Despite a strong heritage stretching back more than a century, South African fiction remains largely unfamiliar—apart from a handful of works—to global publishers and reading audiences. The presence of South African writing in international spaces still comes across as surprising or novel, with our literatures often described as ‘emerging’ or some variation of this. I find this curious, given that South Africa is one of the few African countries with a self-sustaining publishing infrastructure and a domestic industry that produces dozens of local fiction and non-fiction books each year. Despite this, our work by and large is not widely available globally: there’s hardly any South African cross-pollination within the African literary diaspora. Is our literature perceived as insular? Is SA lit, in fact, an insular space?

I spoke to Michael Barron, an editor at Melville House Publishing, about these questions and more. Melville House is an independent publisher founded in 2001 and located in Brooklyn, New York, USA. It has developed a world-wide reputation for its rediscovery of forgotten international writers, and also takes pride in the many fiction writers it has debuted. Barron was formerly the Books and Digest Editor for The Culture Trip, where his beat encompassed global literature in all its hemispheres.

Mbali Sikakana for The JRB: What, in your opinion, is loaded and assumed within the phrase ‘emerging South African fiction’?

Michael Barron: ‘Emerging’ is an ambiguous, if not dubious word. Especially for an editor such as myself outside of a so-called emerging literary culture, I’m not sure what such literature is meant to be emerging from or into. Does emerging mean new, as in contemporary? Or does it mean young, as in writers who have only begun to publish? Or does it mean writers who are already known in South Africa who are only now making movements beyond its shores?

There is an element, too, of backwardness to ‘emerging’, as if to say South African literature is finally coming out of a dark age. Of course it isn’t, but using it as a pitch to foreign English-language editors, ‘this is one South Africa’s great emerging writers’, immediately puts such a writer at a disadvantage, coming off as not fully-formed or ready for American publication. At least for me, I would want to consider emergent South African writers as people who are already turning heads there, winning awards and accolades, regardless of age, but also as writers who have the best chance of making splashes abroad.

The JRB: How much of our so-called emerging fiction do you come across organically in the US?

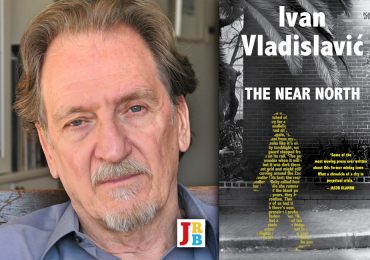

Michael Barron: Not as much as I would like. I am seldom pitched South African writers. I don’t much hear from South African publishers or agents. Many South African writers who are published in the States do so through universities who don’t always have great distribution or publicity. The best place to find South African literature being published in the United States is McNally Jackson, a local [New York] bookstore that has a dedicated African literature section. The contemporary South African writers I do know about I know through word of mouth from other South African writers or other writers interested in South African literature. I know about Masande Ntshanga because Ivan Vladislavić mentioned his name at an event here in New York as being a South African writer he was excited about. Then I noticed he was a finalist for the Caine Prize. Then I noticed he was writing for places like Vice and Rolling Stone and was active on Twitter, which is how I was able to get in touch with him. Then I noticed an American publisher, Two Dollar Radio, had picked up his debut, The Reactive. I believe he has another novel coming out soon with them.

That’s checking all the boxes, but there are other ways I have come to know South African authors. I know about Imraan Coovadia because he attended university with editors who formed the great culture and political journal n+1, a venue to which Coovadia has contributed sharp essays. I reached out to him after reading his great and sprawling novel Tales of the Metric System, which had been recommended to me by one of n+1’s editors. Imraan and I met while I was in Cape Town and had an enlightening conversation on the state of contemporary South African literature.

I know about CA Davids because Ben Williams, the publisher of The Johannesburg Review of Books, told me I should be aware of her work. She happened to be in New York at the time so we met for coffee. Now she’s on my permanent radar and though I am not publishing an American edition of The Blacks of Cape Town I do anticipate getting a chance to see the manuscript for her forthcoming novel.

The JRB, I will add, is also a prime resource for me in discovering or following South African writers.

The JRB: What is the reception and appetite for South African fiction in the US?

Michael Barron: African literature is hot right now, especially English-language literature. It’s not uncommon to walk into a bookstore and see featured on a new and noteworthy fiction shelf, a handful of novels by African writers. It’s not uncommon either to see featured in a publication such as the New York Times Book Review works by African writers, particularly African women writers. So the appetite is there, but it doesn’t seem specific to one country (though for a moment such attentions seemed focused on Nigerian writers). Instead, it seems that many of the African writers making themselves known here are ones that have been educated here or have spent time here or have emigrated to the United States, and thus have the means to get known here exponentially faster. I don’t think living here is a requirement to get known or published here, but it is an advantage.

The JRB: It seems rare for South African literature to be casually identified as representing ‘African fiction’ globally, in the way that West African fiction is, for example. Is South Africa an interesting contemporary literary destination, generally, and why?

Michael Barron: To me it is, but this goes back to that emerging versus emergent question. South Africa has a long and celebrated literary heritage, with two Nobel literary laureates no less, but it does seem like, after apartheid, international interest in South African literature declined. Yet it wasn’t as though South Africans dusted their hands and called it a day. Writers like Ivan Vladislavić and the late K Sello Duiker have helped create a post-apartheid literature that continued that heritage. And the Universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand both have writing programmes, which is a sign that South Africa’s literary culture is not only alive, but thriving. Having visited bookstores in both Cape Town and Johannesburg, it’s obvious that this is so. It was thrilling to go into a South African bookstore and be made aware of an entire literature that I had little idea existed, yet it was humbling too to realise just how ignorant of this ongoing heritage and culture I had been.

The JRB: When applying efforts to investigate contemporary South African fiction, what kind of books, themes, and authors do you find regularly and easily?

Michael Barron: Nothing is regular or easy when you have to investigate it yourself, unfortunately! My tastes tend toward literary fiction and narrative non-fiction, especially on contemporary issues that might resonate with readers here, so I depend on places like The JRB or Words Without Borders to keep me informed on literary writers I should be paying attention to. I try and follow shortlistees and winners of various African literary prizes such as The Caine or the Etisalat (horrifically now named the 9mobile Prize for Literature). I root through the Kwela Books catalogue from time to time, too. More South Africans are writing for American publications, and so if I see a byline in a magazine by a South African writer, I’ll do a bit of research on them.

The JRB: Do you personally enjoy the ‘emerging’ South African literatures that you come across?

Michael Barron: I am always curious about South African literature, emerging or emergent, but I have to confess that it can be hit or miss. Sometimes I’ll be very interested in what I come across or am made aware of, but just as often I’ll discover writers who seem talented but who also come off as unpolished, if not immature. I don’t necessarily think they are bad writers, but rather, I’ll find myself wishing that their writing had been given a much more rigorous edit. Poor editing or unclean writing are big factors in what would stop me from acquiring someone’s work, even if it has already been published by a foreign publisher.

All of which isn’t to say that I don’t see potential in a lot of what I come across, looking at South African writers. I often do, and try to follow up with writers whose work catches my eye. But it does take a good editor, or even a good agent, to help a writer develop their prose from flawed to flawless, to help make their insights crystalline, to help turn cursory, clumsy, or unnecessary passages into ones that you’d want to quote from or underline. A good way to learn this is, of course, writing for newspapers or magazines where being edited is par for the course. You will not only get published, but you will be made to think about your writing in ways that will come in handy for something like a novel.

In this way, and in my capacity as an editor for an American publisher that is distributed globally, I see myself as a South African writer’s next step. I don’t want to be the first book editor a South African writer has ever worked with, but rather, ideally, a writer should have already been groomed to a degree by South African editors before I see them. There should be a degree of curation, you know, so that what I am considering is really among the best writing in South Africa today. And since there are so many South African writers, it’s up to an editor, or a prize committee, really, to choose who the crème de la crème are at any given time. South Africa is a literary country and it should go without saying that from it might emerge (yet another variant of that loaded word) writers who have talents that could be appreciated, even celebrated, abroad. Writers who not only write on topics that have universal concern, but are able to do so with singular style and voice. Finding those writers, from wherever in the world they come, is what I enjoy most about my job.

The JRB: Young South African authors in particular are waking up to the availability of new audiences abroad and are exposed to contemporaries pursuing these new audiences through indie presses, new and established. What would be your advice to such authors, especially those without agents for representation?

Michael Barron: Many South African writers have the great advantage of writing in English, meaning any English language publication is fair game to pitch to. If you want your work to get noticed in America, or the UK even, pitch to American and UK literary journals and magazines. You don’t need an agent to do that, and many editors at those places probably wouldn’t mind a pitch from South African writers. Here’s a list: The New York Review of Books, The London Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times Book Review, The Paris Review, n+1, The Point, The New Republic, Still, The Nation, Jezebel, The Cut, Jacobin, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Granta, The White Review, Lit Hub, Vice, Guernica, GQ, Rolling Stone, Harper’s, The New Yorker, and so on.

That’s a lot, but they all have their interests. Start by pitching online pieces to these places as online is the easiest to break into. Americans in particular love writers who are as fluent in journalism as they are in fiction and because of that it’s much easier to get a narrative piece of reportage online at a place such as The New Yorker than it is to get a short story placed in its print pages. You can always work toward that goal. But even an online piece might go viral or at least get noticed by an agent.

An active writer is a writer I’d want to publish. No one should sit around twiddling their thumbs waiting to be contacted, nor should people assume that finding a publisher for your book is the only step. You have to want an audience, so it’s up to you in large part to build one and get people hyped for your work. Have an active social media presence. Get into conversation with other writers on Twitter or even email. Pitch pieces to the places mentioned above. Don’t be afraid to put yourself out there. The more heads you turn, the bigger those heads will be.

The JRB: How can South African writers ‘reach you’ as an editor at this time?

Michael Barron: Well, I’d rather not get inundated with cold emails so I’m afraid I can’t just post mine. The best way to reach me otherwise would be through an editor, agent, or even a writer that might know me. I always have an ear for recommendations. Alternatively, you could go to the Melville House website and look up our general submission channels. If you email and put ATTN: Michael Barron, it’ll get to me. I can’t guarantee that I’ll get back to you, I just get too many pitches to respond to them all, but I will try. Otherwise, if you are active and talented, I will be on the lookout for you.

- Mbali Sikakana is a regular contributor to The JRB. She holds a Masters in Publishing Studies from Wits University, and has a passion for the entire value chain of writing and books.

- Michael Barron, currently at Melville House Publishing, is an editor and writer who was formerly Books and Digest Editor for The Culture Trip, and who has appeared in numerous publications. He is currently writing a book on the cultural history of banishment.

Hugely informative interview. Thank you Mbali and Michael.

Great questions, amazing answers. Brilliant stuff. If one reads one article this year, this be it.

Speaking as an Australian blogger writing reviews of LitFiction from around the world, (see South Africa in the categories on my blog) I second the suggestion that the JRB and Words without Borders are excellent sources for discovering what’s new. Through them I discovered Mohale Mashigo, Fiona Melrose, Nomavenda Mathiane, and Fred Khumalo.

With the good fortune to grow up in a bookish family, I feel that I have always known of Gordimer, Lessing, Coetzee, Brink and Slovo… and through various prizes I discovered Damon Galgut, Lewis de Soto and Barbara Trapido.

But I discovered Zakes Mda, and Njabulo Ndebele, Alex La Guma via the (now defunct) Heinemann African Writers Series and so I think there is a place for a series like that, harvesting and marketing the best of writing from around the continent for readers around the world.

I would also very much like to follow a South African blogger who reviews (in a serious way) SA Lit (similar to the way I focus on Australian Lit), but although I follow two bloggers from the continent both are from Ghana, I don’t know of any others. I know from my own following and blog stats that blog reviews are a powerful way to expose a minority literature (i.e. anything not from the US or UK) to an international audience. Perhaps the JRB could include a blogroll of recommended Litbloggers of SA Lit?

Yea I also don’t enjoy south African authors style of writing, I think these publishing institutions should invest heavily on editors/or editing. Surprisingly the only book I enjoyed by a SA’n was Trevor Noah’s book (wonder if his was edited by a SA’N or not).