Author Zukiswa Wanner recounts high jinks and high drama on her way to Lviv, Ukraine.

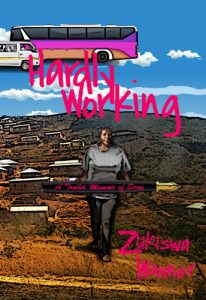

The following is an excerpt from Wanner’s new book Hardly Working: A Travel Memoir of Sorts.

Hardly Working: A Travel Memoir of Sorts

Hardly Working: A Travel Memoir of Sorts

Zukiswa Wanner

Black Letter Media, 2018

My late father studied journalism in Eastern Europe.

It had always seemed like a random choice to me when many other people I knew who studied in Eastern Europe had studied engineering or medicine. But an invitation to Eastern Europe was always going to be welcomed by me as it would give me the chance to see a place often closed off, and yet where my father and many of his friends had spent key parts of their lives. Going to Ukraine would also allow me to reconcile with my friend Nelly, one of the organisers of the Lviv International Literary Festival. In fact, it would be a reunion of sorts, as I met both Nelly and Peter, who had hosted me in Denmark, at the same time during the Cambridge Literary Festival in 2009.

Until the Friday before my departure, though, the entire trip was all still up in the air.

A visa for the Ukraine, had I been getting it in South Africa or Kenya, would have required that I set aside three weeks for the application. But I had failed to apply for it in Kenya or South Africa owing to a grueling travel schedule before I left the African continent. Nelly had suggested that I should not worry too much as I could get it in Copenhagen. I was not too sure. I was a very temporary resident in Denmark. I would be there for just three months, to be exact. Would I get the visa?

Nelly promised that she would get a letter from some official to ensure the visa was issued quickly. As soon as I arrived in Copenhagen, Peter started calling Nelly. Peter’s organisation, World Wide Words (WoWiWo), which was responsible for my Danish invitation, was also taking two other guests who required visas, so all three of us planned to apply together, with Peter’s assistance. Nelly was very laid back about it all, ‘Don’t worry, I will get it’. But Peter and I were worried.

On Wednesday, a week before the festival was due to commence, we got letters from the Mayor of Lviv. That very day, Peter drove me to the Ukrainian Embassy in Copenhagen. When we arrived, we met another member of our party who needed a visa.

We entered the Embassy.

Peter spoke in a very Director of WoWiWo voice, ‘We have this invitation to Lviv from the Mayor.’

The woman behind the glass looked at the invitation. And looked at us.

People who were born and grew up before the Berlin Wall came down, or who have ever watched Hollywood movies or James Bond flicks, where Eastern Europeans were always cast as the bad guys, would have identified this woman immediately. Her black hair was gelled and held in a chignon, which emphasised her cheekbones and made her either beautifully severe or severely beautiful, I could not say which. Less than thirty seconds later, however, I knew which it was when she said, ‘No. You need three weeks to apply with a passport from Africa. I cannot help you.’

Maybe it was those same Hollywood movies that made me do it but, in the absence of a nametag I nicknamed her Svetlana.

She passed on an application form to another member of our party, Omid, whose paperwork was apparently more acceptable than mine. She insisted, however, that she wanted the original letter from the mayor rather than a scanned copy. At this point in time, I resigned myself to not going to Ukraine. I figured it wasn’t a train smash, as it would give me more time to start writing, which was really the major reason why I had agreed to do the fellowship.

But Peter was not taking Svetlana’s injunctions at face value, so he called Nelly.

After explaining what had just happened, he looked at Svetlana and passed her his phone, ‘she wants to talk to you.’

Svetlana took the phone to a back room where, I assume, she was chatting with Nelly. When she returned, she handed over the phone, then called me over and asked me in English so clipped each word was as neatly stated as each hair on her head, ‘Have you filled out the application?’

No, I had not.

‘Okay, wait. I give you the application forms.’

It was an astounding transformation. I filled out the application forms and handed them back to her.

I also needed to submit two passport photos. Did I have any? I did not.

So she politely directed me to the closest place I could get passport photos. ‘We have thirty minutes still before we close, so you have enough time.’

I returned and submitted the forms and the photographs. I had not yet paid the visa fee, which had to be deposited into an account, but Svetlana said that was no problem at all: ‘You pay for the visa tomorrow and come back on Friday with receipt. You cannot come tomorrow with receipt. Tomorrow we deal with visa for the disabled. You visa will be ready on Friday.’ I was not entirely sure why she mentioned the bit about disabled people but there it was. Now I have valuable information about the Ukrainian Embassy in Denmark, but I am unlikely to use it, as I am unlikely to apply for a visa from there ever again.

What was miraculous though was that, after the conversation with Nelly, Svetlana was essentially telling me that she was going to process the visa before I paid the visa fee.

Later that day, Peter got a message from his sister that their mother had passed on. He departed with his family for his ancestral home in The Hebrides, Scotland, where she would be laid to rest. I was left with a Welsh doctoral student, Fyon, and a German Shepherd, Hannibal, that we had volunteered to take care of. As Fyon had classes, I was in essence mostly left alone to bond with the German Shepherd.

It also meant that I had to learn to travel in Copenhagen without Peter holding my hand. On Friday, just forty-eight hours after I had submitted my visa application (a far cry from the three weeks I had been told I needed), I went to pick up my passport at the Ukrainian Embassy.

And there on page nineteen was the Ukrainian visa, half written in Cyrillic script. It was then that I learnt that my name in Ukraine would be 3YKICBA YOHHEP. At least the mayor’s letter was no longer Greek to me.

I sent Nelly a message on Messenger: ‘Got visa. Will travel.’

She texted back with a thumbs up emoji. But curiosity was killing me, so I had to call her.

‘What did you say to that woman?’ I asked.

‘I asked her,’ Nelly told me, ‘whether she was stupid or something. I asked her whether it makes sense that someone who is in Denmark would leave it so they come to Ukraine to stay. I added,’ said my crazy and smart friend Nelly, ‘Her passport is South African. People from Ukraine are trying to leave and stay in South Africa, not the other way round.’ And, just for emphasis, she asked her again, ‘Are you stupid or something?’

It sounded like a very risky move, but I was glad it had worked.