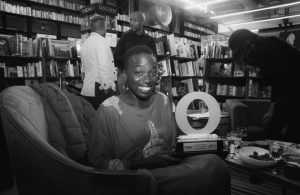

The JRB is proud to present ‘Mothers and Men’, OluTimehin Adegbeye’s Gerald Kraak Prize-winning essay.

The Heart of the Matter

The Gerald Kraak Anthology: African Perspectives on Gender, Social Justice and Sexuality, Vol. III

Jacana Media, 2019

The Gerald Kraak Prize honours African writing and photography that ‘provokes thought on the topics of gender, social justice and sexuality’.

From the statement on the winner from the Jacana Literary Foundation and The Other Foundation, which jointly sponsor the prize, the judges:

were taken by the fierce intensity of ‘Mothers and Men’, a meditation on the bonds between mothers and daughters. The essay explores the fragility of healing with a rare sensitivity and insight. OluTimehin Adegbeye’s voice walks the fine line between heartbreak and redemption, casting new light on questions of rape and secondary victimisation in ways that are new and important. Adegbeye is an urgent and timely voice and both her substantive interests and her prose and befitting of a prize that exists to champion human rights and complicate the framing of what it means to be African today.

This year’s judging panel comprised Sisonke Msimang, Mark Gevisser, Sylvia Tamale and Otosirieze Obi-Young.

Adegbeye’s essay is published in The Heart of the Matter, the third volume of the Gerald Kraak Anthology, published by Jacana Media.

Read the essay:

Mothers and Men

Waking up the day after my mother’s death, I recognised the dazed confusion I was feeling as a throwback: On a humid morning five years prior, I had gone to school in a body that had been recently broken into, and everyone had seemed so … normal. In response, I was filled with a scrambling anger, a deep bewilderment, at the audacity of the world to keep stupidly spinning as if it had not abruptly ended. As if life had not turned itself shamelessly inside out, in order to teach me that dying can happen even to people that are loved beyond reason. That long-ago day, my mother’s lap had held all of me in it, including the parts that had been killed. Today, my mother’s lap is gone.

If my memory knew how to cooperate with my heart, I would never have difficulty remembering my mum’s features. But it’s been six years since she died, so her face and voice fade in and out, clear only in dreams. Still, a face is far easier to forget than the feeling of being thoroughly loved, and I remember, clear as day, the way it felt to be in her lap as my English teacher whispered into the still air of our living room that someone had raped me. I folded into her in the too-small armchair, trying to make myself invisible as my mother listened to a stranger talk about her daughter’s violation, their voices sinking lower and lower as if turning the volume down would lighten the weight of what was being said.

Usually, when I tell the story of my mother’s reaction to the news that her sixteen-year-old had been raped, I talk about crying in her lap. I say she cried with me, even though I don’t remember this for sure. I talk about her making me feel something like the possibility of eventually being okay, even though I don’t remember how exactly. I don’t talk about her decision to confirm if there was anything left of my hymen; that after my mother learnt someone had raped me, she scheduled a visit with a doctor to see if the rapist had left anything behind.

We never talked about sex, Mummy and I; never talked about boys or girls or desire or violence. She told me once and only once not to let any uncle touch me under my skirt, but I always wore long skirts; there were vast expanses of skin under them and at the time of this instruction, even I had not found the parts that mattered most. A decade later, lying on my back with my naked legs splayed out on an examination table, my mother would stand and watch as a man tried to force his fingers into me. By then, I had discovered that the parts he was excavating were the parts she had been referring to.

The gynaecologist, an old church leader who I would later find out needlessly cut women open for the extra Caesarean-section money, reassured my mother from between my legs that my defilement had been botched. ‘Good news,’ he declared, as he tried and failed to fit his bunched fingers inside me, stripping me of the opportunity to grieve being pinned down and penetrated by a man who I had secretly, shyly wondered what it might be like to kiss. For the second time that long-ago week, I watched myself from the outside of my still, prone body. A man was inside me, uninvited, because a man had been inside me, uninvited.

My post-rape body could not accommodate more than two of his fingers, so the doctor surmised that what my mother was worried had happened hadn’t happened after all. When it mattered most, there would be enough resistance that neither God nor my husband would have to forgive me anything.

The torn and bloodied skirt that I had squeezed into a corner in my bedroom, the fact that my brain was erasing data because my memories hurt too much, the bruises on my arms and neck, the feeling of being inside a body blown wide open—none of that mattered. It was the third day, and the parts of me that had been killed were pronounced living once more.

My mother’s relief filled the room like cries of hallelujah, leaving me no space to burn or bury my death. I watched my body pull itself upright, get dressed with my mum’s help and walk slowly out, leaning against her solid warmth. No one washes the wounds of the resurrected, so I spent years drifting; a corpse trapped inside my cracks, straight into the mouths of hungry men who knew the smell of rotting flesh. I did not have the words to tell my mother that when the rapist showed me that I was a visitor in my own body, I almost managed not to believe him. I did not have the words to tell her that it was the doctor, with his rummaging fingers, that made me believe him. I did not have the words that mattered and neither did she: We never talked about any of it again.

When my mother died in July 2012, I had been reluctantly housing another human being for six months. A few nights after my siblings broke the news of the baby to her, I stumbled upon her sitting on the steps behind our home, back bent in a broken way I had never seen before, weeping. She was talking to herself, but I heard how easily she found the words to describe the occupation of my womb as entirely her own failure. The sight paralysed me. I wanted to rest my head in her lap and weep with her, to untie both our tongues and unravel the complicated truth together. I wanted to tell her that the doctor had put his lies inside me after that man put his anger inside me, and both had forgotten to take themselves out. The debris they left behind confused the part of me that had accidentally learnt which things under my skirt were mine to defend, mine to protect. It was not entirely her fault. Maybe it was not her fault at all.

This is the truth I would have told her: I discovered the worthlessness of ‘no’ when I was sixteen, and my body spent the next four years trying to remember how to form the word. On the way, in the wake of yet another boy who thrust his insistence into my body; ‘say yes, say yes,’ another living thing found its way into me. A thin stick, wet with urine, shaking in my hand yet somehow tilting the universe. Am I pregnant? My body was constantly being invaded by things I deeply wanted to say no to, all of them painful and premature deaths. But here I was, suddenly incubating life; I, who had been unsure how to go on living, fumbling onto mouths and hands and ugly protuberances to feel alive. Trembling, I called my sister.

‘I’m dead.’

If I know anything about how to hide my crumbling parts, it is because my mother was a good teacher. The news shattered her, but besides the night when I saw a thing I was not supposed to see on the back stairs of our big house, I never saw her pain over my unplanned pregnancy. She never let me know what it cost her to sink from being an Exemplary Wife, the First Woman to do this or that in her profession, a Deaconess and almost-Pastor, to the Mother of the Girl Who Went and Got Herself Pregnant. But I know it cost her. I saw it in the eyes of the people who cast sidelong glances over her gleaming casket at my half-heartedly concealed stomach, felt it in the too-tight hugs reserved especially for me at her graveside, heard it in the knowing whispers I was too stunned by grief to bother to decipher. And I saw it in her journal, the one in which she told her God what she never told her children: that she was ready—eager even—to die. 28 March 2012. A prayer I could not read through the sudden tears. I don’t know what to do about all this, Lord. Give me strength.

The night my siblings told my mother that I was pregnant, I was hiding behind the door, having snuck back home from my out-of-state university without her knowledge. She watched her husband wordlessly walk out of the living room, then turned towards my brother, the blooming panic in her eyes slowly settling into something heavier. ‘I thought you were going to tell me something had happened, that maybe she had died … At least my baby has not died.’ When she sighed, it was the sound of the heaviness in her eyes spreading into her whole body. My siblings slipped out, their solidarity having served its purpose, and I revealed myself. Silently, my mother took me into her too bright, under-used study. There, she pulled me close—love and kindness in one hand, surging grief in the other. I thought I would choke on the tumult between us, on all the things we needed to say. We had always had a deep love for each other, but for years, as I rebelled, it had become a quietly difficult love; a vast, vaguely turbulent ocean of it. Neither of us knew how to cross safely to the other side, so we looked each other in the eyes, saying the things that could be said.

‘How did this happen?’ It was a silly question, the only question there was space for between a mother who clung to Jesus for her sanity and a daughter who had forsaken Him for the same reason. The answer that came out of my mouth was meaningless, forgettable; the truth, unutterable.

I don’t know who owns my body. There is violence in their hands, these men, and you did not protect me.

But my baby … there is no protection. The words would never come out of her mouth; my father’s hands around her throat would not let them.

There was a boy in uni who worked my frozen legs gently apart for two years then one night entered me and cried with me because he thought I wanted it even though I said I didn’t. There was a man who danced with my body till it sang then told me to push through the pain when it said stop. There was the one who saw the no, the maybe not, in my eyes, and said yes for me. Before them, there was the man who pinned me down. After him, there was the doctor you asked to pin me down. I got lost somewhere in there, Mummy. And now this baby has found me.

He hurt me, Mummy. But you saw my wounds and you bound my mouth. And you did not help me. Unsaid, the words were on my tongue for my mother, and on her tongue for hers.

Months after that night, just as my body began to shift to make room for all of the living that was happening inside it; just as my mother started to tease me, eyes closed because she was so deeply tired, about how caring for her weakened body was good practice for the one I was about to birth, she died. It was a regular morning, with me doing regular pregnant student things like snacking on day-old boiled corn on my way to write an exam. I was running late and she was still asleep, so I stuck a note to her food tray with some plaster: I love you, Mummy. See you later. That evening, my family told me that my mother had stopped breathing and no one had been able to remind her to start again.

Like the first time my world was upended, I abandoned my body. The screams filling the room were mine, as before, but this time they emerged so completely without my say that I found myself wondering dazedly about their origin. Somehow, I was on the carpeted floor without putting myself there. Somehow, I wailed for my dead mother in the mother tongue she had struggled to teach me in life. Somehow, my mother was no longer alive. Until that moment, it had not once occurred to me that this was a thing that was possible. She’d been very sick, but she was getting better. Right? Right?!

I asked the question over and over, mindlessly, turning to my sister, my cousin, my aunts, in confusion. She was getting better, wasn’t she?! She was eating again; I had spent hours combing Ibadan for the perfect amala for her. She was always asking me to sing to her. She had even started making loving jokes about my pregnancy, about this baby that she had previously prayed to God to quietly take away; let this cup pass from me, Lord. On the night I hit eleven weeks, she asked me to join in the prayer, so I spread a towel on my bed and slept on it in anticipation of a miscarriage. The next morning I put the immaculate towel away and wondered about a God who could only be relied on to kill His own Child.

Here is a lesson learnt hard: the apocalypse is always a private event. Mary and Mary were forced to watch the man they loved scream for a Father who had abandoned Him; the earth shook and the sky split open, but even that was not the End of The World; only the end of theirs. On the night my mother died, I raged at the same Father on her behalf and mine, because in those final months it had finally started to matter more to her that I was alive, that I was whole, than that I was pure. Everyone said Judas was the traitor, but I had been resurrected before and I knew in whose name that betrayal was carried out. That night, I called my mother’s God a liar at the top of my voice, screaming the word over and over at the heavens. No one tried to correct me.

Eventually, the world and my mind settled into a dull sort of silence; I knew I was awake, but everything felt leaden, dense, completely devoid of meaning. I felt myself walk to the morgue, vaguely registering the contact of my feet with the ground, the touch of the cold air on my skin. I was distantly conscious of an incomprehensible slowness, of voices entering my ears as though uninterested in delivering any real message, of the compression of time and reason into a moment that had passed yet continued interminably.

My mother’s emptied-out body was presented to me. There it was, the flesh she had inhabited, where I had begun, which I had clung to for breath and healing and for want of a safer place to be even in the rare but catastrophic moments when she herself was not safe. Her back was straight, eyes dry and fixed shut. The body offered me neither hand to hold nor lap to lay my head or my heartbreak in. My own body felt tight, too full of new skeins of a gouging sorrow. My lungs heaved desperately, futilely; the air in the mortuary was stale, designed for the dead. I stepped outside and caught my breath, as well as the tail end of a morbid joke my brother was making. When I started crying again it was because I was laughing; laughing that my life felt like a raw, seeping wound; laughing at the madness that was my continued existence in a world that was a turtle struggling to get off its back, a world where a daughter was growing inside me and my mother was gone.

One of my mom’s gathered friends stared intently at my stomach, her gaze full of the recently gleaned knowledge of my pregnancy, and I felt a premonition of my sudden exposure to the things my mother had protected me from. I remembered her face after I revealed I had no desire to redeem myself in society’s eyes by marrying the man I’d made the baby with. She had looked slightly confused, then almost impressed, squinting at me as if she were seeing me for the first time. She had taken my hand, her eyes still holding mine. ‘If that’s what you want—whatever you decide—I will support you.’ The pain was a living thing feasting on my bones. The tears would not stop.

Not long after the funeral, my sister suddenly paused as we laughingly swapped small, safe memories; the kind that filled our chests but held the tears in our throats at bay. ‘You know,’ she resumed with intention, ‘Mummy kept asking me for you before she died. ‘Bá mi pe Tìmẹ́hìn. Níbo l’ó wà? Tìmẹ́hìn dà? Níbo l’ọmọ mi wà?” She repeated the words the way my mother must have said them; in Yoruba, with growing desperation. I knew what she meant: Mummy loved you so much. Do you know how much she loved you? I swallowed the recollection whole, struggling to keep playing by the rules my sister had just broken. Failing, I held my fluttering belly, and wept.

- OluTimehin Adegbeye is a Nigerian writer, editor and activist whose work focuses on rights-based issues in the areas of gender, sexualities and urbanisation. Follow her on Twitter.

Very good write-up. I absolutely appreciate this site.

Thanks!

Such beautifully sad writing.

I’m in tears because I totally understand this. I have lived it… Probably still do live it.

This was such a heart wrenching read, the emotions so raw, and this so beautifully written