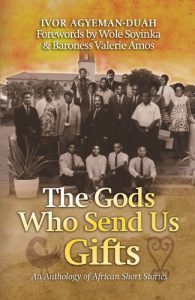

Exclusive to The JRB, read Wame Molefhe’s short story ‘A Woman is her Hands’, excerpted from The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short Stories.

The South African launch of The Gods Who Send Us Gifts will take place at the University of Johannesburg on 16 May, 2018; click here for details.

The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short Stories

The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short Stories

Edited by Ivor Agyeman-Duah

Ayebia Clarke Publishing, 2017

~~~

These words are recited to you before you are allowed to boil water on the primus stove; before you have learnt how to arrange cups and saucers on a tray so you can serve guests tea; when you are still too young to be entrusted with money to buy at the corner shop. Still learning how to sweep the yard—under your mother’s eagle eye, you try your very best to copy the fine, even swirls she leaves in the sand with her grass broom. You have not yet mastered how to balance a bucket of water on your head and walk hands-free. Matches are off limits, so lighting the candles at sunset is a duty strictly for your older sisters.

But you sparkle at shining the special cutlery that the family uses for Sunday lunch. You follow your grandmother’s step by step instructions: a drop of Silvo on a scrap of fabric; vigorously rub the fork or knife or spoon; examine the utensil for smudges by holding it up to sunlight; repeat the process, if necessary; rinse in clean water and dry with a dishcloth. You fold your sheets into tight envelope corners when you make your bed. Like all clean girls do, you wash your panties every day and hang them out to dry in the sun. You know never to walk barefoot in winter because the cold will penetrate your soles, snake past your ankles and calves and thighs. It will reach your womb, damage it, and prevent you from receiving God’s gifts.

When the kgeru-sized lumps sprout in your chest, your grandmother brushes them with a grass broom: up, down, down up, over and over again. Once, twice, she succeeds in flattening them, but her third attempt fails. Your breasts harden, then soften and fill out. On the morning your menses start, she calls you to her room and closes the door behind her. On her face settles an expression you recognise. It is the one she wears after receiving Holy Communion, when she feels most sanctified, replenished. You watch her cross her ankles and study her hands as she irons the creases out of her dress. Wrinkled, as if they have soaked too long in water, blue veins showing through the surface of the speckled brown skin, her nails always clipped straight across the top. She furls her fingers, unfurls them. She rotates her thumbs. Round and round. The indentation above her nose, on her brow, deepens. Finally, after taking a deep breath, she speaks. ‘Run away from boys. They will make you a mother before you are ready… and keep your name out of boys’ mouths and never, ever allow yourself to become a girl of the boys.’

When she is done lecturing, you extract your favourite book from under your pillow. It is the one you chose from the big boxes that the Church in America send to you. You stroll to your favourite spot where you sit in the shade of the huge blue gum trees and disappear into the words of Beth, Jo, Amy and Meg and their world of snowy Christmases. Every time you read Little Women, you promise yourself that one day you will escape your home to live in a place far away where you will become more than your hands.

It is only when you hear mothers’ voices urging children to return to their homes that you realise that daylight has crept away. You run all the way home, but your grandmother is already stationed at the gate when you arrive. She points to the sky and asks: ‘le kaeletsatsi?’ You cannot find the sun that she is demanding from you, because it has dipped out of sight already. The moon has risen. When she spies the book you have clamped against your ribs, she cautions you again that girls who read too much and think too much are inviting trouble.

It is early one summer Saturday morning when the blue, black and white plumaged birds are singing as if to coax the sun from behind the hills. Your mother’s friends and other female relatives have gathered to thrash out the details of your big sister’s wedding. Each suggestion is full-stopped with ‘Ilililili! Ililili!‘ And a light-footed jig.

With a plastic basin held in one hand, a jug of water in the other and a towel slung over your shoulders, you pour water on to the women’s outstretched hands before serving them magwinya you kneaded yourself. Your ears steal snippets of conversations as you pour them tea. They chorus that your sister is a good woman. She has made them proud. She will make a good wife. How can she not raised as she was by a mother whose hands are known the village over? On this day, the line between your mother’s eyes is not visible—not until her sister arrives, stooping slightly in the way people do when they are trying to be inconspicuous. Your grandmother has already opened the meeting by thanking God for the many blessings He has bestowed on them. She presses her lips together at the sight of her daughter.

Unlike the thirty women there, your aunt does not hide her hair under a headscarf; she has coiled her braids into a bun. A few beaded strands slide over her shoulders. She does not wear the uniform that has been specially designed for the day: a German print fabric dress, apron-like with frilly pockets, matching shawl held together with a safety pin. Although your mother has never actually said so, you suspect that Aunt Beauty—who wears her pants so tight they sculpt her buttocks and struts across the village in heels that sink into the sand, who smokes cigarettes and drinks hot stuff at the local spot, was probably a girl of the boys. You suspect that many mouths have spat out Beauty’s name—all over Botswana and beyond. When the final Amens are murmured and the closing, ‘Thanks to God, there is no one like Him’ hymn is sung, she beckons you to her side and pulls out a bottle of nail polish from her handbag. She places it in your palm and curls your fingers over it and touches her index finger to her lips. In that instant, she becomes your favourite aunty. You slip your secret into your apron pocket and press your lips together to keep your smile tucked away.

When a letter arrives from the Ministry of Education, informing you that you have won a scholarship to study in America, for a moment you cannot move. You feel your heartbeat in your head. Excitement tingles in your fingers and the letter falls to the ground. You pick it up and read it again.

‘I’m going to America,’ you scream. ‘I’m going to America.’ You believe America is everything.

The night before you leave your grandmother calls you to her side. Her words are a warning, an amber robot: ‘Do not be fast. Always listen to your teachers. Do not forget the good manners you were raised on. Always be humble. It is what makes us human.’ You hold her words sacred. On the bus ride to the capital city, you do not complain when the man sitting next to you opens a box of Hungry Lion and crunches the bones. You surreptitiously push the window a little wider when he cracks the first of three boiled eggs. And you do not refuse when a young woman asks to put her toddler on your lap—for just a little while—so she can rest a bit, she explains. It is well, you think. You will soon board an aeroplane to America.

But America is too much everything for you. On the day you arrive you are taken to a restaurant where you are served a hamburger so huge you need to grab it with both hands and open your mouth so wide hippopotamus-like to take a bite of it. On the streets, food-turned-garbage, overflows from bins. The apartment in which you lodge gives you no respite. All night traffic roars past your door. The mabele your mother had snuck into your suitcase finishes and you fail to find it in the ethnic section of the grocery store. You hear your grandmother saying the reason for her good health is a bowl of mabele every morning.

How you ache for your mother who speaks in whispered tones, whose strength shows in how she carries herself upright—just as she did when she balanced a bucketful of water on her head. Her back was strong from carrying you and your sisters on her back as she worked. All you want is to complete your studies and return to the home you have been raised in. You nod and smile the kind of smile that tires your facial muscles when your landlady asks you, for the umpteenth time, eyebrows raised, if you are really sure you want to return to Africa?

You are savouring the last shreds of the Air Botswana biltong snack as the aeroplane prepares to land in Gaborone. Forehead pressed to the window; you scan the ground for familiar landmarks: the Notwane dam is there—at least the wall is visible but it holds no water; the once shiny Onion Tower is rusted; Capitol Cinema—razed to the ground.

When you arrive back in the home you grew up in, wood smoke from the outside fire meets you. The aroma of seswaa and phaleche and magwinya that your mother has cooked for you the old-fashioned way reaches you and you clean your plate. But out of the corner of your older, more-seeing eyes, you sometimes catch her resting her hands on the table as she inhales deeply. You feel the weight of her exhaustion bearing down on her. You wonder if it is sadness that has creased the corners of her eyes. The callousness on her hands scratch against your cheeks when she cups your face.

It strikes you how much of your mother there is in you: teeth that jostle for space in your mouth, shoving some out of alignment; how you tilt your head when you do not agree with something that is said, but cannot find gentle words with which to say no. And many times, people who telephone her tell you how your voice deceives them when you say hello.

But you want to be different from them.

Standing in front of the mirror, you think how blessed you are to have inherited your mother’s blemish-free skin and smile as you tint your lips red. You run an emery board across your nails and shape the ends into crescents. And then you paint berry-coloured polish on them. Your eyes meet your mother’s as she looks at you and that worry line furrows between her eyes. You hear impatience in her voice as she hurries you up because she says you’re taking far too long in the bathroom and she chides you for your vanity. But you wonder if you do not detect the slightest hint of a smile as you say goodbye as you strut out of the door.

You vow that when you have a daughter of your own, she will not become you, or your mother or your mother’s mother. You will bestow upon her a great name, a name that you would have given to yourself if you had had the choice: Toro—so that she dreams—big dreams. And like Setswana says, leinalebeseromo, she will become her name and shatter the mould that has been cemented in the language of tradition. And though you will repeat to her, the words that were said to you when you were just a little girl: mosaditshweneojewamabogo—that the beauty of a woman must show through her deeds—in how well she kneads the dough for the magwinya she fries and how smooth and without lumps her phaleche must be and in the fine lines her grass broom leaves in the sand when she sweeps the yard and you will say to her, her name should never fall carelessly from people’s mouths, you will also tell her that she must be more than her hands—that you did not try to walk a different path for her to simply be her hands.

You will make sure that she becomes more than her hands.

- Wame Molefhe is writer from Botswana. Her fiction has been published in local and international journals, anthologies and online. She is the author of Just Once (Medi Publishing, 2009), a children’s collection of short stories, and Go Tell the Sun (Modjaji Books, 2011). ‘Blood of Mine’, a story from this book, was recently adapted into an opera and performed at the Artscape Theatre in Cape Town. Molefhe has written a column for the New Internationalist of London and travel writing for television and radio.

Wow Wame. I am so proud of you.

I love you, Wame.

This is so simple, such a simple story and yet it is so moving. The weight of thousands of years of womanhood, of mothers and daughters, of women’s dreams for their girls condensed beautifully into so few words… Powerful stuff Wame. Applause.

As a motswana i do identify with the contents regardless of gender

As a young Motswana lady who is finding her own path in life, this resonated with me. There will always be a need to shatter the mould that was cemented in tradition. Thank you so much for this Wame Molefhe. You truly are an inspiration.

Beautiful…simple but resonates so deeply.

Beautiful! ?