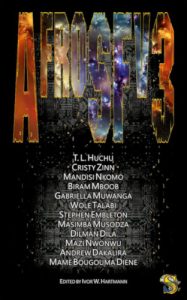

The JRB presents ‘Njuzu’, a new short story by TL Huchu, excerpted from AfroSFv3.

AfroSFv3

AfroSFv3

Edited by Ivor W Hartmann

Storytime, 2018

~~~

Njuzu

Water looks the same everywhere. It’s only the background, lighting, and impurities, that differ. I peer at the silver-grey surface of Bimha’s pond, calm and still, undisturbed by wind. It’s deep and the bottom is a black abyss. Midday here is like dawn on Earth in the middle of the Kalahari. Light shines through the transparent panelling of the pressurised geodesic dome that prevents the water boiling straight into vapour.

‘This is where it happened,’ VaMutasa says to me on the crackling open channel.

We can’t take off our helmets because the atmosphere within the dome is not fit to breathe. I take a step closer.

‘Careful,’ Tarisai whispers.

A trail of small footprints runs beside me. We followed it here, but where we stop, it carries on, bravely, foolishly.

‘This is where it happened,’ VaMutasa says once more, as if to convince himself.

The icy brown soil under my boots feels hard. Each movement I make is slow and considered. A white plume of steam rises from the outlet pipes a kilometre or two away, the far end of the pond. Thirty million gallons of water cycle in and out of the Nharira Nuclear Fusion Plant nearby. Superheated steam is deposited into the ground, liquified and the cold water is cycled back to the plant via insulated pipes.

I close my eyes and take deep breaths, fighting the sickness threatening to void my stomach. My chest feels tight, tied with an iron band, and I reach to remove my helmet so I can breathe. My husband grabs my arms:

‘Remember where you are,’ Tarisai says. ‘I told you this would do no good.’

The tone of her voice is reproachful and she’s angry, a dam waiting to burst. But on the open channel, with everyone listening in, we save the argument for later, piled up with the rest of the little tears and scraps every marriage sweeps under the bulging carpet.

I must be polite; the muroora, daughter-in-law, is not just married to one person. The bond of matrimony ties her to everyone in the clan, both the living and the dead.

‘It’s important, whatever you do, you mustn’t cry,’ VaMutasa says. ‘The njuzu won’t let him go otherwise.’

‘My son’s just drowned and you’re talking about mythical creatures?’ I snarl but hold my tears all the same. Even though I know it’s superstition, something inside checks me, because, with the chips where they lie, all I can do is hedge.

‘One of the technicians, Chisumbanje, fell in the water twenty years ago. For three days, we couldn’t find him. Then, when he came back, he was a powerful n’anga without equal in the Belt. He saw her, the njuzu. She’s in there,’ a woman’s voice says, but I don’t recognise it.

‘Whatever you do, you must-not-cry,’ VaMutasa says, this time in a firm voice. ‘We’ll prepare the rites.’

He is my father-in-law, Tarisai’s father, the head of the Mutasa clan. Their fortune is made from farming the desert and selling water—hydrogen and oxygen—to wayfarers passing through to worlds beyond.

#

We’ve only been here a week and it’s hard to get used to the eighteen-hour days. Dusk, when it comes, is swift, a minute or so long, the faltering of a fluorescent bulb marking the turn from light to darkness.

I stay in our Hurungwe Utility Terra Shelter, lying in bed; my molars ache, I feel they might shatter into sharp shards of glass. From outside comes the sound of silence so loud it presses on every ounce of my being. Tarisai isn’t here to hold me. She’s out with the men in the search party who now radio in as the recovery team. She’s my husband, so she must. This place is tough and unforgiving. We should never have come back.

I feel helpless. Hopeless.

Don’t cry.

#

I wake sometime before dawn. My husband’s arm lies across my chest. It’s heavy and strong, and she smells of sweat from the search. She’s a snorer, but tonight she is quiet, a slight frown on her face.

Gently, I remove her arm.

The carbon fibre walls of the HUTS we’re in are decorated with Tonga artwork from the tourist market in Mosi-oa-Tunya—reed ruseros and baskets with intricate designs woven by married women past childbearing age. There’s an abstract sculpture made of polished Cerean rock. A red Basotho blanket hangs on the wall opposite.

I creep out of bed, wear my suit and go into the airlock, checking my oxygen tanks are full up. With the CO2 decarboniser, I have up to fifteen hours’ worth of air. My son Anesu with his small lungs would have had a little more.

The airlock door creaks and I hope it doesn’t wake Tarisai as I walk out and shut it behind me.

Fierce lamps, high up on poles like stadium lights, illuminate the compound. The yard has wide open spaces in which the HUTS are erected. They are domed, like Zulu huts with small round port windows. There’re fifteen of them here (one medical and two for emergencies), a few equipment stores, and in the far-off distance is the large mess where we take our meals. Beyond the compound, the valley is littered with hundreds of settlements, everyone trying to earn their fortune in the Wild Belt.

I walk, adjusting my body to the microgravity, so I sort of waddle and shuffle, bouncing from side to side. The trick is to lunge forward, so the momentum carries you horizontal to the ground. The few times I go too high up, my auto-downward thrusters kick in to push me back down, releasing a thin jet of gas.

The ground is rocky and bumpy. Footprints from years ago remain pristine in the wind free space.

I walk past the Mutasas’ ancestral graves. Mounds of dirt like mole homes, topped with simple headstones, where the dead lie in frozen ground.

Beyond that, a short distance away, are their farms. Massive greenhouses with controlled air, temperature, and water, turn the fertile soil of this desert world into an oasis. They grow lettuce, onions, tomatoes, cucumbers, wheat, maize, anything they wish at all, because the once barren soil, rich in carbon and organic compounds, is hungry for life. Ceres, named after the goddess of agriculture, is generous in her bounty, feeding miners across the Belt and colonists on Mars and beyond.

I search for my son’s small bootprints until I find them, heading out to the waterhole. Sometimes they’re obliterated by his companions, other times his small print sits square inside a larger print. The children come here to play games on the water. In the low gravity they can run on it, just like basilisk lizards on Earth.

Eight years ago, I sang the Song of Life and knitted him into being with my two hands. After I missed my period, my mother came to me, bearing my trousseau of linen and jewellery. We sat face to face on my marriage bed with our legs crossed and sang:

Ndinowumba musoro wako

Ndinowumba maziso ako

Ndinowumba mhino yako

Ndinowumba chipfuva chako

Ndinowumba tsoka dzako

Ndinowumba zvidya zvako

Ndinowumba dumbu rako

Ndinowumba kamboro kako

Ndinowumba rurimi rwako

Ndinowumba twugunwe twako

. . .

For three hours we sang him into being. Each line starting, ‘I create’, followed by the part I willed into being. My hands, index finger on thumb as though holding knitting needles, dancing around my belly as I knitted every atom of Anesu into existence.

The Song of Life was important, every part of his body had to be sung, willed into existence, or he’d be deformed. I heard the response to the Song in his voice, every time he spoke with me. I heard it in his laughter at play and the tears I wiped away when he was sick.

Yet, as I stood on the shores of Bimha’s pond, the sacred duet had been stolen from me. In its place, I only heard silence and grief.

#

Dawn, when she comes, is just a minute long, a step from a dark room into light. Long shadows embrace my legs. The tangerine in the black sky is supposed to be the sun.

‘Where were you?’ Tarisai says. She’s waiting for me at the edge of the compound. ‘Everyone’s looking for you.’

I walk up to her and embrace her. In the bulky suit, I can’t feel her warmth. I feel nothing.

A slow rhythmic drumming, pangu, pangu, pangu, comes from the mess as I strip out of my suit. The air here is too crisp, like something is missing, dust, pollen, the scents of earth.

Hands clap, bu, bu, bu, to the beat of the drum.

Women ululate.

The chairs and tables in the mess have been unbolted from the floor and stacked up in one corner. Hard-faced men and women sit on the floor, separated from one another. Tarisai joins the men. Her anatomy is female, but she hosts the spirit of a man—an ancestor who claims her body for his vessel—and so she is man.

I sit and fold my legs to one side.

Don’t cry.

A hologram at the front projects a life-like nyati, the buffalo, their clan’s totem. A noble and prestigious line. I’m samaita, the zebra, not the bottom of the totem pole, but a little more humble. Anesu, like his father, is—dare I say was—a buffalo too, for the line passes from father to child. The mother is as good as a stranger, her blood does not count.

Chisumbanje is at the front, bare chested, his loins covered by the skin from a black and white bull. Hoshos tied to his ankles rattle when he moves. His head is crowned with a feathered headband as he rocks back and forth to the beat of the drums.

It’s hot in the mess.

Christine places her hand around me and I lay my head on her shoulder. We greet Chisumbanje by his totem name; he is the meat-eating herbivore who stalks silent in the savannah grass, death incarnate, the uncrossable chasm.

He takes a pinch of snuff, inhales deeply and sneezes several times. We clap and chant: ‘Svikai zvakanaka, vasekuru.’

In the corner of my eye, I see Tarisai clench her fists and mutter some words. She is resisting. Her spirit is trying to visit, to gain entrance, but this is not his ceremony, he must wait in the spirit world, stand guard against the evil that would do us harm. Only Chisumbanje will be visited today.

Christine takes me to the back of the room. We carry calabashes on our heads. On Earth, I lack the grace and skill, but here, in the low gravity, my calabash stays on the top of my head, until I place it down by Chisumbanje’s feet. We kneel, clap our hands, stand, and retreat to the women’s side.

The drummer stops. He too is dressed in animal skins and he picks up one calabash in both hands, squats and offers it to Chisumbanje. Chisumbanje shakes his head and rejects it. The drummer pours a drop on the floor to the spirits and offers the beer a second time. Now Chisumbanje accepts with a nod. As their hands meet, the giver and the taker, we clap and the men whistle.

The blessed beer now passes from Chisumbanje back to the drummer, the receiver has become the giver. And the drummer passes it to the men. Twenty thirsty throats take in a sip each. There are one or two miners with us from the next settlement. Gold prices have plunged. There’s too much of it coming from the asteroids, flooding the market. Soon they’ll pack their tools and move to mine another commodity, until it crashes, too.

The ancestor who visits Chisumbanje tells us certain things: Anesu is alive and well in the company of the njuzu. We must not cry. If we do, she’ll be angry and kill him. We must offer a sacrifice to appease her. If we do this correctly, Anesu will return a great healer and seer, a n’anga. She’ll give him gifts without compare from the spirit world.

There are no cattle on Ceres, but we have plenty of rabbits and chicken for meat.

The sacrifice will be a black male rabbit.

#

My teeth ache so bad as I lie naked in bed at night. Any light movement I make jabs a nerve.

The view outside my port window is a purple-green sky, a kind of grotesque aurora showing the frontline of the battle between solar-cosmic radiation and the artificial magnetosphere that stands as the only thing preventing us from being slowly microwaved to death.

I hate this annual pilgrimage.

I want to go back to Earth.

When chirimo, the planting season, comes, we leave our cushy office jobs, pack our bags and go kumusha to help with the farming. We all have two homes, our true home being kumusha where our ancestors are buried. Mine is on Earth, in Manhenga: Tarisai belongs here on this desert world, which she abandoned to be with me.

Yet each time we visit, I hate it more and more, though I try not to let on.

I know it’s the magnetosphere that causes my toothache. The doctors say that’s impossible, but it never happens when I’m on Earth. I refuse to take painkillers. I want to suffer like my son did, alone and scared in the dark.

Don’t cry.

A star moves swiftly across the sky, one of the three satellites orbiting Ceres.

Tarisai comes into the room. Her hard, sculpted body moves slowly, solid pecs showing under the white vest she wears.

‘You left early,’ she says without reproach.

‘That voodoo isn’t going to bring my son back,’ I reply. ‘Do you honestly think some mythical creature took him?’

‘He was with his cousins. They’re experienced Ceresmen. They walk over that pond practically every day, mudiwa. It’s virtually impossible for anyone to drown here. The gravity is far too weak, you couldn’t break the surface tension of the water to go under. But somehow Anesu did. His thrusters must have malfunctioned, pushing him down under the water. We’re trying to figure it out. They were walking in a group, he was a little behind. They got to the far bank and he was gone. For some reason, his transponder isn’t working either.’

‘They were supposed to look after him. He’s an Earth-child.’

‘They did their—’

‘I want my son back!’ I scream at her.

‘We’re doing the best we can. There’ve been search parties.’ She sighs and lowers her voice. ‘You’re not the only one who’s hurting, you know? He was my son too.’

‘You never wanted him in the first place.’

‘Oh, so now we get to it. Are you really going to fling stuff I said in uni back in my face?’

‘You wanted to be free, to explore the solar system, Venus, Europa, Titan, to Pluto and beyond. How many times did you change his nappies? You’d rather have been anywhere else.’

‘But I stayed, because I love you.’

Before I can say the next spiteful thought formed in my mind, she’s on top of me, pinning me down, a rough finger in my dry vagina. We claw, bite, fight like animals as we make desperate love. And when it’s over, we fall back down, sweaty and exhausted, and turn away from one another.

#

In my dream, I sink into black water, thick like oil. The silver moon of Earth shines on my face. I wonder why of all moons, ours has no name, as if it is enough to say what it is. Maybe I should give it a name, call it something kind and gentle.

I sink down, leagues and leagues, down a never-ending abyss.

Until I meet her, at the bottom of the dark.

I never truly knew what a njuzu was. For some, she’s a mermaid, half woman half fish. For others a water sprite, spritely and nimble. Since I lost my son, I’ve thought of her as a spiteful siren, the disastrous enchantress, ensnarer of sailors and young boys. But the reality is she’s neither of these: she simply is what she is.

She sits tall on her throne, Neptune’s daughter. The most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen. Her flawless skin is black like polished obsidian. Tiny bubbles form against it. Her wise eyes sparkle like pearls. Her hair is green and wild like reeds in the river Tsanga.

Anesu is still, wearing a copper necklace on his bare torso. At their feet lie herbs, divining bones, a kudu horn and earthenware utensils.

The njuzu half smiles at me.

‘Give me my son back, you bitch!’ I shout, and the water enters my mouth, into my lungs. I cough and gag, drowning. My chest is full of molten lead as I struggle, arms flailing, trying to reach the distant, moonlit surface where Tarisai’s face looks down at me.

‘Wake up, you’re having a bad dream,’ she says.

#

The stars in the Milky Way lighting my path number less than the kisses I planted on Anesu’s head and brow and lips and feet and every square inch of my baby’s body.

Fury and fear draw me back to Bhima’s pond like an iron filing to a magnet.

The sun is yet to rise in the dark green sky.

The still surface of water meets my boot and I walk on it. It is soft and gently displaces creating ripples that fan out in front of me. I try to peer under the dark surface, in the depths where my Anesu must be. I sing the Song of Life as I walk upon it, each step, recreating him, my gloved hands knitting him piece by piece.

Tarisai appears on the shore. She’s a tiny figure in her bright red suit. The light on her helmet points at me. I know she hurts, too, but there’s a magnitude of pain only a mother can feel. So, I give her a wave. She stays where she is, my silent guardian.

When I reach the middle of the pond, I let go of the lie of hope and slowly let it fall into the water. I know my son is lost forever.

His spirit wanders the cruel, cold depths of Ceres.

I cry. Large hot tears fill my helmet until I’m blind and I can see his face looking at me again.

- TL Huchu is a Zimbabwean author, best known for his novels The Hairdresser of Harare (2010) and The Maestro, The Magistrate & The Mathematician (2014). He was shortlisted for the 2014 Caine Prize and won the 2017 Nommo Award for Best Short Story. His work has appeared in Interzone, The Apex Book of World SF 5, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, The Year’s Best Crime and Mystery Stories 2016, AfroSFv1, and elsewhere. He enjoys working across genres, from crime to sci-fi to literary fiction. Currently, he is working on new fantasy novel. Follow him on Twitter.

About the book

Space, the astronomical wilderness that has enthralled our minds since we first looked up in wonder. We are ineffably drawn to it, and equally terrified by it. We have created endless mythologies, sciences, and even religions, in the quest to understand it. We know more now than ever before and are taking our first real steps. What will become of Africans out there, will we thrive, how will space change us, how will we change it?

AfroSFv3 is going out there, into the great expanse, and with twelve African visions of the future we invite you to sit back, strap in, and enjoy the ride.

AfroSFv3 received four 2018 British Science Fiction Association nominations for: Cristy Zinn, ‘The Girl Who Stared at Mars’; Biram Mboob ‘The Luminal Frontier’; Dilman Dila ‘Safari Nyota: A Prologue’; and Stephen Embleton ‘Journal of a DNA Pirate’.

‘The third in this pioneering series with an honour roll of some of African writing’s biggest names contributing. Unmissable.

—Geoff Ryman, author, awarded the Nebula, two-time Arthur C Clarke, three-time BSFA, two-time Canadian Sunburst, as well as the Campbell, Philip K Dick, and James Tiptree Jr, awards‘The compelling, graceful stories in AfroSFv3 embrace a generous spectrum of places and peoples, eras and objectives. From sophisticated space operas to gritty cyberpunk streets; from day-after-tomorrow beginnings to far-off futures; from familial closeness to alien vastness, these well-wrought tales, infused with all the sharp, bright, enticing flavors of their African origins, show us the commonality of our species across all racial, ethnic and gender lines. Truly, these writers speak the same science fiction tongue as their like-minded cousins from the rest of the planet, with beautiful accents of their native soil.’

—Paul Di Filippo, author of Cosmocopia, The Steampunk Trilogy, and others‘With stories ranging from mundane science fiction to distant space opera passing from postcolonial biopunk and new family ties, the latest book of in the AfroSF series shows that inclusivity and multiculturality is the key to the future. As quality storytelling—rooted in every culture and tradition—doesn’t belong to a single country or language, these stories prove that the future—as evident as it might sound although not always considered so—does happen everywhere. Excellent reading!’

—Francesco Verso, author of Nexhuman and editor of Future Fiction

this should be the most beautiful speculative story I have read in almost two years. And I have read a lot.