The JRB presents the winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

Egyptian writer Adam El Shalakany won the prestigious award this year for his story ‘Happy City Hotel’. Kenyan writer Noel Cheruto’s ‘Mr Thompson’ was first runner-up, and South Africa’s Lester Walbrugh’s ‘The Space(s) Between Us’ was second runner-up.

The following stories were highly commended by the SSDA judges: ‘Why Don’t You Live in the North?’ by Wamuwi Mbao (who is an Editorial Advisory Panel member and regular contributor to The JRB), ‘Slow Road to the Winburg Hotel’ by Paul Morris, ‘Outside Riad Dahab’ by Chourouq Nasri, and ‘The Snore Monitor’ by Chido Muchemwa.

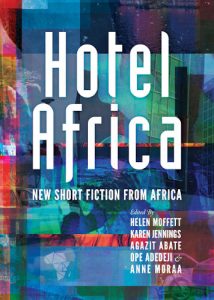

The prize is worth $800 (about R10,800) and open to any African citizen or African person living in the diaspora. All twenty-one longlisted stories are contained in this year’s SSDA anthology, Hotel Africa: New Short Fiction from Africa.

SSDA counts among the most esteemed writing organisations on the continent. Two stories from the 2013 anthology, Feast, Famine & Potluck, were shortlisted for The Caine Prize for African Writing, with that year’s SSDA winner, Okwiri Oduor, going on to win the award. Terra Incognita (2014) and Water (2015) received wide critical acclaim, while two stories from last year’s anthology, ID: New Short Fiction From Africa, were recently shortlisted for this year’s Caine Prize: ‘All Our Lives’, the SSDA winning story by Tochukwu Emmanuel Okafor, and ‘Sew My Mouth’ by Cherrie Kandie.

Read on, and enjoy:

~~~

Happy City Hotel

By Adam El Shalakany

Winner of the 2018 Short Story Day Africa Prize

There lies on Mohamed Farid St, in Abdeen, a formerly upscale district of Cairo now fallen on hard times, a hotel inaptly named the Happy City Hotel. It’s squeezed between two dilapidated buildings, one of which houses a butcher on the ground floor, and the other a mechanic’s shop. All around the hotel, the stench of the city, its dirt and sweat and blood and semen and shit, rises up with the dry desert heat. The overstimulation in the city turns the constant blare of passing klaxons into a synthetic silence.

The streets are simultaneously dark and over-lit. Busted street lamps hang overhead, but the neon lights of shops, cafés, hotels and bars line the street with a dull, aggressive buzz. The buildings stand up next to one another, without space to breathe or escape between them. Brick building after brick building, interrupted every once in a while by history, now invisible and forgotten. Of all the lights that buzz, there is one that flickers a weak red: ‘Happy City Hotel’, a home to many a patron and a story.

If you enter the hotel, you must pass through a rusty, non-functioning security door, whose purpose is not to protect, but to remind you of the shallow menace of tyranny. A security guard sleeps peacefully at an old wooden desk to the side, his head resting on his fist. Through the threshold, past a fake garden filled with ceramic turtles, is a small, tight ascenseur, that goes up to the rooftop bar, the sole attraction of the Happy City Hotel.

Alcohol is forbidden in Egypt. Haram. And yet it’s not. Bars do exist with a special licence, which are expensive to get. A bureaucrat will accept a bribe for most things. A bribe for a liquor licence? Never! Unless you make it double, like the scotch.

Hotels get a liquor licence automatically. And, unlike the rest of the world where bars are attached to hotels, hotels in Egypt are attached to bars. The Happy City Hotel is a shitty hotel, but it’s got a bar, and a bar means it’s got clientele. So, on the seventh floor of that shitty hotel, there is a rooftop bar, which pays for the whole damn thing. Men and women, foreign and domestic, old, young and in between, sit scattered in their own thoughts, sipping at green glass bottles of Stella beer.

A fat man in the corner of the bar looks down into his bottle of beer. His back is to the railing, behind which downtown Cairo, the City Victorious, extends into the distance. The tops of buildings zig-zag like a wave frozen in time. Beyond the buildings and far in the night is a distant ridge which looms above the rolling wave like the crest of an oncoming tsunami. The tsunami is Mokattam mountain, which Saint Simon the Tanner split, and on which sits Muhammad Ali’s mosque. On that mountain once stood Napoleon, Horatio and Suleiman the Magnificent. Many men and women died there for God and glory, with sword and shield, horse and musket.

With his back to history, Hamdi only has eyes for his bottle, for escape. He is round and portly, though not joyfully so, nor does he look weak. There is muscle beneath the fat. Clean-shaven, most likely a government employee, not too tall, not too short and not bald, which is uncommon in Egypt. Aside from his hairline, he resembles most men his age. Hamdi: a common name for a common man. He looks at his drink, the reflection beaming back at him from the bottom of the bottle, a distorted, detracted image of himself. He likes to think that the portly man in the reflection is only fat because of the curvature of the glass. He knows he is wrong, but he prefers the alternative to the truth.

He was once a fit, young man. He was born around the corner, the son of a public notary and a housewife. One of five siblings, he was left to fend for himself. And so, he learned to be a boxer. Strait-laced, sharp body of muscle, square-jawed, with no imagination in style or soul. He shadowboxed in the sixties. Swooping in and out of the light, fighting the shade that loomed larger than life in front of him, and which sparked from the street outside his bedroom window. A pillow hit him in the head. His brothers trying to sleep, kept awake by the sound of imaginary fights. They told him to stop, that he would never amount to anything.

‘If you don’t shoot for the moon, you’ll never end among the stars,’ was what he told them. ‘I’ll box Muhammad Ali one day.’

They laughed. ‘You don’t know this world,’ they told him.

At seventeen, one year before the Rumble in the Jungle, Hamdi broke his jaw. His coach had told him that he wasn’t ready, but Hamdi pushed to get in the ring. He shot for the moon, and instead landed head first on the mat, spending a month in hospital, never to box again. Never to be thin and fit again, either.

Still, he had had one solace. The hospital had been full due to the war, so they placed him in one of the private wards. There had been a black-and- white TV in the room, a TV that his family couldn’t afford. There he spent the month falling in love with cinema. He left the hospital, dreaming of scriptwriting and directing.

But time makes fools of us all. His dreams were put aside when he fell in love with a beautiful girl and married her. Marriage and children forced him to work, and thoughts of spotlights, whether in the ring or behind the camera, melted away.

Now he finds himself old, sitting on a rooftop reflecting on his reflection in a little green bottle. Waiting to be young and free once more. Waiting for a woman, who is not his wife, whom he has met online. She will wear a rose.

Marie, John and Shady sit at the table next to Hamdi’s. Shady has his back to the railing. Marie, if she were to look past him, would see the Cairo Central Bank down the road, but Marie only has eyes for Shady. They are all in their twenties, poor in pocket but not in ambition. They sit hunchbacked and nurse their beers, aiming to make them last as long as possible. Shady is a handsome young Christian man who works as a clerk in a law office. Christians in Egypt are hard pressed, and tend to intermarry to preserve the faith. Marie, being a good Christian, wants Shady as a husband. She is also deeply attracted to him; she would want him even if he were Buddhist. She loses herself in his eyes, in the cologne he wears, mixed with the smell of tobacco bitters, deep and musky.

John is less handsome than Shady, and has eyes for Marie. He doesn’t see past her to the plaster cast of Horus placed on the cheap and tacky walls of the Lotus bar. He has a hookah pipe in his hand, but barely smokes. He hates smoking, but if he didn’t smoke and he didn’t drink, they—Marie the angel and Shady the devil—wouldn’t invite him out. John has learned a difficult lesson in life, that good company gets harder to find the older you get, and beggars can’t be choosers.

John is an English teacher at a public school. He speaks horrible English, and if he is being honest, knows very little about the language. He became a teacher by accident, not by design. He had done well at training college and went where the State placed him. Then his uncle, who happened to be the nazir of the public school John would end up working at, told him that there was a vacancy for an English teacher, and that John should apply.

‘But make sure that you prepare!’ his uncle had warned him.

John did. He trusted his uncle’s vision blindly. After all, didn’t ‘nazir’ mean both school principal and visionary? John tried to decipher the strange language by reading poetry, and fell upon a snippet that reminded him of Marie, although he understood next to nothing of it. He decided to memorise it:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths, Enwrought with golden and silver light, The blue and the dim and the dark cloths Of night and light and the half-light, I would spread the cloths under your feet: But I, being poor, have only my dreams; I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

And when he recited it, poorly, to the interviewer at the Ministry of Education, he was given the job even though, at the time, he had been thinking of Marie. He took this as a sign that his love for her was blessed.

This leaves Shady, whose back is to the world and who only has eyes for John. He will end up marrying Marie, and Marie will spend her days in friendship with John, and her cold nights lonely, in bed with Shady. An almost happy ending where everybody gets what they want, but in the saddest way, like an ifrit’s curse. John will finally recite the poem to Marie on his deathbed, long after forgetting about the cool-breeze nights on top of the Happy City Hotel.

‘Maître! Beer!’ calls a man from another table, and the maître d’, Khaled, stands at attention. Because he’s the bartender, he can wear whatever he wants. If cleanliness is close to godliness, then he is in hell. But hell pays, and the pious are poor. A man of thirty-plus, Khaled is still unmarried. He has fucked before, so he isn’t a virgin, like half the people in the bar. In fact, he had a quickie once in one of the rooms below, in the bowels of the empty hotel. A john had brought a hooker and rented a room for the night, but he had left early. She had come up to get a drink, and had started chatting with Khaled.

‘Maître! Beer!’ the barfly calls again. But Khaled can’t hear him. His mind is flying back to that night four years ago when he was twenty-eight, ignorant of the world. The barfly, who hasn’t flown back into the past with Khaled, is still ignorant of the world. One of the holiest shrines in all of Shia-dom, thrumming with spiritual power, lies directly behind him, but he is focusing only on his parched throat. This is a shame, because if the barfly chose instead to descend from the bar of sin, walk through the crowded Cairo night, wind through the ever-tightening alleys until reaching El Hussein, and then prostrate himself before the head of the Prophet’s grandson, he would find a ten-pound note dropped on the ground.

‘A beer please,’ the woman had asked Khaled politely. She was veiled, with a colourful hijab wrapped around a round face. Almond-coloured and shaped eyes looked back at Khaled as she arched forward, not at all demurely. Khaled had fallen for her at that moment, but he hadn’t known it yet.

‘You’ve got hair showing,’ he said, pulling out a beer for the woman who he later learned was named Mariam. A small black curl wound its way down her face. Instead of placing the hair back beneath her veil, she twirled it.

‘So, you’re a whore?’ He had been raised to hate sex and women, and asked the question honestly, if a little maliciously. The smoke of roasting coals used to grill kebabs had stuck to his shirt. A greasy, heavy scent.

‘You’re a barkeep?’ she asked in return. They both worked in sin, and what of it? The greasy, heavy smell had become a greasy, heavy feeling as he talked to her in between bouts of serving the clientele.

Finally, he didn’t know how, they had found themselves in a room two levels down, fucking. He was a virgin, but later that night he was an experienced man. He fucked with his back to the wall. Behind it, and a few buildings down, was the Jewish Temple, one of the last remaining operating temples in Egypt. It had been deserted after the wars, including the war of ’67 in which Shady’s uncle had died like a dog in the desert. Shady’s uncle had also been gay, but he hadn’t lived long enough for it to cause him or his family much bother.

When Khaled had finished, he began to cry. He had fallen in love with a whore. Mariam stared back at him with innocent eyes. He slapped and beat her, and she ran out of the room and out of the Happy City Hotel forever.

‘Maître! Beer!’

With a heavy heart, Khaled walks over and slams a beer on the table. Fucking sinners. The greasy, fatty scent of roasting kebabs still wafts in the air, but now the smell makes him feel sick.

But not Lamia. She is a student and made of fire. A communist at Cairo University. She has been told not to drink, not to laugh, not to smoke, not to fuck, not to swear, and not to dress the way she does. That is why she does all these things. The guys love Lamia and take her to the top of Happy City Hotel. The guys don’t have to pretend around her. They are all in engineering school and they can drink and swear and joke in front of her. She is fun to be around, even if she is crazy. She has short hair, cropped in pain.

She hasn’t always been made of fire, but she has always been different. When her girlfriends wrap their heads in fabric, Lamia leaves hers uncovered. When others follow obediently and pray, Lamia does not. Still, she always thinks of herself as a good girl, even if she knows others don’t see her the same way. She has always been a string singing without a harmony. Alone in a dark universe where the blind follow the blind.

When she’d first gone to university, there’d been one professor who was young and rash and beautiful. He would stand in front of their class and insult the State and God. People hated him, but Lamia was ensorcelled. His glasses, his chalk-stained hands, even his linen Nehru shirt. His name was Abdelwahab, like the singer. But this Abdelwahab’s voice was a far cry from the deep, sonorous sound of his namesake. His voice was nasal and whiny. But Lamia didn’t care. She was in love, and she told him so, and he swallowed her up.

They went out for coffee and read treatises and kissed and fumbled beneath one another’s shirts. All in secret, until one day Lamia wanted to break the taboo and fornicate. She didn’t call it that, but that’s what he heard, and it scared him. To the bone. He told her that he couldn’t take her hymen. Inside him, instead of fire, was ice—freezing terror. But that night Lamia, terribly practical, took a cucumber to her hymen, removing the professor’s obstacle. She rushed to him the next day and told him what she had done. He never spoke to her again.

Lamia, in her fury, shame and guilt, chopped off her hair. Now she hangs out at the top of the Happy City Hotel, her fire lighting up the night. Stepping out of the white taxi with a meter that doesn’t work, is Hamdi’s wife. She pays the driver a few guineas over the normal price; she feels like splurging. She is dressed in her Friday finest. A not-too revealing dress, loose and black to hide her growing curves. She walks into the Happy City Hotel, through the broken door and past the sleeping security guard. If the guard had been awake, he would have seen that the black of her dress was seductively broken by a bright red rose.

~~~

- Adam El Shalakany lives and works as a lawyer in Cairo, Egypt. He studied political science in Canada, and law at the School for Oriental and African Studies in London. He has loved writing ever since he was as tall as a hookah pipe. This is his first published short story.

Simply beautiful writing

Excellent