Zukiswa Wanner is starting her own publishing company, with a focus on marketing and selling books throughout Africa.

Wanner will launch Paivapo with a reissue of her own work, after which she will start accepting manuscripts from up-and-coming writers. She sat down with The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec to outline her plans.

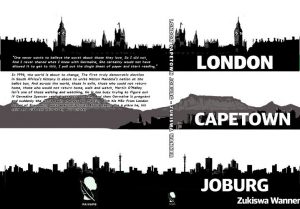

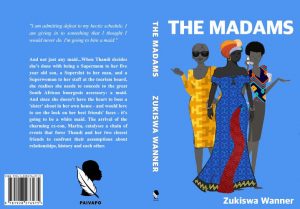

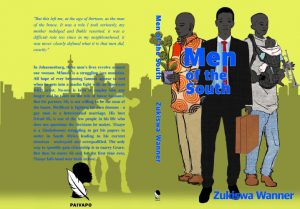

Wanner was born in Zambia, to a South African father and a Zimbabwean mother, and now lives in Nairobi, Kenya. Her debut novel, The Madams, in which a middle-class black woman decides to hire a white maid, was published in 2006, and shortlisted for the K Sello Duiker Memorial Literary Award. Her next book, Men of the South, was shortlisted for the Herman Charles Bosman Prize and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book (Africa Region). Behind Every Successful Man (2008) and the satirical non-fiction Maid in SA: 30 Ways to Leave Your Madam (2013) followed, before 2015’s London – Cape Town – Joburg, which won the K Sello Duiker Award. In 2014 she was named on the prestigious Africa39 list of trendsetting Sub-Saharan African writers under forty.

Wanner is currently on a Johannesburg Institute of Advanced Study (JIAS) fellowship, along with The JRB City Editor Niq Mhlongo. She and Mhlongo are also celebrating the publication of their new books, Hardly Working: A Travel Memoir of Sorts and Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree, with a series of events and launches throughout South Africa.

Event details

4 May: Cape Town, The Book Lounge

5 May: Cape Town, Molo Mhlaba (you are invited to buy a book to donate to the school)

10 May: Johannesburg, University of Johannesburg, with Niq Mhlongo

12 May: Johannesburg, Kingsmead Book Fair

20 May: Johannesburg, Walk My Jozi

23-24 May: North West Province, with Cynthia Jele, Niq Mhlongo and Fred Khumalo

26 May: Northern Cape, with Cynthia Jele, Niq Mhlongo and Fred Khumalo

2-4 June: Nelspruit and Swaziland, with Cynthia Jele and Niq Mhlongo

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: The first question I want to ask is quite broad: why have you started your own publishing initiative?

Zukiswa Wanner: It’s got a very broad answer as well. We’ve got some really brilliant writers in this country, but one of the things that has saddened me is that on the rest of the continent people don’t know South African writers. If you remember I wrote about this in an article some months ago in the Mail and Guardian [‘Writing’s on the wall for parochial SA publishers‘]. However, when I give people books by South African writers, they are impressed and it’s a revelation, they think they are brilliant.

I’m lucky to have been given a platform by the Goethe-Institut Nairobi, who gave me a bit of funding to curate a programme called Artistic Encounters, which brings South African writers into the Kenyan space, so that they can become more well known there. I always pair them with a local artist: for the very first one I had Koleka Putuma on stage with Victor Ehikhamenor, and he was drawing his interpretation of her poetry. People didn’t know who Koleka was, they were coming to see Victor Ehikhamenor. But afterwards her books just flew off the shelves. We also had Angela Makholwa, the South African–German poet Philipp Khabo Koepsell, and Lola Shoneyin, who needs no introduction. Her book The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives was performed by Maimouna Jallow, a Gambian actor who stays in Kenya. It was an experimental series, but it went very well, and the Goethe have allowed me a second season. This year we’ll have Yewande Omotoso, Niq Mhlongo, Dami Àjàyí, Pede Hollist from Sierra Leone. It’s trying to get people to see that there’s exciting African literature that they may not be aware of. Generally people assume Nigerian literature is African literature, and Nigerian literary spaces are very vibrant, but there’s also a lot of other stuff going on everywhere else.

So one of my big motivators was getting my friends’ works known throughout Africa! But of course I’ve got my rights back for all my major books, apart from Hardly Working, which has just been published by Black Letter Media, so I thought I would start there.

The JRB: How did you go about getting your rights back?

Zukiswa Wanner: I’m very strict. I read my contracts. What I generally say to the publisher is, after the initial print run, if you don’t print after a while, maybe after a year, kindly give me my rights back. And I think that’s reasonable, because it means that you don’t feel you can sell this title any more, but I feel that perhaps I can. Whenever I do a contract I make sure I have this little clause in it. Similarly I never give my publishers international rights, I just give them CUSA rights, common union of Southern Africa rights.

The JRB: I think a lot of authors don’t realise they have this power. Did someone advise you when you were just starting out, or did you do your own research?

Zukiswa Wanner: No, I gave world rights for my first book, The Madams, and my royalties were crap too. That’s when I learnt the importance of consulting with established writers because you’ll end up learning quite a bit. So before you sign on the dotted line, find out: is the contract okay, is it okay to give world rights, is this royalty fee okay, what is the publisher’s marketing plan for your work? It’s appreciated when you write a good book, but it doesn’t make a lot of sense if people don’t read it, or don’t know it exists. When a publisher says they are going to publish you, don’t get so excited that you allow everything. If a publisher is interested in your manuscript, chances are high that another publisher will be interested in it as well.

The JRB: So it’s a creative process but it’s also a business.

Zukiswa Wanner: That’s what I’m interested in, and that’s why I’ve started Paivapo. What I’m starting with is republishing my books. The Madams is twelve years old, and so when I read it again, for the first time in ages, I was cringing. So I’ve done a re-edit of that, and of Behind Every Successful Man. I may do a light edit of Maid in SA. But Men of the South and London – Cape Town – Joburg will probably remain as they are. By December I would like to produce a box-set of all my books.

After that, I’ll look around for funding to move forward. Funding permitting, I’m looking at publishing two books, three maximum, per year. What I’d like to do with those, my little fantasy, is to get the books translated into Portuguese and French for the Lusophone and Francophone markets. And then I’m going to market the hell out of our stories.

The JRB: What about African languages? Swahili?

Zukiswa Wanner: I’ve thought about Swahili and Hausa in particular, but it will come down to the cost.

The JRB: What else do you plan to do differently from what you’ve seen in traditional trade publishing?

Zukiswa Wanner: In the last few weeks, Niq [Mhlongo] and I have been getting on the road, going places, and saying ‘these are our books and we’re selling them’. We got on a bus and went to Zimbabwe, for example, and had two book launches there—one at Petina Gappah’s house, interestingly enough.

The JRB: Where did the funding come for this tour?

Zukiswa Wanner: From our pockets. We said, let’s do this. It’s painful, obviously, because you’ve got bills to pay, but it doesn’t make sense to have a work and not market it. With Kwela, Niq’s publisher, one of the lovely things is that they’ve agreed to a road trip. So they’re going to help fund our trip to the North West, with me, Niq, Fred Khumalo, Cynthia Jele, with our new books. Essentially this is what we were doing, and it’s the vision we had for Read SA back in 2009, 2010.

The JRB: How are the sales?

Zukiswa Wanner: I think Niq and I are both doing very well with sales. Niq is going to be reprinting just now, and I’m in my second reprint for Hardly Working. We’re doing well.

The JRB: You’re publishing house is called Paivapo, Shona for ‘there was’. Can you tell us a little bit about the name?

Zukiswa Wanner: When you are telling a tale in Shona, you begin with ‘paivapo’, which is the equivalent of ‘once upon a time’, and then the kids respond ‘dzepfunde’. That was a little nod to my mom. Our world is pretty patriarchal, and I get into spaces where people say ‘Zukiswa Wanner is a South African writer’, which I am, because my dad is South African, but people also forget that my mom is Zimbabwean.

The JRB: Your redesigned covers are slightly different to the originals, why did you decide to change them?

Zukiswa Wanner: I wanted them to maintain the same colours, so it doesn’t jar for people who are familiar with my work. I wanted them to be the type of covers that if someone sees them, they want to pick them up. I wanted a rebrand.

The JRB: What kind of manuscripts are you going to be looking for?

Zukiswa Wanner: I’m going to be looking largely for fiction. With non-fiction I would be looking for something that would be easily marketable to the rest of the continent. I think fiction speaks more to the rest of the continent and everybody else than non-fiction does, most of the time. Take The President’s Keepers, would someone in Zambia care about the president’s keepers in South Africa? I also really wish I could do poetry, but, eish, I don’t know. There are certain poets, Koleka for example brought me back to poetry, and Dami Àjàyí is amazing, but they are such big names that they probably wouldn’t let me near their stuff.

I sit on the board of Aké Festival, for example, and fiction sells like crazy there. And when you go into a bookstore here and see Leye Adenle, Lola Shoneyin, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s Dust, that’s not because there’s not non-fiction in those countries.

Angela Makholwa’s most recent novel The Blessed Girl focuses on blessers and blessees in South Africa. So when she came to Kenya for Artistic Encounters in November last year, I sat her down and said I need you to watch something on YouTube, and I showed her an interview with this woman in Kenya called Vera Sidika, and she has done the butt implants, breast implants—she’s a blessee. In Kenya they are not called blessers and blessees, they are called sponsors and sponsees. But her book just resonated with people in Kenya, with the crowd, and we were like, wow.

The JRB: And yet that’s a book that is unlikely to get a UK deal, so unless you’re facilitating that contact, it’s not going to happen.

Zukiswa Wanner: Exactly. It’s happening, it’s conversations we are having, in Kenya, in Ghana, in Congo, in Uganda, young women are going through those situations. But maybe the book is not going there. So it needs to go there. People need to know that this book exists.

The JRB: What do you see your role as? Editor? Talent scout?

Zukiswa Wanner: I know my limits. One of the lovely things with The Madams was that Michelle Matthews from Oshun Books read the manuscript as a publisher and she gave me feedback before she even assigned me to an editor. Not nearly enough publishers read as much as they should. I would like to be able to an initial edit for the writer, mostly content, less language. I personally don’t think that any book that has not gone through two or three edits should be published. Then, after the manuscript has come back, we can send it to an editor, we can think about cover designers, and so on.

The JRB: Do you think you’re able to do this because you have a brand of your own? Do you think you could have gone this way when you started out writing, or did you have to learn a lot first?

Zukiswa Wanner: I needed to learn. I wouldn’t have been able to do this without the knowledge that I know, without the gaps that I see. One of the things that has been very helpful is that I left home. Leaving South Africa allowed me to see what was happening out there. I kept thinking, I need to get my books to the rest of the continent, I want to see how to do that. I’ve always had that desire and that wish.

It’s an interesting dynamic. Everybody thinks South Africa is the America of the continent, we are very insular. And when we go out, we go to the London Book Fairs, the Frankfurts, our publishers don’t think, maybe it’s worthwhile to go to Aké Festival, to Writivism, to the Algiers book festival, there’s Étonnants Voyageurs, a lovely literary festival that Alain Mabanckou does in Congo-Brazzaville, maybe it’s worthwhile to go there. We don’t think about the possibilities of what is happening on the continent. But interestingly enough a lot of our literature resonates with this continent. I often see publishers in Western countries get into spaces where they want a certain narrative about Africa, but a lot of stories that are being written here in South Africa, a lot of the stories that resonate with the rest of the continent, are unapologetically about us, with all our flaws, they are not the same narrative of somebody in a village. So the market is there. But perhaps some of our publishers are not thinking about it. I don’t know if they are pushing the narrative that Africans don’t read, or what it is.

The JRB: It seems most of the books that get spread around Africa go via the UK or the US. So there’ll be a UK deal for a Kenyan book, and that’s how South Africa gets the book. It’s not us talking to each other.

Zukiswa Wanner: Exactly. Except now with Pan Macmillan and Cassava Republic, who have done a really great job. I love the idea that, for example, I was telling people how absolutely and totally brilliant Season of Crimson Blossoms is, and people could access it.

The JRB: I love that book. I was lucky enough to interview Abubakar Adam Ibrahim when he was in South Africa last year.

Zukiswa Wanner: It’s still one of my most gifted books.

The JRB: Would you be bringing books the other way?

Zukiswa Wanner: Of course, absolutely. I take advantage of my multinational position, I can sort out East Africa and Southern Africa, because I know a lot of the bookshops from here to Kenya, I know the people to talk to, to ask, can you stock this? We’ve also been having a bit of a chat with my friend Eghosa Imasuen, who’s just started Narrative Landscape in Nigeria, similarly with Lola Shoneyin’s Ouida Books, who published Stay With Me in Nigeria, both of them are writers and they’ve started publishing houses because they also feel that there is something, perhaps, that we can do better, that the publishing industry can do better, for writers. We understand the discomfort that a lot of writers have, and what they want.

The JRB: Finally, can you tell us a little bit about the novel you’re working on now? I believe it’s historical fiction.

Zukiswa Wanner: It delves into South African history, and the common thread, which seems to be the common thread with all my work, is identity. A young man grows up as a white boy, but he’s got a black mother and nobody knows. He ends up becoming an academic and sits on the apartheid racial classification board. That’s about as much as I can give away now. But Sol Plaatje makes an appearance, somewhere. I’m having a blast with it. JIAS is amazing and it’s been great to have the space to do research, and to use the UJ library, and also to do readings and book tours for Hardly Working in the SADEC region in a way I wouldn’t have been able to if it had come out while I was in Kenya.

6 thoughts on “[The JRB Daily] Exclusive to The JRB: ‘I’m going to market the hell out of our stories’—Zukiswa Wanner reveals the details of her new Africa-focused publishing company, Paivapo”