This August marks one hundred years since the birth of Noni Jabavu. Makhosazana Xaba reflects on the life of this legendary writer: a woman of words, and a citizen of the world.

‘Noni Jabavu returns home’ is the title of a biographical fragment I wrote during the first semester of my MA at Wits University in 2004. Noni was a woman of words, and a citizen of the world. In order to write this first essay, I created a chronology of her life which, over the years, became longer as gaps were filled. The research and writing journey is finally coming to a close, albeit with the acceptance that some gaps will remain, because some stories refuse to be told.

This year South Africans celebrate the centenarians, our foundational writers and Noni’s peers: E’skia Mphahlele, Peter Abrahams and Sibusiso Nyembezi. Here, I present a writerly-outputs version of Noni’s chronology as a way of celebrating her words, the writings that catapulted her into the public imagination in many countries of the world.

Chronology of Writerly and Creative Outputs—Noni Jabavu

- 1919: Born Helen Nontando Jabavu on 20 August, Alice Cape Province

- 1942–1963: Freelance broadcaster for British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Radio

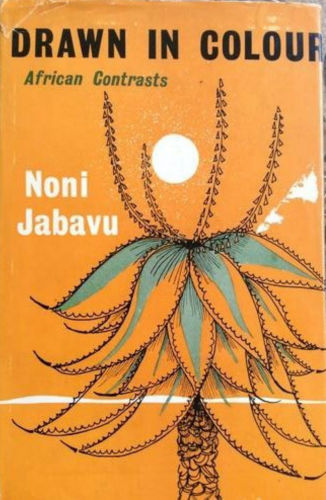

- 1960: Her memoir, Drawn in Colour: African Contrasts, published by John Murray in London

- 1961–1962: Editor at The New Strand magazine in London (December 1961–March 1962)

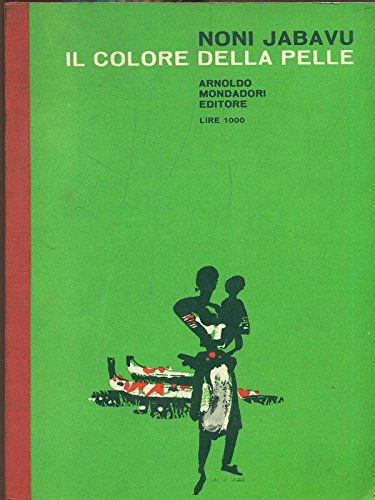

- 1962: Il colore della pelle, an Italian translation of Drawn in Colour, published by in Italy

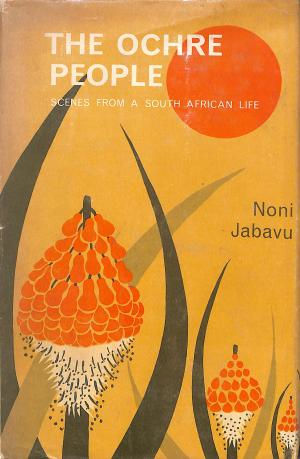

- 1963: Her second memoir, The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life, published by John Murray

- 1977: Weekly columnist for the Daily Dispatch newspaper (Eastern Cape, South Africa) ‘Noni on Wednesdays’

- 1982: The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life published by Ravan Press in South Africa

- 1980–1987: Wrote on and off for The Herald newspaper (Harare, Zimbabwe)

- 2008: Died on 18 June at Lynette Elliott Frail Care Home in East London, Eastern Cape, South Africa

The Amazwi South African Museum of Literature (formerly the National English Literary Museum—NELM) was the first museum I visited, in 2005, to research Noni’s life. It made possible my initial understanding of her life trajectory, and I was then able to plan a series of international research trips. In 2007, I undertook trips to the United Kingdom, Jamaica, Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe; and in 2018, while on a trip to the United States, I was led to an archive in Newark that has useful material: correspondence between Noni’s father, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, and Lida Clanton Broner, an African American who had visited South Africa in 1938. All told, in the various countries I sourced information from a total of nineteen archives, libraries and museums.

I have read innumerable biographies, creative non-fiction and history books on the countries where Noni lived. The most enduring impression I received from my research, however, is that being a writer does not guarantee that you will end up in the archives of countries that are not your own. I have also learned just how subjective the choices are, when it comes to who lands up in an archive. These two topics, of course, are for longer and detailed pieces.

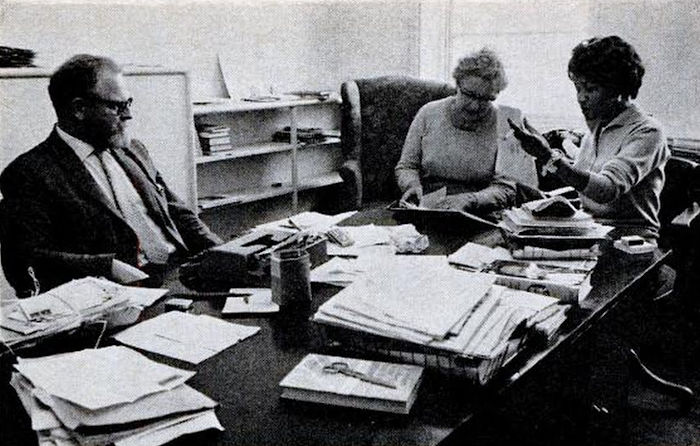

To date I have written and published a range of biographical fragments and articles, including an MA thesis, Jabavu’s Journey, accessible at Wits University. Here is a short excerpt from the thesis, covering Noni’s time as editor at The New Strand magazine. She was forty-two years old when she began her editorship, and Drawn in Colour had been reprinted five times.

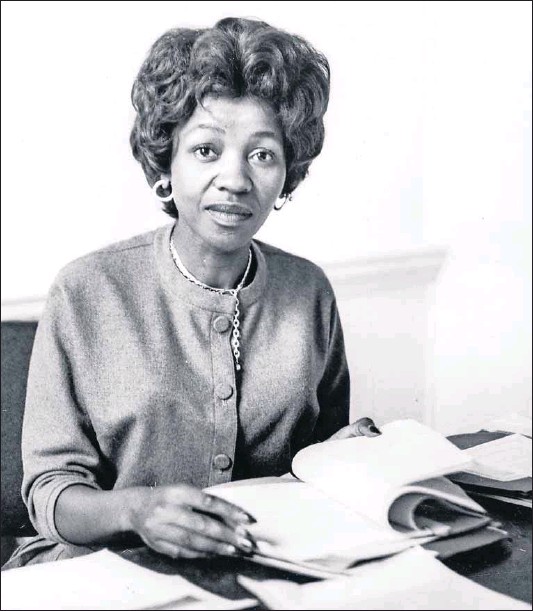

The publication of her first book made Noni a public literary figure. The case of a black African woman, a British citizen by marriage, being published by a mainstream publisher so long before the advent of a distinct, feminist British women’s press that only began in the eighties was certainly an oddity for many a Briton. Editorship at The New Strand marked her first executive position and her first position in publishing. She distinguished herself as a groundbreaker by becoming the first black as well as the first woman to be editor of this prestigious magazine. In 1951 she had married Michael Cadbury Crosfield, an upper middle class British filmmaker with whom she lived in Uganda until she returned to England to take on the job at The New Strand. To those who knew Noni’s family history her successes were merely a case of an apple falling close to the tree.

The original The Strand magazine (1891–1950) founded by publisher George Newnes became one of the best known and most read monthly magazines of the twentieth century. […] In the UK The Strand soon became a trendsetter and one of the most popular fiction magazines renowned for great contributors of the time including: Grant Allen, Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Graham Greene, O Henry, Anthony Hope, Rudyard Kipling, AEW Mason, E Nesbit, Leo Tolstoy, HG Wells and PG Wodehouse, to mention but a few. Even Queen Victoria and Winston Churchill are known to have contributed to The Strand at different times. During the World War II, The Strand, like many entrepreneurial entities, suffered. Costs rose and circulation fell. The magazine never recovered. By 1950, the magazine needed a quarter of a million pounds to put it back on its feet. The owners lost hope of raising the money. In March 1950 The Strand was forced to stop publication.

The press was agog with announcements that the old The Strand magazine would be revived under the new name The New Strand and that Noni would be at its helm thus joining the ‘august ranks of London’s editors’. She would be walking on the illustrious path paved by the magazine’s former editors: Herbert Greenhough Smith (1891–1930); Reeves Shaw (1930–Sep. 1941); RJ Minney (Oct. 1941–Dec. 1941); Reginald Pound (1942–1946) and; Macdonald Hastings (1946–1950). Noni made history by being the first black and the first woman to become an editor at The New Strand. As she had been born in South Africa her British citizenship was an acquired one. Interestingly, she openly disliked the short story genre, a genre that was a distinguishing feature of the magazine. ‘I don’t like short stories,’ (From The Editor’s Desk [FTED], December 1961, p. 69) she wrote in her first editorial column but had taken the job anyway. Why?

Noni had crystal clarity about the writers she wanted to attract, the changes she planned to introduce. The challenge seemed to be her driving force. In the first editorial of the issue that came out in December 1961 she wrote,

‘The New Strand that is in my mind’s eye is a platform for men and women who today wait in the wings of public life because they are young and therefore not yet prominent; but being young, vivid, racy, up-and-coming count and will do so in five, ten, fifteen years’ time when the rest of us won’t amount to a row of beans.’ (FTED, December 1961, p. 69)

In commemorating Noni’s centenary I share the list of published biographical fragments that I wrote over the years for readers keen to learn more. Noni’s life offers lessons about black women of her time: how she navigated her life as a teenager in the nineteen-thirties in South Africa and the UK; how World War II affected her life; how she wrote about her never-ending travels in over twenty countries (and counting); and how she identified as a writer and a product of a middle-class family from the Eastern Cape. It also offers telling lessons about race relations in the countries where she lived.

Noni’s extended absence from South Africa, from 1933 to 2002, has made her a lesser-known foundational writer here. Being a woman adds to this: societies such as ours do not give women the same regard they do men. When she did return home, it was always for brief periods, during which she could not resettle. But thanks to her writing, her legacy will live into eternity; and her wish, held for many years, that she would die in South Africa, was granted.

When Noni returned for good, a Zimbabwean writer, Virginia Phiri, who helped facilitate her return, accompanied her from Harare, via Johannesburg, to the Lynette Elliott Frail Care Centre in East London, where Lynette her and husband welcomed them. Noni became the first occupant of the centre and lived there until her death in 2008. During this period she reconnected with family members and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the South African Literary Awards (2005).

Unfinished and as yet unpublished writings by Noni include her further memoirs and the biography of her father, DDT Jabavu. She was undertaking research toward this book when she visited South Africa in 1976–1977, travelling extensively as her research demanded. There is a high probability that her earlier memoirs will be reissued by South African publishers; then, hopefully, as she wrote in the Preface of the first South African edition of The Ochre People in 1982—

Now that this book which I wrote nearly twenty years ago is being reissued, I confess I am pinning the hope on it that it may put me in touch with a whole new generation of my fellow South Africans; that it may introduce us to each other across the celebrated ‘gap’! For although I am not a hundred years old, or even three score ten yet, I seem in my life-time to have missed out on three contemporaneous generations of my compatriots—that of my own age-mates, and those of their children and grandchildren. I have been prevented from being at home with them physically, except now and then for short periods, few and far between. My loss and sorrow have been very great.

Published Biographical Fragments, Book Chapters and Related Writings

2007

Xaba M. Noni Jabavu: Product of powerful women in South African Labour Bulletin vol. 30 no.5 December/January 2007 Parkmore; ed. Kally Forrest (p69–71).

Xaba M. Journeying with Noni Jabavu (a reflexive essay) in WiSER in Brief Vol. 5 no. 1 May 2007; (22–23).

2008

Xaba M. The Pioneer, Noni Jabavu in The face of the spirit: Illuminating a century of essays by South African women, published by Beulah Thumbadoo and Associates on behalf of the Department of Arts and Culture, Pretoria; compiler Beulah Thumbadoo (p53–54).

2009

Xaba M. Noni Jabavu Pioneer, Émigré and Writer (a tribute) in Baobab South African Journal of New Writing; ed. Sandile Ngidi Vol. 3 (p38–45).

Xaba M. Noni Jabavu: A peripatetic writer ahead of her times in Tydskrif vir Afrika-letterkunde Vol. 46 no. 1. Pretoria (p217–219).

2011

Xaba M. We need money and time: Putting women on the biography agenda in A Megaphone: Some enactments, Some Numbers, and Some Essays about the Continued Usefulness of Crotchless-pants-and-a-machine-gun Feminism, eds. Juliana Spahr And Stephanie young, Chainlinks, Oakland and Philadelphia, 2011 (p191–194 & 257)

See also:

Masola, Athambile. ‘Reading Noni Jabavu in 2017’, Mail & Guardian 11 August 2017: ‘Without poet Makhosazana Xaba’s work on Jabavu’s biography, we would not have been able to see how Jabavu negotiated borders, because her life story spans very different homes—ekhaya nasemzini: home and the home of marriage—as well as the many other countries she visited during her lifetime: Britain, Jamaica, Italy, Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe.’

- Makhosazana Xaba is a Patron. She is the author, most recently, of the collection of poems The Alkalinity of Bottled Water (Botsotso, 2019) and the editor of Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000—2018 (UKZN Press, 2019). She is currently a Research Associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER), working towards a biography of Noni Jabavu.

9 thoughts on “On Noni Jabavu and the return home—Makhosazana Xaba celebrates one of South Africa’s foundational literary centenarians”