TO Molefe believes Raoul Peck should have claimed I Am Not Your Negro as a new, original work, not as James Baldwin’s unfinished book.

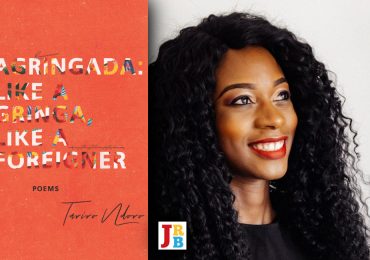

I Am Not Your Negro

I Am Not Your Negro

James Baldwin and Raoul Peck

Penguin Classics, 2017

It has been exactly a year since the full release of Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, right at the beginning of February’s Black History Month commemorations in the United States (and elsewhere). The highly ambitious work is both a documentary film and a book, based on notes James Baldwin began to cobble together in 1979, at the age of fifty-five. The Harlem Renaissance writer hoped these would lead to a book that unveiled American racism in all its grotesqueness as a system, through the lives and assassinations of three of his friends—Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr and Malcolm X.

He described the endeavour to his literary agent as a ‘journey’, adding that he could not predict what he was going to discover along the way nor what such discoveries would do to him. He died eight years later, and as narrator Samuel L Jackson says at the beginning of the film, ‘Baldwin never got past his thirty pages of notes entitled: Remember This House.’

Peck’s book, while mostly a text-and-images script of the film, also includes his motivations and thinking. It becomes clear in the first few pages that ‘based on’ is probably the wrong phrase to describe the work’s relation to Baldwin’s notes, which were rough and unfinished. In the first chapter of his book, Peck writes that he believes his job was to find Baldwin’s unwritten book from the notes, and the late, great author’s other writings.

In other words, I Am Not Your Negro is supposed to be Remember This House—or at least what Peck professes is a faithful representation of Baldwin’s thoughts, style and choices.

To those who have not experienced the work this claim might seem presumptuous—bordering on arrogant. Which might explain Peck’s trepidation. A seasoned filmmaker, Peck was probably in the final stages of post-production when a Baldwin-related bunfight broke out in 2015, after Toni Morrison, having read an advance copy of Between the World and Me, was interpreted as anointing Ta-Nehisi Coates as ‘the new Baldwin’. What Morrison actually said was that Coates ‘filled the intellectual void’ that had plagued her since Baldwin died. It was an expression of personal feeling that, through the fast, furious fingers of social media, was responded to as though it were an objective statement of fact.

To claim that what a person says a book meant to them and what it made them feel is ‘wrong’, and to present yourself as knowing the voids that plague that person and what fills them better than they do, is—in the absence of a Vulcan mind meld or Betazoid telepathic powers—laugh-out-loud absurd. But such are our times. ‘Why Toni Morrison (a literary genius) is Wrong about Ta-Nehisi Coates’, quick-with-the-whip public intellectual Cornel West began his Facebook status update. Then he proceeded to tear Coates a new one.

The hot, sweaty wrestling match that unfolded on social media and in opinion pages over who has credible claim to Baldwin’s intellectual legacy—which had observers reaching for popcorn, as the Twitterati would put it—was reminiscent of the catty spat that unfolded in South Africa’s Mail & Guardian newspaper in 2012 over who the rightful heir was to another fiery intellectual, Bantu Stephen Biko. The exchange, which took place between Andile Mngxitama (dubbed ‘vice Biko’ for his bellicose responses to anyone who dares claim to know the Black Consciousness founder’s ideology better than he) and University of Cape Town professor Xolela Mangcu, over the former’s review of the latter’s biography of Biko, was fun to watch but ultimately meaningless. Like Baldwin’s, Biko’s ideas remain relevant. But ultimately Mngxitama versus Mangcu left us none the wiser on how to use Black Consciousness as a liberation framework in South Africa today.

Writers and filmmakers, like other artists, routinely trawl the archive for events and figures whose life and work move them. This is a normal part of the creative process, as are impostor syndrome and insecurity, which can cause the creator to cling to the original work to validate their own, even if they have created something entirely new. Or perhaps hiding the new work behind the work of an established historical figure is a shield against attack from less generous peers who will read inspiration as imitation or outright fraudulence.

After Coates was attacked merely because Morrison said his words filled, in her own intellectual universe, the void created by Baldwin’s passing, can you imagine what must have been going through the mind of the man who set out to ‘find’ Baldwin’s unfinished book? Doubt. Weight of the (ir)responsibility. Fear of reprisal for possibly being seen to be a self-declared new Baldwin—or, worse yet, for corrupting the respected writer’s ideas.

‘I hope I have not betrayed a man who has accompanied me from very early on, every day of my life, as a brother, father, mentor, accomplice, consoler, comrade-in-arms—an eternal witness of my own wanderings,’ Peck says at the end of his notes on the writing process.

In the work, Peck is at pains, in an age of personal essays and selfie-style documentary filmmaking, to disavow his hand. These are Baldwin’s words, he urges in his brief contribution at the beginning of the book. These are his ideas, he says, hand on heart. In the film, Peck is nowhere to be seen. Instead viewers are assailed by a masterfully curated selection of visuals from the Civil Rights Movement, interviews with and speeches by Baldwin, clips from movies and TV shows, and the voice of Jackson holding it all together, using Baldwin’s words.

The effect is profound. Only the most hardened cynic can claim not to have been battered and bruised by the experience. Battered, bruised, but shaken awake to how little has changed in America—even if you thought yourself woke before, even after the election of a black president. Awakened to, as Baldwin put it, the fact that white people found it necessary to invent the concept of a ‘n****r’—the key words being ‘necessary’ and ‘invent’. He refused the insult because he knew it had nothing to do with him and everything to do with those who hurled it. He marked the epithet ‘return to sender’, with a note suggesting that white people find out why they felt it a necessary word.

Baldwin, of course, knew the answer. His was a provocation for the humanising self-reflection he saw as critically lacking in white America: ‘White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank,’ he wrote. And power, to be accepted, needs rationalisation. It needs some basis—which history tells us is often false—to justify why those who wield it have legitimate claim to do so.

‘N****r’ (and its polar opposite, white) was necessary to rationalise the enslavement of the people known today as African-Americans. Its continual reification, the latest seeing the return to the public eye of white supremacist groups and the election of a president more overtly racist than his predecessors, has been necessary to justify the violent oppressions and social and economic outcomes that sprang forth, accumulated each year and rolled up with scant correction into America’s general ledger; from the massacre of Native Americans to the present day’s police brutality. It has been necessary to justify the American Dream—built on a foundation of nightmares visited upon countless people, including the civilian victims of the modern day’s terrifying war on terror.

This is among the late author’s greatest intellectual contributions. He returned to it several times over his career in speeches, debates and essays. (See, for example, this piece published in Essence magazine in 1984.) It is also the source of the title of Peck’s work and, fittingly, its narrative thread and closing sequence—and it makes I Am Not Your Negro an exquisite standalone work that pays homage to Baldwin, a collage whose whole is far greater than the sum of its parts and whose messages are as needed today as Baldwin’s were in his day. And it is Peck who made it happen, not Baldwin.

Other than the real fear of being treated as Coates was, there was, with the benefit of distance and hindsight, no need for Peck to present his work as an attempt to find Remember This House in Baldwin’s notes and other writing. Even if that’s how it started out, his libretto clearly became something else—a new, original work. Presenting it as Baldwin’s unfinished book opens up I Am Not Your Negro to valid critique that could have been anticipated and likely avoided.

At a private screening of the film in Johannesburg, before its limited run in three cinemas in South Africa late last year, a young queer man stood up during the discussion afterwards bristling with rage. He said Peck erased Baldwin’s sexuality and his work on sexuality and that, through that act, I Am Not Your Negro gave primacy to race and neglected the particularities of how black women, queers and trans people are brutalised by both white supremacy and heteropatriarchy.

It was a fair and accurate statement (even if its imputation of ill intent on the part of Peck is unfair without more information). It is also worth adding that the film failed to tackle American imperialism as an anti-black force around the world, including in Peck’s native Haiti.

I Am Not Your Negro does indeed contain a whiff of anachronism as it tries to relate Baldwin’s ideas to the present. The young man’s comment also brings to mind Bayard Rustin, a gay man who was Baldwin’s friend and one of Martin Luther King Jr’s closest advisers.

How, if at all, in his journey through King’s life and assassination in Remember This House would Baldwin have handled Rustin’s sidelining in the Civil Rights Movement as a result of his sexuality and his criminal conviction for having sex with another man in a parked car? If Baldwin didn’t write about it in his notes or the other writing Peck had access to, does this mean he would have made the same choice in Remember This House?

Only Baldwin knows the answers and, sadly, he is no longer around to tell us.

If Peck had braved the hypercritical yet often banal scrutiny of the social media era and claimed in the production process I Am Not Your Negro as his own original work, inspired by Baldwin’s notes, would he have found a way to include in his ‘funky dish of chitterlings’ the demands for justice for the specific oppressions experienced by black women, queers and trans people? Would he have found a way to be critical of American imperialism? Would he have wanted to? Would he have been allowed to without being deemed another usurper of Baldwin’s throne? Would it have taken the work from exquisite to extraordinary?

An optimist hopes so.

- TO Molefe is an essayist and writer based in Johannesburg. Follow him on Twitter.