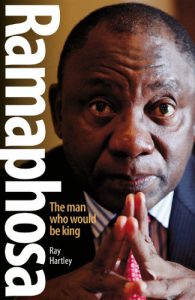

The JRB presents an excerpt from Ramaphosa: The Man Who Would Be King by Ray Hartley.

Ramaphosa: The Man Who Would Be King

Ray Hartley

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2017

Ready to lead?

Is Cyril Ramaphosa the man to lead South Africa out of its political and economic crisis? South Africa’s core problems are simple, but the solutions are complex. This is what Ramaphosa will have to confront.

Twenty-three years after the advent of democracy, South Africa’s democratic governance system is buckling under the weight of serious abuse. Descriptions of how the state has been captured are no longer the preserve of conspiracy theory. They have been the subject of serious academic study, of a book and of a detailed report by the Public Protector.

A decade of systematic state capture under Jacob Zuma’s presidency has chewed its way through the administration. Ministers beholden to the Gupta family—or to other private causes—have bent government spending away from delivering essential services to citizens and towards massive accumulation. The problem is not only at ministerial level, but includes government departments and the state-owned enterprises, where captured officials have diverted vast amounts of procurement in the direction of private companies allied to Zuma and the Guptas. The cronies are everywhere, concealing themselves behind a charade of governance while contributing to the enrichment of the few at the expense of the many. Ramaphosa’s primary task will be to remove this corruption from the system, root and branch. To do so, he will have no choice but to alienate a large section of the ANC—that section which has benefited from the looting through its association with Zuma and state capture. Is Ramaphosa capable of doing this?

One thing is certain: Ramaphosa has no association with any of the corruption scandals that have plagued South Africa. It is a remarkable fact that his name is not mentioned once in Andrew Feinstein’s 672-page magnum opus on the global arms trade, The Shadow World. His name has not come up in the hundreds of thousands of leaked Gupta emails, which have provided so much detail on the minutiae of corruption and state capture.

But the years he spent at Zuma’s side, playing the ‘inside game’ suggest that he is more comfortable as a powerful insider than as a radical reformer. There are signs, though, that Ramaphosa is breaking this mould. He has become more vocal about state capture and corruption, calling for those responsible to be jailed and for the money taken to be returned. But, should Ramaphosa win the ANC’s nomination to become president in 2019, will he see through this agenda or will he seek to accommodate the losers in order to prevent the ANC from falling apart?

Ramaphosa’s only political option will be to act aggressively against those who have had their snouts in the state capture trough. Failure to do so will lead to a continuation of corruption and the demise of the ANC. To accomplish a clean-out of these proportions, he will face a massive challenge. He will have to take two steps.

First, he will have to establish a credible, independent commission of inquiry into the wrongdoings of the Zuma era, one with broad terms of reference that will lead to the exposure of corruption in all its ugly detail. The second step, which he would have to begin while the commission carries out its work, is a far greater challenge.

Zuma has survived as long as he has because he had his priorities right. Before full-blown state capture was implemented, he pulled the teeth from the police and the prosecution service. He saw to it that the Scorpions were disbanded and replaced by the Hawks, which report to the police. He then saw to it that the Hawks—and the police—were headed by a succession of lackeys who removed from these institutions the capacity to vigorously investigate corruption by himself and his cronies. He also turned the NPA into a body politically beholden to himself, and so it ceased to meaningfully prosecute cases of corruption. Once this was done, the looting began in earnest and there were never any legal consequences.

Ramaphosa will have to rebuild the police, re-establish an in-dependent corruption-fighting organisation with the powers that the Scorpions enjoyed and rebuild the prosecution service under a credible leader. To achieve this, he will have to remove a cadre of corrupt and incompetent leaders from the security services. More than this, he will have to see to it that they are held account-able for their lapses, which allowed state capture to take place. Once the country has a clear view of the corruption landscape from the commission of inquiry and a functional criminal justice system, it will be in a position to begin the trials of those who were part of the state capture programme. These may take years and will, no doubt, be accompanied by a great deal of aggressive politicking within the ANC.

- Ray Hartley worked as an administrator at the Codesa negotiations, which ended apartheid. He was the founding editor of The Times and editor of The Sunday Times from 2010 to 2013. He is author of Ragged Glory: The Rainbow Nation in Black and White and editor of the essay collection How To Fix South Africa.