which featured printed backdrops. The choices made by both photographers and clients regarding the backdrop imagery and their poses and gestures highlight modes of meaning making and self-articulation. The two-dimensional backdrops partly screen off the ‘real’ life of the park while the lawn persists as a remainder and reminder of the park.

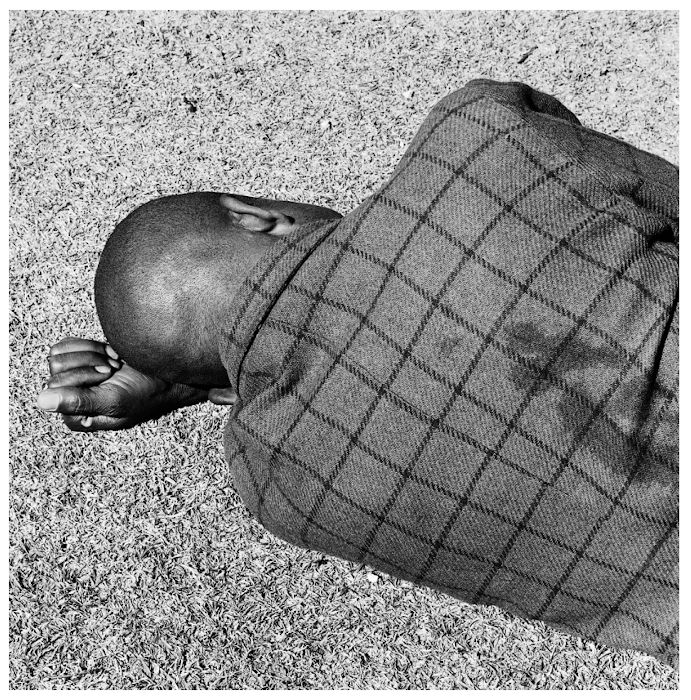

South African photographers David Goldblatt and Pieter Hugo have both trained their lenses on black men sleeping on the lawn. Hugo’s Green Point Common, Cape Town, 2013 is shot on the contested Cape Town promenade late after apartheid. In this colour photograph, the grass is dense, spongy and comfortable. The man lies flat on his stomach, fast asleep. Goldblatt’s black-and-white photographs were made much earlier, during a brief liberal phase after 1974, when the Johannesburg City Council relaxed the application of the 1953 Reservation of Separate Amenities Act and allowed black people to access Joubert Park and JAG (Silverman & Myeza 2005: 44). ‘Man sleeping, Joubert Park, Johannesburg. 1975’ and ‘Sleeping man, Joubert Park, Johannesburg. 1975’ (see Plate 22) were part of a series called ‘Particulars’, which is an unusual collection for the close attention it pays to small gestures and close-ups of body parts, and because of its strange sensuality. Men and women—sleeping, waiting, sprawled, at play, smoking, dressed for an occasion—are observed with unnerving clarity.

Goldblatt appears to have shot the sleeping men at midday: the grass is overexposed and rough-looking and does not suggest a comfortable resting place. Sean O’Toole writes that ‘clasping his hands over his head … rest is something to be defended as much as stolen’ for Goldblatt’s sleepers (2014: 8). Rest assumes a comfortable resting place and can be construed in a binary opposition with gainful employment. These photographs depict neither rest nor leisure, but rather exhaustion. The photographs only become readable against the background of the history and ideology associated with the lawn. From that perspective, sleeping on the lawn in the way the two black men do is undoubtedly a desecration: an appropriation of the lawn for purposes that are foreign to its intent. Hannah le Roux has suggested two alternative ways of conceptualising modernity after the end of colonialism, apartheid, modernity itself, the belief in modernity’s promises:

Vision 1: The project of modern architecture is a failure in Africa. The buildings are shells, void of any aesthetic qualities that are respected by their tenants, and impossible to maintain. Vision 2: The buildings are, on the other hand, highly lively and animated settings, replete with sounds, social relations and multiple functions. In this vision they are preferable to the sterile modernisms of Western institutions that are the backdrop to everyday lives characterised by monotony, order and cleanliness. (2005: 52)

The first mode is exemplified by the ‘Real Realist’ and his neurotic photographs of the outside of the park, shot from a moving car. The second is less common. Take, for instance, a little-known landscape photograph, A space of waiting (2012) by Sabelo Mlangeni (see Plate 23).

In a strangely compelling, romantic treatment, the image is shot from a shady location facing south from the north side of Joubert Park. A dark coulisse on the left side frames the scene according to a Claudian scheme. The trees, captured with a painterly quality suggesting swirling clouds, cast shadows in the foreground. The neo-classical treatment makes it easy to imagine a leisurely picnic happening under the shade. One has the distinct impression that Mlangeni was sitting (lounging?) when he took the photograph. While the ‘Real Realist’ shoots from his car at speed and Goldblatt is the flâneur, Mlangeni waits. In Apartheid & After O’Toole suggests that Mlangeni’s power is as ‘an observer of people. His own presence goes unnoticed … His playful observations are nevertheless rendered with great eloquence and precision’ (2014: 10). The photograph captures a profoundly un-anxious, gentle and even pretty aspect of the park. How, we might ask, can the pictorial language of the picturesque be seen as appropriate for representing a place like Joubert Park after apartheid? What is at stake in the deployment of a postcolonial picturesque idiom? Waiting assumes a different kind of space to a space in which one spends only limited time. The photograph clearly is a polemic against the idea of a decaying park and it makes references to European landscape painting. This is a new kind of appropriation of the park, by a black (queer) person, and it could be read as an expression of both despondency and hope.

- Jonathan Cane is an art historian and a postdoctoral fellow at the Wits City Institute, Wits University. He works on the ecologies of modernist planning in post-mining landscapes, histories of high-rise building and genealogies of concrete in the global South.

- Sabelo Mlangeni’s photograph A space of waiting is this issue’s cover image.

Alfred Crossberg (he anglised his name which was Kreutzberger) of Beuthen., a German Jew who fled from Berlin in 1936 and set up his photographic business in the Empire State Building. He married an English woman Mary Underhill and they lived in Joubert Park. I have written a book on the life of Crossberg, and was by him when he died aged 96 years. We then both lived in Cornwall, England. I now possess his entire photographic collection.

WOW, where can one enjoy viewing Alfred’s photographic collection?