The JRB presents the winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

Egyptian writer Adam El Shalakany won the prestigious award this year for his story ‘Happy City Hotel’. Kenyan writer Noel Cheruto’s ‘Mr Thompson’ was first runner-up, and South Africa’s Lester Walbrugh’s ‘The Space(s) Between Us’ was second runner-up.

The following stories were highly commended by the SSDA judges: ‘Why Don’t You Live in the North?’ by Wamuwi Mbao (who is an Editorial Advisory Panel member and regular contributor to The JRB), ‘Slow Road to the Winburg Hotel’ by Paul Morris, ‘Outside Riad Dahab’ by Chourouq Nasri, and ‘The Snore Monitor’ by Chido Muchemwa.

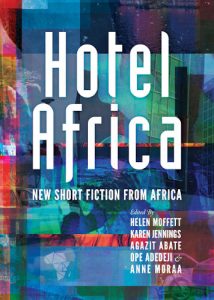

The prize is worth $800 (about R10,800) and open to any African citizen or African person living in the diaspora. All twenty-one longlisted stories are contained in this year’s SSDA anthology, Hotel Africa: New Short Fiction from Africa.

SSDA counts among the most esteemed writing organisations on the continent. Two stories from the 2013 anthology, Feast, Famine & Potluck, were shortlisted for The Caine Prize for African Writing, with that year’s SSDA winner, Okwiri Oduor, going on to win the award. Terra Incognita (2014) and Water (2015) received wide critical acclaim, while two stories from last year’s anthology, ID: New Short Fiction From Africa, were recently shortlisted for this year’s Caine Prize: ‘All Our Lives’, the SSDA winning story by Tochukwu Emmanuel Okafor, and ‘Sew My Mouth’ by Cherrie Kandie.

Read on, and enjoy:

~~~

The Space(s) Between Us

By Lester Walbrugh

2nd runner-up of the 2018 Short Story Day Africa Prize

Early spring, a Monday morning, and she had died in the night. Just like that. No goodbye. No see you later.

He recalled a friend who one day coughed up blood as he was about to leave for school. The boy struggled to breathe, they said. He left red streaks on the walls as he stumbled through the house, arms outstretched. When the whole family were sufficiently horrified, he dropped down dead in front of them.

‘That white hotel in Arniston, Terence. Take me there,’ he heard her say, but found her eyes closed. Her body next to him was as still as the air in the bedroom. The clarity of those words lit up his thoughts, which came clear and fast, one on top of the other. For the rest of that day, they steered his actions.

I need to book a room. Pack a bag. I have to get a car.

With his heart pounding and his face numb, Terence slipped his legs over the side of the bed. He plonked his tog bag next to her. He rummaged in their closet, grabbed his best Adidas top, pulled it over his head. It smelled musty and a little sour, but tolerable.

Her side of the closet was neat. She had strewn the shelves with dried rose petals that picked up the colour of the polka dots on the curtains and the stripe at the edge of the duvet. Their bedroom was her pride. When his brothers visited, she would usher them and their jealous wives through the living room to it, pointing out a new set of linen or a curtain that matched the rug. ‘It looks like a hotel room! So nice,’ they would say. But when she turned her back, they rolled their eyes at one another and later, at the car, they’d whisper to him that she was too proud, trying to be something other than what she was. Somehow better than the rest of them.

The bag was packed. It held their jackets, a change of underwear, and socks. He dressed her in a loose-fitting summer dress, the one she always wore to the beach.

His mind left him and raced up and down the township street, knocking on each familiar door, crossing off his options for help.

His uncle.

He locked the front door, brushed the creases from his top, then strode to the top of the hill to rap on the blue door, three times, with evenly spaced pauses. His uncle parted the curtains and squinted at him through the window. Terence stepped into the glow of a naked bulb above the door, and hoping his face did not betray him, he asked his uncle for the car, offering to bring it back the following day. He would guard it like it was his own. He would check the oil and water, wash it and—as an afterthought that sealed the deal—promised to return it with a full tank.

The car sputtered down the road, dodging a dog and the pothole puddles left after a night-time shower. The mountains around the village were smudged against the last dark of the night, their outlines hardening with each increment of light. In the frosty silence of that early morning, the street was stirring. People trudged down the hill.

He bolted into the house, leaving the car idling.

A beanie. Sunglasses.

He propped a large pair of sunglasses on her nose and drew the black beanie over her head and ears. She would go in the passenger seat, and the bag in the back; if they were pulled over, this would raise the fewest questions. He grabbed the bag handles, then scooped her up in his arms. She’d grown heavy; two cases of beer.

He shuffled to the idling car. He tried the passenger door handle and whispered an exasperated fokkit.

It was locked.

He considered draping her over the bonnet while he unlocked the door, but returned inside instead to lay her back on the bed.

On his second attempt, he managed to strap her into the passenger seat. The streetlight flickered onto a few familiar faces in the crowd passing by the gate. But it was too early, too cold, and they were on auto-pilot, looking straight ahead.

As Terence slid in behind the steering wheel, the first rays cleared the mountains. A delicate warmth spread through his body. Tyres spun, spitting gravel before they found traction on the tar.

At the intersection. Two minutes. Three.

A hoot from behind. In the rear-view mirror, a truck bore down on them, and in a gap on the freeway, he turned left.

They hit the speed limit. He glanced over. Her hand had slipped to her side, and he returned it to her lap.

Their world consisted of their house, their street, the village, and the fruit farms with their packing sheds, which, like most of their jobs, went into hibernation for the winter. Cars on the national road sped by, oblivious to their existence and on their way elsewhere, warmer, with a beach and restaurants and hotels with staff in crisp uniforms. When they were kids, there was a comfort in the smallness of the village. The postman passed your house at the same time each day; you looked up from whatever you were busy doing to wave at him, and everyone was your neighbour.

For its size, and its distance from the next nearest town, the village was filled with a vague sense of other but, like all children shaped by a well-defined community, they were also bound to its fears and attitudes. The village moulded them into tiny people and, like Sunday lunch jelly, they tended to shiver once exposed to the outside.

Previous generations had never been to a restaurant; much less did they comprehend the rituals of staying in a hotel, and they were therefore ill-equipped to carry this type of experience onto their children. The past had already proved that walking through the wrong door, one reserved for others, could get you thrown out, humiliated, arrested. What if you said something wrong and they misunderstand you? What if you took the wrong chair? Ordered the wrong meal? The experience loomed as terrifying as a first day at school. So they simply passed on these feelings to their children instead.

During the summer holidays, Terence and his friends took these lessons and came to know where they belonged and where they did not. Come December, once the farms had shut down, their families would make the drive to Arniston, a fishing village dangling from the edge of the continent, and along a rocky stretch of coast they would pitch their tents at a campsite with a tiny café stocking essentials. There was no electricity, but there were hot showers and naphthaline toilets. Their designated swimming beach was a walk further south, down the road, past the hotel.

The Arniston Spa seemed designed for other people, wealthier, worldlier. It sat atop a slope that ran down to a pretty cove, with a chainless anchor leaning, lost, on its manicured front lawn. On weekends, swarthy cars pulled up to its whitewashed doors, spilling onto its terrace guests in dark sunglasses. Three storeys high with a flat, balconied façade, it whispered luxury. The east-facing building was as white as the fishermen’s cottages to one side, and in the morning they all glimmered in the sun.

Each fading day, their group would pass the Arniston Spa on their way back from the beach, towels draped around their shoulders, shivering like skeletons. Curiosity occasionally prompted the children to act as if they were guests at this grand hotel. They would lock arms and mosey up its driveway with long strides and puffed-up chests, noses held high, giggles suppressed. Their play-courage never took them all the way to the entrance. At the last second they would turn and scatter back to the road, where they clutched their middles laughing, their exhilaration propelled by the release of a new fear.

As they took hold of themselves again, she alone would grow quiet in the midst of their chatter, stealing glances over her shoulder at the retreating hotel. Terence never understood the dip in her mood, neither had he the means to question its significance, and in time he forgot—until that morning.

It will look suspicious if I carry her in.

A wheelchair. He would have to wheel her into the hotel.

There were supermarkets, petrol stations, and a clinic lined up in Bredasdorp’s main road, the last town before Arniston. Terence considered the disability parking spaces in front of Pick n Pay. Maybe, under the guise of offering help, he could make off with a wheelchair. But he let go of the idea.

The clinic.

He reasoned it would be better to approach a nurse at reception, request a wheelchair for a patient in his car, then load it into the boot and drive off. And that is just what he did.

Because Terence was invisible to her. She could not see him, had not seen him for a while, so it was easy for him to be a phantom of some sort, even while talking to someone. Afterwards, searching for the missing wheelchair, the nurse would have had trouble recalling their conversation, would doubt herself that he had even been there.

With her, with each passing day, he had learnt to play small. He had shrunk. Don’t sit on the bed, you’ll crinkle the linen. Don’t come in here with your dirty body and your stinky feet. Don’t show any presence of you, anywhere.

Bredasdorp was at their back. Big, cumulous clouds followed them to the ocean. Terence felt a breeze on his neck, as if from a soft, expelled puff of air, and rubbed the skin there. Her neck was also exposed, and he picked at the round collar of her top. His hand brushed her chin. He felt its cold, congealed muscle and recoiled.

‘Almost there,’ he said.

In the wheat field beyond, a blue crane raised its neck.

He dropped his chin. His eyes bore into the road. His mind drifted. The evening returned in snippets. He had gone to bed early. She had finished the last beers with two of her friends in the other room. The music was Saturday loud, but her ridicule of him was louder. In their tiny house, it was deafening, and he lay awake on his side, listening.

‘No, what does he know? Scared of people. Can’t get a word out. You know we only ever go to eat at the Spur? Says he doesn’t like the food at the other places, but no, it’s because he’s too scared. English? Forget it. That’s why we’ll never go anywhere, he can’t even say to go somewhere nice for the weekend. Shame. I must just get myself a sugar-daddy. From Cape Town.’ She had laughed until the tears rolled. Her laughter grew louder until it poured from his ears, coming at him from every angle, and he had opened the windows to let it out.

After her friends had left and she had fallen into bed, he rolled onto his back and said to the ceiling, ‘Did you have fun tonight?’ She uttered a low moan, as she had taken to doing, as if her breath was too precious to waste on him. He had a habit of shrugging off her indifference, but it hit him like a mallet then.

So quiet now, he thought. Her lips, usually wet and pouty, were grey. A faint smear of freckles he had never noticed before lay across her cheeks.

The car chugged over a hill, then plunged onto a long, grey stretch of tar. The fynbos parted. Arniston shimmered into view. He slowed and their clouds raced out to sea.

Leave her in the car. Check in. Settle the bill later.

He left her in the car while he checked them in, leaving his driver’s licence as security, and agreeing to settle the bill upon check-out. When he rolled her past the front desk, the staff smiled into the void between them. They met no one else on the way to their room.

Hours later, on their balcony, he stuck out his tongue to taste the air. A late-afternoon breeze tumbled with mists of sea spray. He sat with her clenched hand in his, a glass of beer in his other hand. The hotel shadow stretched across the lawn, creeping over and past the anchor down to the cove with its strip of sand, the grains at their brightest and sparkliest in the moment before dusk. For a while, Terence studied the languid waves tumbling onto the beach.

They had got married in a small ceremony. Afterwards, there was a party at a friend’s place. There was music. There was beer. They braaied, and there was laughter. In the midst of it all she looked over at him, over the crowd, and in her smile Terence saw how much she loved him. How much of him she saw. He had held onto that smile for five years. It had since degenerated into scowls and sneers with each successive failure on his part—failure to find a permanent job, and their having to move house every few months. At their wedding, in his vows, words he had caught in that indefinable space between his body and his soul, he had promised her the world. And since, he’d given her nothing more than a room to drink her beer in.

‘I’m thirsty.’

He brought the glass to his lips and sipped from it.

‘I am thirsty. My fok.’ It was both an order and an admonishment. He swung his head around, expecting to see her dark eyes on him.

He took another sip.

‘I am thirsty. You getting married to that glass?’

What was her problem? He had brought her to this nice hotel. They were sitting on the balcony—Look! There’s the anchor!—He was drinking a beer, yes. They were alone and enjoying each other’s company. Now she wanted to come and spoil it with her demands, again. Only demands. Why is she talking to him? What is it with her? He was never good enough for her. He never matched her bedroom, her bedding, the curtains—

‘I am cold. And I am hungry. I am thiiiirrrrsty.’

Fokkit. Terence jumped up, locked the bathroom door behind him. He fumbled with the taps, knocked them about, twisted the fancy knobs this way and that. Fokkit.

‘Terrreence. Thiiirsty! Huuuungry!’

Fokkit, he thought. If she wanted beer, he would get her some. She would drink. And she would eat. He would feed her. He would pour beer down her throat, as much as she wanted, as long as it shut her up.

Dinner. Beer. Fish and chips.

Finally, he managed to get the tap running, splashed his face with cold water, then returned to the balcony. She sat etched against the pink sky and, for a moment, tenderness grabbed him. But he shook his head. There were things to do.

The dining room was empty save for an elderly couple seated near the fireplace. Two waitstaff were idling about at the entrance.

He adjusted her sunglasses, then rolled her into the restaurant.

‘Table for two?’

‘Yes, please.’ He took a deep breath and gestured to the wide windows framing the front lawn and its anchor. ‘Can we sit next to the window?’

The waiter brought menus.

‘Two beers, please,’ he said.

‘Castle or Black Label? We have craft beers also. On tap.’

‘Craft b—? No. Black Label. Dumpies, thank you.’

The beers brought, he looked about him and seeing the staff distracted, reached over, grabbed her bottle of beer and guzzled half.

The waiter again.

‘Two fish and chips, please.’

The waiter scampered off to the kitchen.

‘Terence, I want praaaawnnnns.’

He flushed and looked about to see if anyone had heard.

The other waitress was at the bar. She had a hand cupped over her mouth, talking to the barman, both looking their way. It’s nothing, he thought. People gossiped all the time. What did he expect in a place like Arniston, where at another table sat only an old greying couple, as old and grey as couples get—nothing to see here, move on—but they, fairly young, on a Monday? He knew they did not look like typical guests. You could tell by the way their clothes fit, by the tense expectation on his face and the grave grimace on hers, that their place was in the kitchen, or outside, tending the garden, but here, dining in the restaurant?

He took her hand, brought it to his cheek and mumbled, ‘Nice weather.’ He imagined it was what people talked about in these hotels.

Faint, bell-like laughter drew his gaze out the window. It came from a group of children ambling by. They were dark from the sun. They were playing tag and teasing one another, paying no attention to the hotel, but as they passed through its shadow, their laughter faded. Some pulled their towels tighter around their shoulders. After a few strides, they stepped back into the sunlight. Their jumping resumed. One boy bellowed louder than the rest.

A bath and an early night.

He pushed back his chair and left her to contemplate the view. Their waitress flinched as he stole up behind her, asking to take the meals to their room instead. Yes, take-away containers are fine. No, they won’t need any sauces, thank you. On our tab, yes.

‘My wife is feeling a bit under the weather, and has lost her appetite,’ he said—and believed it. He had to believe it. The best lies are laid to rest the moment they leave your lips. They have neither a past nor a future. That moment, Terence had a simple faith, that whatever he did would be true and real and just. He rolled her past the waitstaff back to their room.

He ran a bath and got into the tub first.

What now? Where to now? Then, suddenly, and more pressing: what if people find us? Will they kick us out? His fears were irrational. They were paying guests, not some laaities who were chancing their luck, acting as if they could sleep in these beds and enjoy the views from the balcony.

Her joints had stiffened, and being seated in the passenger seat and in the wheelchair had locked her in this position, bent at the hips and at the knees. He mumbled words of gratitude for dressing her in the easy summer dress. He slipped her body into the tub. He wiped her body with a cloth, and the warm water returned the colour, a deep brown, to her skin. Soap bubbles converged on her toes then slid down her feet, revealing the red paint on the tips of her toenails. Despite his care, she shifted; her mouth, then her nose slipped under. She stayed submerged until he looked up and noticed; he grabbed her head and pulled her face back to the surface.

Then her body was clean and he was calm. He carried her to the bed, laid her upon the towel he had spread out, dried her steaming body from head to toe, and towelled her hair.

During the night he turned, unable to sleep. Her snoring had kept him awake for five years and, that night in the hotel room, her silence did it just as expertly. He threw his legs over the edge of the bed, made his way to the bathroom to pour a glass of water, then took the chair next to the bed. The moonlight drenched their room in the dark blue of the sea; the bed, the cupboard and the walls seemed sheer, veils to a place beyond the hotel room.

She was on her side, barely lifting the sheets. It was as if she wanted to leave the linen undisturbed, as if by morning any sign of her presence needed to be erased.

The pre-dawn chill was still lingering when he wheeled her through the lobby and out the front door, with the night manager at the reception desk engrossed in her phone.

It was a smooth ride down the path, curving past the anchor and crossing the road to the eight steps that led to the cove. There he engaged the brakes of the wheelchair.

He carried her down to the sand.

The sea was swaying from side to side.

Terence removed her jacket, slipped the dress over her head, rolled the socks from her feet. He undressed to his briefs.

He entered the orange ocean with her in his arms and walked towards the horizon until the water lapped against his slow-beating heart. Shadows tightened and loosened over her body. Sea water trickled in and out the corners of her mouth. He lowered his arms.

After a while she started sinking.

He had to leave her there, or she would never go.

She was drowning and he could not save her.

~~~

- Lester Walbrugh is from Grabouw in the Western Cape. His work has appeared in the Short.Sharp.Story anthology Die Laughing, the Short Story Day Africa anthology ID, and New Contrast. He has lived in the UK and Japan, and has since returned to his home town to work on a collection of short stories and a novel.