How streaked we are by what we see: Teju Cole is at his engrossing best in his new book, Blind Spot, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

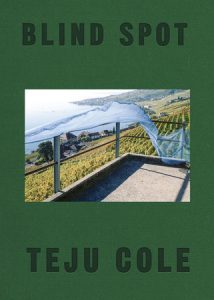

Blind Spot

Teju Cole

Faber & Faber, 2017

There was a time, not three or four years ago, when Teju Cole was everywhere. He seemed to spring from the internet, fully formed and precocious, and possessed of trendy buzz. The noisy reception that greeted Cole’s novel Open City shone more light on a figure who had been quietly writing and thinking about the world for a long time. That hot flash of cultural awareness is somehow at odds with Cole’s temperament, though he has been at times a prolific user of social media. When I heard he would be in town for a literary festival three or four years ago, I spent the week stalking the city looking for the face from that iconic photo in which he is framed by his peaked cap. In person, Cole was quiet, serious in manner, sharply drawn and yet inscrutable. I recall being surprised at his lack of hair; ‘Teju Cole’ was for me a faintly unreal image appended to a work of thought.

A work of thought is certainly what his latest work, Blind Spot, happens to be. At a time when the photograph has been simultaneously elevated and banalised by Instagram, Cole’s decision to publish a collection of images seems initially odd. Where is the next novel? But Blind Spot is more than just a selection to be disregarded on a coffee-table: while it rewards dipping into at random, it is a work of quiet intensity that simultaneously testifies to Cole’s impatience with traditional novel-writing.

A work of thought is certainly what his latest work, Blind Spot, happens to be. At a time when the photograph has been simultaneously elevated and banalised by Instagram, Cole’s decision to publish a collection of images seems initially odd. Where is the next novel? But Blind Spot is more than just a selection to be disregarded on a coffee-table: while it rewards dipping into at random, it is a work of quiet intensity that simultaneously testifies to Cole’s impatience with traditional novel-writing.

I suspect that it is this impatience that might account for some of the scepticism I’ve heard directed towards his work. Cole is one of the great modern writers of abstraction, and he sees the world through a summarising eye. To some, he comes across as being deliberately deliberate, wielding a disciplined assuredness of opinion on matters of art and literature that casts him among people like Henry James and Susan Sontag, but that also makes him sound like he’s lecturing you. When he’s on song, this can be wonderful, as many of the gemlike essays in his Known and Strange Things demonstrate. But quite a number of those same essays have a cruise-control ease that whiffs of a writer for whom the strange things are not altogether strange: the smudge of research is not always thoroughly removed from these long pieces, as though Cole is uncertain that his writing is enough to bear him across the material.

Nevertheless, Cole is a writer whose curiosity drives him to move through the world noticing things. His materials are paintings, music, books and films, objects that generate ideas whose branchings Cole describes in concentrated prose. In his stories, characters excogitate, but the reader’s eye is drawn to their movement and their stillness and the way they engage with streets and people and houses and trees. In the long format required of essays, this can be a tad overpowering: pleasure becomes prolix once too often in Known and Strange Things, like a dessert of excessive density.

But Cole is at his engrossing best in a work like Blind Spot, when he is poring over small things, turning them this way and that to reveal the poetry within. This should come as no surprise, given that his most interesting (and therefore successful) experiments with form take place on (in? using?) Twitter and Instagram. Cole’s specialisation is in backdating modern forms of communication, so that tweets and shouty newspaper headlines connect to Flaubert and Gide and Barthes in ways you might not expect.

Blind Spot is a vividly fertile book, running to some 320 pages. Each photo is accompanied by a faceted jewel of diaristic ideas—the photos are Cole’s own, and the book is in some ways a travelogue, a record of having been in Tivoli or Queens or São Paulo, of having passed through those spaces while thinking things. The author looks at his photos with an estranged eye, noting a detail here or a flutter of colour there in a proliferation of succinct entries which coalesce around ways of seeing.

Cole makes healthy use of influences like WG Sebald and (especially) John Berger: the photos are not simply described, they are catalytic occasions for exploring memory. From each page springs a nimbly digressive essay that proceeds via allusive cadence rather than the compacting force of declarations. Dreams, fragments of novels and stories in various forms all weave together to provide—what exactly? Backdrop? Counterpoint? If anything, they disrupt the solipsism of personal photos not by rendering the images transparent, but by overlaying them with meaning.

Running through these fragments, appearing in some places and disappearing from view in others, is Cole’s experience of tearing his retina, and the subsequent altering of his vision (‘I remember the pain when the doctor cauterised the holes in the retina of my left eye with a laser.’). This moment, which forms the epilogue of Known and Strange Things, here becomes a leitmotif for the problem of seeing. Like Breughel’s ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’, what the eye is drawn to is also a story of what the eye has missed. As Cole observes, ‘to look is to see only a fraction of what one is looking at. Even in the most vigilant eye, there is a Blind Spot. What is missing?’

This book is an encounter with the porousness of images. In Syracuse, Cole has a pareidolic moment, and looking at the image I see the face too, though I can’t recall if I looked at the picture first or if the meaning visited itself upon the image after I read the facing paragraph. This is an experience repeated often throughout Blind Spot: we reach for anything to tether us to meaning, but Cole’s words swing us further away from the safety of certainty.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.