Niq Mhlongo recounts his literary travels to Accra, Ghana—in 2008, for the Pan-African Literary Forum, and in 2017 for the first ever PaGya! Literary Festival.

Ghana, 2008

We arrive at Kotoka International Airport in Ghana on a South African Airways flight from Johannesburg around midnight, South African time. It’s only ten o’clock in the evening in Ghana. The Ghanaians, like the British, are two hours behind us. The six of us, Vonani Bila, Sandile Ngidi, Kea’ Modimoeng, Siphiwo Mahala, Kitso Kgaboesele and I, will be joined the next day by Zukiswa Wanner, Dumisani Sibiya, Uncle Ronnie Govender, and Prof Keorapetse Kgositsile. We’ve been invited to participate in the Pan-African Literary Forum in Accra. Our generous sponsor is South Africa’s Department of Arts and Culture.

As I emerge from the plane the humid air hits me, making me sweat. We left South Africa in the middle of a cold winter, on the fourth of July, but here in Accra it feels like a very hot summer night. At the immigration office, the friendly man who stamps our passports asks us where we are from. Behind me, my fellow scribe and friend Sandile Ngidi tells him that we are South Africans.

‘Ahhh, Shaka Zulu! You are the warriors!’ the officer says loudly. He smiles and adds: ‘Please give me anything from your heart. A gift from your beloved country, South Africa.’

Ngidi searches his pockets. He gives the officer a fifty-billion Zimbabwean dollar note that our fellow writer friend, Chris Mlalazi from Zimbabwe, had given him onboard. The officer is a very happy man. He kisses Ngidi’s hand and blesses him in a local language. It clear he does not know the value of the Zim dollar. Chris has already told us that the amount is equal to about ten South African rand and that it can only buy one quart of beer. Earlier, on the plane, Chris had been regaling us by making fun of the worthless currency. He even told the unsuspecting beautiful South African air hostess that he was a ‘quazillionaire’ by showing her the five-hundred-billion Zim dollars that he carried in his pocket. The air hostess fell for Chris’s charm when he offered her a pink fifty-billion-dollar note. That had worked miracles for us. For the duration of that six-hour flight the air hostess gave us round after round of gin and tonic—even after the bar had closed.

The strange thing about Kotoka International Airport is that if you are not travelling you are not allowed inside. Perhaps it’s because it’s so small, compared to the sprawling OR Tambo International. We push our trolleys outside where everybody is waiting. We see two guys smiling and holding a piece of white paper on which is written: PALF-SIPHIWO. Looking at their genuine smiles, I’m convinced that everyone must like smiling here in Ghana, from the airport officials to the ordinary people. The two guys are our drivers, tasked with taking us in two cars to the Protea Hotel in East Legon. Chris decides that he will crash with me at the hotel as there is no one to pick him up.

As we drive, our driver points at three massive houses along the road. ‘This is Abedi Pele’s house. That is Michael Essien’s mansion. Over there is Stephen Appiah’s house. Most rich people of Ghana live here.’

Even by the dim light of the streetlamps, it’s clear that the houses he is pointing at are as big as the Protea Gardens shopping mall back home in Chi Town, Soweto. From what he says I gather that East Legon is the Sandton or Camps Bay of Accra.

We check in at the Protea Hotel and gather at the dinner table where I have lamb chops and jollof rice. When others talk about sleeping, Chris and I go to the hotel bar for nightcaps, but we’re also tired and don’t stay long.

The following day is Friday and I miss my breakfast because of babalaas-induced oversleeping. Chris has already left for his accommodation at the New York University campus in Labone. After showering I go down to the restaurant to meet the others. While we are still wondering what food to order, a tall dark guy with nicely trimmed short hair comes over to our table. He is wearing a white kurta and a wide Ghanaian smile, and introduces himself as Noah. He tells us that he has been sent by the South African High Commissioner in Ghana to be our driver for the duration of our stay. This is great news: we’ll have someone to drive us around in an air-conditioned minibus in the hot and humid weather. Noah tells us that he is Hausa and Muslim, from the northern part of the country. Unbeknownst to us we shall have to pay a very high price for the air-conditioned trips we take, and for Noah’s smiles. Everything in Ghana works on ‘commission’, you see.

In the afternoon, we ask the ever-smiling Noah to drive us to a restaurant away from the hotel. He recommends a restaurant that he knows at the Makola Market, a suggestion that appeals to us because we also want to buy cellphone starter packs. Noah seems to have the hots for Kitso, meanwhile. He smiles at her all the time, even when she’s not talking to him. I don’t know whether I should call it lust or love at first sight, but he even asks Kitso to come and sit with him in the front of the minibus. She obliges.

‘Have you been to South Africa?’ Kitso asks him as he drives on the busy street.

‘I don’t like you South Africans. You killed my friend Lucky Dube,’ he says without hesitation.

The way Noah responds I’m convinced for a moment that he must have shared a glass of wine with the late reggae king. Then I remember that he is Muslim, and must just be a great fan of Lucky Dube’s music. He opens the cubbyhole to take out a CD pouch, and for the rest of the journey he sings along to ‘Together as One’.

My observation since I arrived the previous night is that the most popular South Africans in Ghana are not Bafana Bafana’s soccer stars, as I would have imagined in a soccer-mad country. Instead, it seems to be Lucky Dube, Mama Miriam Makeba and former President Nelson Mandela. If you go to a pub in Ghana and they find out that you’re a South African, they will play Lucky Dube for you, I’ll bet. I heard his music constantly, blaring from cars and spaza shops.

‘You see here in Ghana we love peace. Why do you kill other African brothers in South Africa? Me don’t understand,’ Noah says, referring, not just to Lucky Dube’s murder, but the recent xenophobic attacks in South Africa. ‘Here in Ghana a brother is a brother. We live with him. You are my brothers. But I don’t like South Africa and Nigeria. Too much crime there. But I like you, sister,’ he smiles at Kitso besides him. ‘And you, brothers,’ he adds, turning to look at us in the back of the minibus.

In Ghana, as in most European countries, people drive on the right side of the road. Along almost all of the main roads you’ll find a bright yellow advertisement for MTN, the mobile network company. It is as if MTN is the only such company in Accra. The meter taxis on the road are also yellow, as well as some minibuses.

‘Just have a look. South Africans are the new colonisers of Africa,’ teases Sandile Ngidi as we pass the Accra Mall, which has South African shops like Shoprite and Game—the only difference being that these shops also have bottle stores inside where they sell booze, even on a Sunday.

‘Just have a look. South Africans are the new colonisers of Africa,’ teases Sandile Ngidi as we pass the Accra Mall, which has South African shops like Shoprite and Game—the only difference being that these shops also have bottle stores inside where they sell booze, even on a Sunday.

People are selling all kinds of things on the road, but unlike back home, hawkers in Accra stand in the middle of the road when selling their wares. When the traffic lights are red, they knock on your window to sell you fried banana (plantains), water sachets and boiled groundnuts, among other things. Oh, and they also have those guys who insist on washing your windscreen, just like at Jozi’s intersections.

We arrive at the Makola Market forty-five minutes later because of the traffic. We park the minibus in the basement of some old building. The market is huge; it looks to be about ten times the size of Mary Fitzgerald Square in Newtown. Vonani and Kitso have cameras, but before they can click there is a loud protest from some women, who demand to be paid first. Kitso says something in Setswana, asking why she should pay to take the pictures of the street. But she ends up not taking those pictures.

We walk through the congested pavement where everyone seems to be selling everything. There are stands selling bras, underwear, sugarcane, peeled oranges, cheap soccer kits. There’s an air of capitalism and freedom in this market; I can tell by the way people are allowed to quench their diabolic thirst with beer on the street pavement without the police harassing them. Vendors are even allowed to sell beer on the side of the road from cooler boxes. Another thing I observe is that I haven’t seen a single Ghanaian smoking.

But don’t be fooled. Ghana is too expensive if you don’t get the right locals to show you around. So far it’s the only country I’ve been to in Africa where an American dollar has less value than the local money. In 2008, one Ghana cedi will buy you one American dollar and five cents. Or maybe the rate is set that way because it’s obvious we are foreigners.

We stop by a vendor with a very small yellow container that has an MTN logo on it and buy starter packs from him for three cedis. After that Vonani suggests we taste some Ghanaian food. The ever-smiling Noah takes us to a nearby restaurant called The Last Supper. It’s like the fish and chips restaurant on Jozi’s Wanderers Street.

For the nineteen days that we are in Ghana, I never see any popular-brand fast food restaurant, like KFC, McDonald’s, or Nando’s. People here stick to their own food. All you will see are very small family businesses with biblical names such as God’s Will Restaurant, Jesus Is The Saviour’s Take Away, In God We Trust Meal, or The Last Supper Café, where you can enjoy a delicious meal of tilapia and banku (my and Volani’s favourite), barracuda, fufu, plantain or yam.

The thing I admire the most about Ghanaians is that they are still very communal. If you enter one of the small shops at night to buy a litre of bottled water for a cedi, you will find people sitting on a bench watching a Nollywood movie together, the volume muted. This happened to me on several occasions, and I found myself joining them, almost in a trance, standing in front of the TV set without even being aware that I was obstructing the other viewers.

At The Last Supper I’m feeling hungry and I order what Noah promises is the best Ghanaian dish: fufu, red soup and goat meat. Except for Kitso, who is a vegetarian, all of us order the same dish. While we are still waiting for our food, Noah excuses himself as it’s time for him to go and pray at the Mosque. He tells us he will be back in fifteen minutes, but before he leaves he stops at the kitchen. Everything works on commission, remember? Noah has brought guests to eat in the restaurant, so he has to be paid his commission. The same rule applies everywhere, even at hotels.

The food arrives forty minutes later and it’s good, but we give the waitress some ‘Mzansi medicine’ by complaining that the meat is too little: I have two pieces the size of my pinkie finger on my plate. She in turn gives us the ‘Ghanaian smile’ and says that if we come back the following day we will get more meat. The red soup is hot, and it seems I’m the only one that’s eating and enjoying it—courtesy of my babalaas.

In the evening there is a greeting and reception with the Pan-African Literary Forum faculty and staff at New York University in Lagone. There are readings by some extraordinary storytellers, Arthur Flowers and Nii Ayikwei Parkes. Professor Kgositsile Keorapetse, Dumisani Sibiya, Oom Ronnie Govender and Zukiswa Wanner have also arrived. The delegates are introduced, including Mama Ama Ata Aidoo, and the director of PALF, Jeffrey Renard Allen, who introduces me as the ‘following week’s professor’, to teach creative writing. Binyavanga Wainaina is also there and will teach the other creative writing class.

We leave the NYU centre around eleven in the evening, and Kitso suggests we should ‘have a feel of Ghana’. Her friend, Kobina, who she met while they were students at The University of London, is DJing at the Rema Bar. Kitso, Vonani, Ngidi and I decide to hire a meter taxi for fifty cedis. Later, when we pay five cedis to get back to the hotel in the early hours of the morning, we realise we were ripped off.

One thing that you have to know about most Ghanaian taxi drivers is that they are not that familiar with their city. Accra reminds me of Soweto, where a street name doesn’t help you much in terms of finding your way around. The only properly marked streets in Accra are the main roads, and people know their area through landmarks. For instance if you want a taxi driver to take you to the NYU center, you must add ‘in Labone by Chelsea Hotel, not very far from the South African Embassy’. But drivers will not tell you when they don’t know the place. They would rather get lost for two hours and charge you for their fault with a smile, which happened to us on many occasions.

After getting lost for about an hour, we finally arrive at the Rema Bar, which has a disappointing crowd of less than twenty people inside. But the music is good. Upon seeing us Kobina plays a maskandi tune by Phuzekhemisi called ‘Imbizo’. Ngidi opens the dance floor for us, and I show them my moves later when the old kwaito song by Tokollo Magesh featuring TK called ‘Number 1 Tsotsi’ plays. We leave at about four in the morning, my head spinning from the gin and tonic.

***

Nine years later, as I land at Kotoka International Airport on 20 October 2017, it seems that everything I knew has changed, except for the hot morning humidity. Unlike nine years ago, I’ve travelled light this time. My small backpack is filled with three days’ worth of clothes: a pair of jeans, takkies and a couple of T-shirts. My large backpack, which I’ve checked in, is filled with forty copies of my novel, Way Back Home.

Nine years later, as I land at Kotoka International Airport on 20 October 2017, it seems that everything I knew has changed, except for the hot morning humidity. Unlike nine years ago, I’ve travelled light this time. My small backpack is filled with three days’ worth of clothes: a pair of jeans, takkies and a couple of T-shirts. My large backpack, which I’ve checked in, is filled with forty copies of my novel, Way Back Home.

The airport looks bigger. Some of the buildings next to the airport that were under construction in 2008 are now complete and functioning. As I stand in the passport and immigration queue a voice comes over the public address system: ‘Please do not offer any airport officials any money as that is a criminal offence.’ The words are repeated over and over again. When my turn comes for my passport to stamped, I’m told I have to fill in an immigration form. I’m feeling very tired, after spending eleven hours on the Ethiopian Airways flight—five-and-a-half hours from Johannesburg to Addis Ababa, and another five-and-a-half hours to Accra—coupled with the time zone changes. The fact that I drank a few Habesha Cold Gold lagers on the flight possibly made it worse.

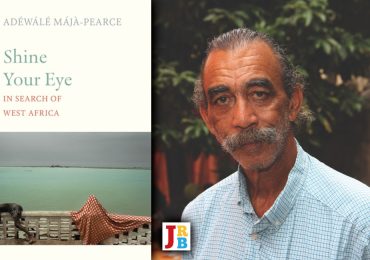

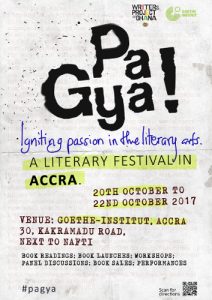

While filling in my immigration form I remember that I have forgotten my documents that show the details of my visit. All I can recall is that I’m invited to the PaGya! Literary Festival together with my old friend, the South African author Sabata-Mpho Mokae. My cellphone is out of action, so I can’t even retrieve the information sent to me by my hosts, Bernard Akoi-Jackson, Martin Egblewogbe and Lizz Johnson. But remembering their names is not enough to complete the form. All that comes to my mind when I try to recall the information are the names of participating authors, including Mama Ama Ata Aidoo, Chuma Nwokolo, Nii Ayikwei Parkes, Manu Herbstein, Adewale Maja-Pearce and Eghosa Imasuen.

While filling in my immigration form I remember that I have forgotten my documents that show the details of my visit. All I can recall is that I’m invited to the PaGya! Literary Festival together with my old friend, the South African author Sabata-Mpho Mokae. My cellphone is out of action, so I can’t even retrieve the information sent to me by my hosts, Bernard Akoi-Jackson, Martin Egblewogbe and Lizz Johnson. But remembering their names is not enough to complete the form. All that comes to my mind when I try to recall the information are the names of participating authors, including Mama Ama Ata Aidoo, Chuma Nwokolo, Nii Ayikwei Parkes, Manu Herbstein, Adewale Maja-Pearce and Eghosa Imasuen.

I decide to improvise. I have in my pocket a piece of paper with the details of my newly-acquired friend, Mazuri, who I met on the plane from Addis Ababa. Mazuri had told me he was a chief from a region in western Ghana called Esiama. He was coming back from Oman, where he had been on holiday; chieftaincy duties were calling him home. He had invited me to come over and attend a traditional ceremony, even offering me three beautiful brides if I were to write a story about it. This after I had told him that I’m a journalist. Who knows if I’ll ever take him up on his offer, but his contact details come in handy at immigration and I use him as my host. Everything else is in order, my yellow fever card and my visa, which I paid nine hundred rand to apply for in Pretoria. It is possible to get a visa upon arrival in Accra, but I’d been warned that it is expensive.

Outside the airport, the driver from Mahogany Lodge in East Cantonments, Kakramadu Links, is waiting for me with a sign that bears my name. It’s about midday and the traffic is heavy. We take about thirty-five minutes to get to the lodge, normally about a ten-minute drive. When I arrive at the hotel, a women from the festival, Beatrice, is already waiting for me. The short story writing class that I’m supposed to facilitate with Nii Parkes is already on. I have already read all nine short story submissions and made a few notes, so I drop my bags quickly and walk with Beatrice to the Goethe-Institut, where the festival is taking place. I’m carrying my backpack filled with my books, which I’m planning to sell at ten dollars or forty cedis each.

It’s about a five-minute walk from the lodge to the Goethe-Institut. Beatrice tells me that the workshop will soon break for lunch, so I decide I will attend after lunch and use the free hour to relax a bit. At the gate I meet Sabata and Eghosa and we decide to go together to the restaurant inside the Institut. (I met Eghosa in Lagos in 2010 when I was invited by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to facilitate the Farafina Creative Writing Workshop with Binyavanga Wainaina.)

The place is already buzzing with storytellers and story lovers. For lunch I settle for banku and tilapia, while Sabata, Eghusu and Chuma order banku and okro. We wash that down with a quart of Club Premium Lager, which fortifies me for my workshop session.

At two in the afternoon I take over from Nii to facilitate the workshop. Sabata has already arranged to go to the market to buy gifts with Jane, one of the festival assistants. The workshop ends at four, and I go back to the lodge to refresh. At six, Mama Ama Ata Aidoo is doing a reading, which is fully attended. She is accompanied by her daughter Kinna, who I meet for the first time.

The great thing about the PaGya Festival is that everything happens around one place—the sessions, the restaurant, the book stalls, the food stalls and the bar are all in the Goethe-Institut’s yard. Every night there is a beautiful performance of poetry and traditional storytelling that is accompanied by great African music. There are readings, book launches and discussions—as the first year of the festival it must be counted a great success. One of the highlights is the launch of Chuma’s latest novel The Extinction of Menai, which was packed out.

The great thing about the PaGya Festival is that everything happens around one place—the sessions, the restaurant, the book stalls, the food stalls and the bar are all in the Goethe-Institut’s yard. Every night there is a beautiful performance of poetry and traditional storytelling that is accompanied by great African music. There are readings, book launches and discussions—as the first year of the festival it must be counted a great success. One of the highlights is the launch of Chuma’s latest novel The Extinction of Menai, which was packed out.

My reading is on Saturday evening, and it is also well attended. I’m reading from my forthcoming collection of short stories called Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree, which is due out early next year. This is only the second time I’m reading from it, the first time being in Zurich at a writing workshop earlier this year.

On Sunday Sabata has a reading session and after that we go to the market on Osu Oxford Street where we buy some great Ghanaian fabric for ten cedis per square meter. Sabata and I also buy books to take back home at a much cheaper price than in South Africa, ranging from between ten and forty cedis (thirty to 130 rand). The best thing is that I went to Ghana with forty copies of Way Back Home and I’m leaving with only six—which have been pre-ordered by readers back home. I sold ten copies in two days at forty cedis per copy. The rest have been sold by the Writers Project of Ghana.

As I say goodbye to Accra on Monday morning, I am sure I’m going to miss this place. I will miss our nightly gathering at the Mahogany and the Goethe-Institut, where we talked literature, politics, law, corruption, economics, love and everything else. I will miss my banku and tilapia, the beautiful smiles of the festival staff, the smell of jollof rice and fried plantains, the Club beer, the book stalls, the heat and humidity, Eghosa’s laughter and stories, Sabata’s Coke addiction, Chuma’s graying hair, beard and commanding voice, Bernard wearing his beanie, Martin holding his Club dumpie, our friend Malva from Sweden, Adewale’s book reading, the cat that our friend Anne fed our sausage to, Nana Awere Damoah’s voice in the corridor, Kinna’s voice, Nana Asaase’s captivating Salaam poem. That’s my experience in Accra. Not even the pretty faces of the Ethiopian Airways crew on the return flight home can make me forget it.

- Niq Mhlongo is City Editor; his latest book is an anthology of short stories, Affluenza. Follow him on Twitter.