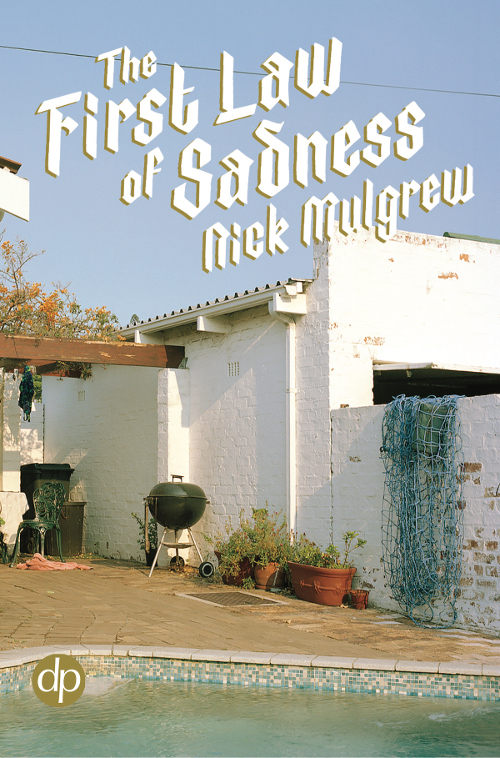

Exclusive to The JRB, new short fiction by South African writer Nick Mulgrew, excerpted from his forthcoming collection The First Law of Sadness, out from David Philip Publishers in September.

Smaller

Smaller

Nick Mulgrew

I

It had seemed to happen in past tense. Like a documentary, the patio door the bounds of some big-screen TV.

Cathy had been barely awake enough to notice the sudden interruption of the dog’s morning yaps, focusing instead on the softness of the couch, the warming of her hands on the first mug of tea, her attempts to ignore East Coast, snooze-activated on the bedroom clock radio. When she looked out at the dog, though, she only saw a war bonnet. A heft of feathers, bowed over, shadowing a foreign, kicking thing. It took a moment to realise what it was that the giant bird was pincering and piercing. She froze, holding her mug like a small trophy, the hot ceramic burning the skin of her palm.

Pinned on its side, the dog continued to kick. But after a moment, the bird tightened its grip, and then straightened its back. Finally she could see the bird’s small head, and hanging from its beak, a long strand of almost-brown flesh. The bird then turned, as if to face her, and flicked its neck back. Just as if it were taking a shot of whiskey, and acting about as satisfied afterward. The dog stopped kicking.

This was a bad start to the week, she felt.

And now, worse. The shrill shrieking of the neighbour lady, camel-toed into a pair of off-white linen pyjamas, speeding out into her back garden, adjacent to Cathy’s. Cellphone in one hand, she and her berserk purebred Pekingese rushed to the chicken-mesh that separated the gardens. ‘Shoo!’ she yelped. ‘Shoo, you horrid thing!’ Cathy would also have shouted then, if she had known her neighbour’s name, to tell her to move herself and her own mophead dog to safety. Instead, she watched the Pekingese yap, bare its overshot jaw of teeth, yap again. The neighbour lady bent to pick up sand clots from her flowerbed, throwing them underhand at the bird, which remained unmoved, needling around the dog’s face, seeking soft tissue.

The neighbour spotted Cathy watching from behind the sliding door. ‘What are you doing, for God’s sake?’ she screamed, waving dirt-stained hands. ‘Save your dog!’ But the dog couldn’t be saved, Cathy knew. The bird now flapped its wings, as if it might carry the dog off, but instead stepped back lightly onto the dew-soft grass, gave a once-over with a cocked head, and with mighty force took off, over the metal palisade and electric fence, and into the cobalt morning from which it had emerged. With the retreat of the bird went the neighbour, her nasal Midlands voice wavering in iambs, in time with her tottering steps: ‘Pe-ter! Pe-ter! You won’t be-lieve what hap-pened!’

In all, the production of bird, neighbour and dog had lasted only long enough for Cathy’s tea to cool. Her hands still clung to the mug, but sipping from it failed to soothe the lump in her throat. She put it down, opened the patio door.

Out in the open, there were two lives. So, she thought, approaching it, this awful dog was not made of wire after all. Its flesh was plumper than biltong. Here was red muscle, claret sinew, flesh still rich with the ichor of a small, strong heart. She bent over, put her hand to the dog’s belly—virgin skin, slightly sun-warmed. Up close, she could hear it making noises, a stillborn whimper, obstructed by liquid in its larynx. She moved her hand from its stomach to its spine, running fingers along a bony ridge, finding small, deep slashes in triplicate. Expert wounds, mirrored on each hemisphere of the body. It had never been the most aware dog. Maybe that was why this had happened.

She would have called the dog by its name, but whatever spirit that name signified wasn’t there anymore. Instead, something stiffening on a winter-brown patch of earth, in the loud winter sun.

There was only one life out there, now, in the open. A life too much for one body.

II

For breakfast, Cathy microwaved a readymade lasagna. Take your effortless pleasures while you can, she reckoned. She’d gone to work after the dog had died the previous morning, a pink beach towel shrouding the corpse. On her return, the body had been disappeared, a note posted to her gate, scrawled on the back of an airtime receipt. ‘I bury your dog’. For once, the body corporate’s gardener had shown some initiative.

‘All about new experiences,’ she said to herself on the couch, spooning the last dregs of béchamel out the steam-warped plastic tray. ‘All about new experiences.’

This was all new to her. Her present life was mostly a succession of things new to her. It was new to be a work-hermit in a complex unit. It was new to live in a house adjacent to a hectare of veld, with an electric fence to keep out potential intruders, which she assumed would all be land-based, if not reliably human. It hadn’t been new for her to look after a dog, but this hadn’t been her dog, not really. It had belonged to Amil, her husband, her ex-husband—whichever one he identified himself as at the moment. It had flip-flopped back and forth in the last six months, but mostly Cathy thought of him primarily as Amil as her emergency contact, the man with her spare set of keys. Theirs wasn’t a relationship that had crashed, but that was only because it had never taken off in the first place. No crushing disappointment, only yearning. Something more dreadful and unshifting; something that lurked more in the diaphragm than the heart.

Amil had walked out on his hometown as well as his marriage. He’d moved to Pretoria, trading one small, jacaranda-plagued capital for another. Pietermaritzburg had too many Hyundai mechanics for him to find enough work, he had said. He might as well have told her, ‘Pietermaritzburg had too much you.’

He had said it would be unfair on the dog to take it with him when he left. Even though it was objectively better news for the dog—she had paper-trained it, she had it taken to be neutered—she’d come to begrudge its presence. She supposed she needed to tell Amil about what had happened, but what to say to someone you had nothing to say to, about something you didn’t want to talk about?

The only person she’d told about the dog was the call-centre worker at the insurance broker. This in itself was a prelude to insanity. She should have known that life insurance for a dog was a scam, especially as an upsell to household insurance. Still, she had fallen for the pitch—’the emotional burden is softened by the financial boost’, etc.—at only an extra thirty-four rand a year. Now she was paying in other ways. The call-centre man had asked her for a receipt for the dog, which presumably she kept in the third drawer in her kitchen—that place everyone has for implacable miscellany—with the instruction manuals, the spent double-A batteries, the keys for unknown gates. He then asked for a letter from a veterinarian, as if dogs were important enough for death certificates. Remembering the neighbour lady and her cellphone, Cathy said she might be able to offer them pictures of the incident. They didn’t accept pictures, the call-centre man sniffed: they could be faked.

In lieu of an invoice or death certificate, the man told her to expect a visit from an adjuster from the brokerage to investigate the incident. She was also asked to prepare some sort of proof of ownership. But how are you supposed to prove the existence of something that is now literally dead, buried? All she had was snapshots, memories. And, apparently, memories weren’t facts.

These were the only facts. There was a dog. At six forty-five (ish) on the morning of the tenth of August, that dog was attacked and killed by an eagle. A crowned eagle, Stephanoaetus coronatus, to give it its proper name. Taxonomical knowledge thanks to a front page deep-cap in that day’s Witness, which had arrived courtesy of Amil’s standing subscription. It turned out that the neighbour lady had indeed taken pictures: she’d sent them to the paper. Cathy hadn’t exactly loved the dog, but this image was an indignity: the dog struggling on its side, while the bird showed off its great, pixellated backside.

Even so, she thought, this might be useful for her purposes. Here was her story, verified by an independent source. Except that the paper hadn’t identified her as the dog’s owner. It only provided the neighbour lady’s name: Cathy. Cathy Marais-Bushnell, as sodden a name as she’d ever read.

The adjuster was a small man with a polite beard and a gold tooth. His name was Giuseppe, like a cartoon character. He wore suit pants with a K-Way fleece, a clipboard and pen tucked snug under his armpit. The mountaineer accountant. He didn’t shake her hand when he arrived. ‘So this is your house, Miss Reddy?’ he asked instead, skipping any pleasantry, observing the modest, un-sheared topiaries outside her front door as if they were part of a movie set.

‘Mrs Reddy,’ Cathy corrected him. ‘And yes, this is my house.’

He walked ahead of her, through the open front door and into the lounge. ‘And what do you do to afford this house?’

‘Well, I was self-employed.’

‘Doing what?’

‘Accounts. But now I work at a school.’

‘Teachers don’t make much nowadays,’ he said, looking around the room, at her possessions. Cathy was taken aback by this line of questioning, as though someone might borrow a house to commit small-scale fraud. For the first time, she realised how few personal touches the house had. No souvenirs in the TV cabinet. No framed collage above the couch.

‘I do accounts there now,’ she clarified. ‘Actually.’

‘Uh-huh.’ Giuseppe raised his eyebrows, tapped his pen on his clipboard. ‘Can I see where the incident involving the dog happened?’

‘The back garden?’

‘If that’s where it happened.’

‘That it did.’ She unlocked the patio door and slid it open. Giuseppe eeled through the gap as soon as it was large enough to accommodate him. He strode out into the centre of the yard, as if to be in place before Cathy attempted any sleights-of-hand or horticulture. ‘So,’ he asked, pen poised above paper. ‘Show me where this incident occurred, please.’

‘Actually, you’re standing right where it happened,’ Cathy said. Giuseppe recoiled and looked at his feet. He looked disappointed at the lack of blood on the grass.

‘And where did this—this eagle come from?’ Giuseppe asked.

Cathy shrugged. ‘The sky?’

Giuseppe duly cast his gaze upward, then over the veld. ‘I don’t see any eagles up there,’ he said.

‘I understand eagles are quite rare.’

‘I’m sure they are. So, now where’s the dog?’

‘It’s dead,’ Cathy said. ‘Obviously.’

‘I mean, where is the body?’

‘Buried.’

‘Where specifically?’ Giuseppe looked around the garden as he asked. Cathy assumed he was looking for a patch of fresh earth. A small tombstone, too. In memoriam: doggy.

‘I don’t know exactly,’ she said, scratching her arm through her knitted jersey. ‘I think the gardener buried him yesterday.’

‘I’m going to need to see it,’ Giuseppe said, marking something down on his clipboard. ‘To cross-reference.’ They stared at each other a moment before Cathy, not knowing what else to do, decided to fetch the gardener. He would most likely be round the front, checking on the dagga seedlings he hid in the communal bushes. In the meantime Giuseppe stood outside, looking at the sky, holding hand to forehead, the world’s least likely twitcher.

A minute later, Cathy returned with the gardener, who smelt of tobacco and fertiliser, carrying his spade like a walking stick. Giuseppe clicked his pen and hovered it above his clipboard. ‘What’s your name, sir?’

‘Michael,’ the gardener answered.

‘And your surname?’

‘Michael.’

‘No, your surname.’

‘Michael.’

‘Michael … Michael?’

Michael stared back, nodded.

‘Come on,’ Giuseppe sighed. ‘What’s your real name?’

‘Michael.’

‘No, I mean …’ Giuseppe scratched at his brow with the bitten back-end of his pen. ‘You know … your African name.’

‘Michael,’ Michael said again, serene as a cherub.

Giuseppe turned to Cathy. ‘Your gardener isn’t very forthcoming with information.’ Cathy shrugged. ‘He’s not my gardener. He’s employed by the body corporate.’ Everyone’s responsibility, therefore no one’s.

Undefeated, Giuseppe turned back to Michael. ‘Did you bury a dog yesterday?’ Michael nodded. ‘Can you please take me to where you buried it?’ Michael nodded again, and duly led the three of them through Cathy’s side gate, around the front of the house onto the grass in front of Other Cathy’s house, and pointed to a rectangle of recently-turned earth.

‘Why would you bury the dog here?’ Cathy asked Michael.

‘Miss Cathy asked me to bury it.’

‘No, I didn’t,’ she said, before realising he meant Other Cathy. ‘No, wait. No—you must know it’s my dog.’

‘But Miss Cathy asked me to bury it,’ Michael protested.

‘But you took it out of my garden.’

‘But she asked me, madam.’

Giuseppe looked at the patch of soil and then at Cathy. He smiled for the first time, the gambler spotting the ace up the dealer’s sleeve. ‘So how do I know it’s your dog buried here, Miss Reddy?’

‘Mrs.’ Cathy looked at the small grave, as much to avoid Giuseppe’s gaze as to rack her brain. Surely Other Cathy couldn’t be happy about her garden being torn up for a stranger’s dog? Would serve her right for meddling. Finally she remembered something: ‘He has a collar. It has my name and address on it.’

‘Where is the collar?’ Giuseppe asked.

Cathy pointed at the grave. ‘Guess it’s in there,’ she said, and looked at Michael to confirm. Instead, as if on cue, Michael took up his spade and started digging, gumbooting the blade into the earth with a metallic scrape. Light-stomached, Cathy turned and looked instead at her own small front garden, with its shaggy grass and limp daisies. Why did Michael never tend to it like he did Other Cathy’s? Michael swiftly uncovered the dog’s torso and, holding his nose against the tang of rot, unbuckled the small white collar, already crusted brown with earth. ‘Here, boss,’ he said, offering it to Giuseppe, who pinched the fabric gingerly in his fingers, and examined the small bronze amulet that dangled from it. He began to laugh.

‘I’m afraid this solves nothing, Miss Reddy.’ He placed the collar in the centre of her palm in a way that was far too intimate for her liking. She turned the medallion over. On one side, it had the dog’s name: HUNTER. She flipped it over to where she’d had her details engraved by a woman at the Midlands Mall. She realised she should have splurged on a bigger amulet:

OWNER: CATHY

ASSEGAI MEWS, BESTER

RD, HAYFIELDS

‘Shit,’ she said, and Michael began to rebury what was exposed of the dog. Cathy thought of asking him to stop, of asking him to exhume the entire corpse, so that she could prove her ownership of the dog by her intimate knowledge of all its grazes and scars. Or she could ask Other Cathy to confirm. Where was the woman, the one time her presence was actually wanted?

‘I’m afraid this doesn’t help your claim, Miss Reddy,’ Giuseppe said.

Cathy felt something inside her snap like a dowel. ‘Look here,’ she said. ‘Of course it could have been any dog we have just exhumed, but the fact is that right now I do not have a dog when I used to have a dog, and there are a dozen fucking peop—’

‘There’s no need to—’

‘—including Michael Michael here, and my ex-husband, who can fucking attest to—’

‘Miss Reddy—’

‘For the last fucking time’—Cathy took a step closer to Giuseppe, her nostrils flaring, as much in response to his liberal use of aftershave as much as her indignation—’it’s Mrs. Mis-sus.’

Giuseppe stood back. ‘Mrs Reddy, you’re going to have to calm down, or I’m going to leave.’

‘No,’ she said, flapping her hand, ‘I’m leaving.’ She turned her back on the adjustor and walked over to Michael, who was three spadesful away from reburying the dog. She threw the collar back down into the shallow grave with all of her force. Thinking her grand gesture a mistake, Michael bent down to fish out the collar back out again.

‘Leave it!’ Cathy snapped.

‘Yes, madam.’

‘And why don’t you ever trim my hedge?’

‘Yes, madam.’

It occurred to her that she should be thanking Michael. Instead she walked back inside her house, shrieking the patio door closed behind her, leaving the two men outside, spaded, clipboarded, to consider each other.

III

Nobody visited. Nobody called. Not Giuseppe. Not Michael, although the hedges had been trimmed. And certainly not Amil. Strange how she pined for his presence now, to hear the familiar whine of his old Atos in the driveway, to listen for his woodpecker-ish knock at the door. To smell his shirts, the waft of drained oil masked by cologne.

Only mail arrived; the newspaper, electronic missives from the insurance brokers. Their first correspondence contained a certain poetry, a corporate litheness borne out of a blue-carpeted cubicle in Scottsville: ‘The senior process consultant who was appointed to complete the administration is still in the process of completing the administration.’ Two days later, the verdict came: ‘In our opinion,’ another nameless worker wrote, ‘there is some doubt that the dog in the incident was actually yours.’ Our opinion? She tried to call Giuseppe, to argue, to appeal, but the number on his card went to a call centre.

Everyone’s responsibility, therefore no one’s.

- set of cutlery, cheap (Checkers?)

- kennel, bowls, Kongs, etc.

- 32 books, mostly autobiographies, Formula 1

- two years’ issues of FHM

Cathy had taken out a new policy. Her uncle was a small-scale broker in Estcourt, who mostly looked after factory farms and small textile businesses. They’d never been particularly close, but she knew him well enough to know he wasn’t as obsessed with epistemology as her now-previous brokers.

The first step, he said, was to complete a full survey of her household possessions, nothing spared. General insurance was generally bad.

- braai tongs, 4x

- flip-flops, one pair, bottle openers in the soles

- case of red wine, blended

- paintings of landscapes, various

Stock-take, she reckoned, would be a weekend’s work. She had no conception of the contents of her home in their entirety. Everything had been moved in wholesale by the van lines.

- Noritake dinnerware, full set (except for side plates)

- guitar amplifier

- bonsai shears, trowel, etc.

Apart from the big tickets—the Coricraft couch, the large appliances—it was a catalogue of the quotidian, the forgotten, the things in the back of cupboards. But the job turned out to be surprisingly quick. While it had felt as if the detritus from her old life was everywhere, it was minimal in physical presence. Photo albums and VHSes didn’t have to be flipped through and counted—they couldn’t be insured, anyway. Whatever Amil left behind and wasn’t useful was cairned together, to give to Michael Michael the next time she saw him. He probably didn’t have any use for rugby annuals, but maybe he could get something for them from a second-hand shop.

Last was the garage, which she assumed contained only her Charade and some old paint tins, speckled with of the palette of the complex buildings—stone, peach, terracotta. But from the closets came a jumble of sporting equipment, shoved into place by a removal crew anxious to clock off. A tangle of ropes, strings and packets, shuttlecocks and rugby balls caught and wrapped like flies in a web. She yanked it all out in a single heap. As she was about to pick it up and add it to the Michael Michael pile, she saw something else: a rogue duffel bag, familiar in its bright pink colour, its synthetic fabric. She hauled it out, unzipped it, and breathed in a forgotten scent. Inside was Amil’s paintball gear. Gloves, sweat-stained chest pads, small plastic bags filled with yellow-and-green paint marbles. That oil-scent: heart-stopping. She rummaged, pulled out an old T-shirt, scrunched it up to her nose, inhaled.

There was something else in there, too. Surely he would have taken this with him—but apparently not: several thousand rands’ worth of paintball gun. Just like she had been, it was once Amil’s favourite. She picked it up, heard the weighty rumble of paintballs in its hopper, measured its too-realistic weight. She had always loathed guns, mystified by Amil’s love of carrying imitations of them into the identikit post-industrial warehouses that constituted most paintball arenas. Rotating it, her finger curled itself into a catch, and the gun jumped out of her hands. It fired, its mighty kick-back echoed by its dropping onto the concrete floor. Cathy recoiled, shrieked, and stared at the sudden colour on the wall next to the cupboard. Fluorescent green running down the white plaster.

Immediately she understood. She picked up the gun, braced it against her shoulder, and laughed in time with its rapport.

IV

Pepper steak pie, diet Sprite. Breakfast. She unfolded the newspaper, and saw it. The second headline: DOG OWNERS: DON’T PANIC. Cathy shovelled microwaved pie into her mouth, her jaw clicking metronomically as she chewed, and read. ‘Local experts say dog owners need not be concerned, after a picture of a dog being killed by an eagle in Hayfields earlier this week went viral.’ It would be typical, she thought, if they mentioned it was her dog after the hassle with the insurers. But like most papers, they profiled perpetrator, not victim. They interviewed someone who owned a rescue for endangered birds of prey in the central Berg. It was uncommon, he said, for crowned eagles to venture so far away from their nesting areas, but habitat destruction was forcing them to hunt further afield. ‘Even though this was unusual behaviour,’ the man warned, ‘there’s no predicting what a desperate bird will do.’ Cathy hummed her approval through the last bite of her pie—she could relate.

A strange idea had visited her while she was cleaning the paint off the garage wall. Cathy was the kind of woman who would wait a few days before doing something. If her enthusiasm dissipated, it was a sign that she shouldn’t buy that sundress, watch that film. Maybe this was why she only left the house to go to work. But this was an idea that wouldn’t leave. And that meant she needed to practice.

The gun waited on the coffee table. The morning was cool through the patio door, and the veld beyond her garden glistened with the same glow as the brushed metal of the palisade fence that separated her from it. The rustle of tall grass and unseen insects within. This could be her private arena: shades of Isandlwana. She walked up to the palisade, and aimed the gun through its gaps, searching for a target. There was little that was solid out there beyond a bank of acacias. Braced against bone, the gun made a comforting thud, like a nail driving into masonry, a point forced and made fast. The balls shot from the barrel and, curving slightly downward, made their mark: a sequence of magenta and green and yellow, spattered on brown bark. Some missed, hissed through the grass, catalysed the jumping of crickets. The rifle fired an automatic procession, the heartbeat of bullets followed by a fizz, compressed air and dull plastic, a bucking becoming more pneumatic with each shot, until the birds hidden in the veld—the finches and white-eyes and the swallows—began to stir. She followed them in her sight, turning as they flew over her head, disappearing over the roof of her unit with small calls and flutters. She refrained from shooting at them, mostly because she didn’t feel like scrubbing more walls.

The fresh silence that followed was cut like a sawblade on metal. ‘What on earth do you think you’re do-ing?’ Other Cathy appeared in the same linen pyjamas as the other day. ‘I saw the whole thing, you bloody girl. Who do you think you are, shooting at those precious trees? Look what you’ve done! It’s a-tro-cious!’

Cathy turned toward Other Cathy, who’d waddled over to the chicken-mesh fence. ‘It’s just paint,’ she shrugged. ‘It’ll wash off next time it rains.’

‘I have a good mind to report you for vandalism. I mean, just look at the state of those beautiful trees.’ Cathy turned and looked at the trees. ‘I quite like it,’ she said, and meant it.

‘What person in their right mind would think that? You’re like the rest of them, doing bloody graffiti on the walls in town. This used to be such a beautiful city, and now you can’t drive through town because of you people.’

‘Calm down,’ Cathy said. ‘Seriously, it will wash off.’

‘That doesn’t matter.’ Other Cathy had stopped shouting, dropping her voice an octave, like an angry headmistress. ‘I know what kind of person you are, girlie.’

‘And what kind of person is that?’

‘A careless person. I’m actually happy your dog died.’

Cathy could feel her smirk collapse.

‘You obviously you have no respect for animals,’ Other Cathy continued. ‘You’re not fit to own a precious little animal. You left him alone, outside, vulnerable.’

‘That could have just as easily been your dog.’

Other Cathy laughed, her voice returned to its usual high pitch. ‘No it wouldn’t, because my little one is trained. Plus, I am vigilant. I’m not some slob who lives al—what are you doing?’

Cathy had reset the gun in her hands, and slowly and deliberately raised the barrel at Other Cathy.

‘What on earth do you think you’re doing?’ Other Cathy took a step back, raising her hands. Cathy in turn took a step toward the chicken-mesh, now bringing the sight to her eye. This was purely for effect—Other Cathy was a much easier mark than the acacias.

‘You revolting bitch,’ spat Other Cathy. ‘I’m going to report you right this minute!’ Cathy continued to advance to the chicken-mesh until the Other Cathy was close enough to her patio door to bolt inside. The click of a sliding door. A shuffle of keys. Cathy could hear the Pekingese yap from inside her neighbour’s house, scared at the now-shouting voice of its owner. Heading back inside, and putting the gun down on its coffee-table spot next to the newspaper, Cathy didn’t bother locking the door behind her.

V

Getting up at four was worth it: no one else was at Monk’s Cowl. Or so she thought. In the pre-dawn gloom she hadn’t seen the young ranger in the shed, who called out as she pushed through the hiker’s gate. Sure her plan was over before it had begun, she trudged over to the shed, certain her bag would be searched. But through the open window, the young man only pushed a form on a clipboard. ‘Please fill out, madam.’

Name, address, date of birth. ‘What’s this for?’ Cathy asked.

‘So we can search for you if you’re not back by sunset,’ the guard said, his breath visible even inside the relative warmth of the shed. The we was most probably royal: the ranger looked like he hadn’t seen anyone in days. From where she was standing, the inside of the shed looked bare, save for a pile of fold-up maps, a small paraffin heater, a battery-operated radio playing white noise mixed with a touch of gospel. ‘We can’t let people go missing in this cold,’ the guard added, rubbing his nose on his jacket sleeve.

Worried the information might be used against her, Cathy transposed a few letters and digits. Clipboard returned, the window slammed shut, the static on the radio turned louder. Warmth more important than security.

Cathy studied her surrounds. Maybe someone else was hidden in the half-light. To her left was the car park, empty save for her Daihatsu and a couple of Jeeps in the overnight stay, and the visitors’ centre, encircled by locked stalls stocked with curios—hand-branded walking sticks, factory-carved animals. To her right was the main path toward Cathkin Peak, which she took. Both sides empty of human life—but still she felt watched. She read the previous night that the closest look-out point over the mountains was at Sterkspruit Falls, a twenty-minute hike. It was the vantage people visited most, but at six in the morning in the off-season she reckoned she’d be the only person there. It was only once she was on the main trail, cleared its long, arching tunnel of evergreens, that her chest loosened and she could breathe. Finally, space. The misted vista, flecked with trees and winter shades—orange, cobalt, charcoal, purples like fading bougainvillea. Grass gorse and goldenrod, glorious, wind-parched. The shrubs along the path were bloomless, the ferns silvered and curled into chameleon tails. Over some distant hill, she could see thin trails of smoke rising. Small combustions in the bronze veld, edging along firebreaks, coerced into life outside rondawels.

The path she followed was well-graded, beaten by heavy men in heavy boots over heavy summers. It rose in soft curves, signposted by stones hand-engraved in roman, winding toward the falls, visible even from here as a great sheet of rock. Walking in the rising sunlight she was at once too cold and too hot; her legs not yet warm, her lungs not yet elasticated. She distracted herself with the crunch and slide of her shoes on the russet gravel, the appearance of distant horses, mottled white and black, dirty like dishtowels. The path levelled, and a dense flourishing greenness rose to meet her. Trudging, the strap of Amil’s duffel chafe-kissing the side of her neck, she strode more forcefully toward the ridge. Sooner than she expected, the falls revealed themselves to her: a not-inconsiderable gushing from the rocks a hundred metres on the opposite side of a small valley. All around was green, fed by the vapour rising like smoke from the water’s landing below.

It took a knee-cracking descent to the lookout proper—a concrete slab, two metres by three, with a guardrail and a bench, which had been decorated with a small gold plaque. In memoriam: Granny. It was damper than she expected down here, spiced with algae and the verdant dew-bush awakening. She dropped the bag, and loosened her shoulders. In it was only her purse, and the reloaded rifle. Taking it out, she realised how ridiculous it looked in her small, avian hands, how ridiculous the lurid pink bag was among all these things around her—things that were so enthusiastically un-human. Sight to eye, she cast her gaze over all the small spaces in the great vault of air before her. But no birds flew, no calls soared over the rush of falling freshwater, melted snow from the amphitheatre of summits above her. Life, she reasoned, needed to be coaxed out. She took one shot into the expanse. As before, the kickback and its echo much stronger than she imagined. She scanned the sky again, and the bushes encrusting the cliff below her feet. She checked her watch. Six, the waking hour, dead. Bracing herself better this time, she fired another round into the air. The echoing of nothing.

There was supposed to be a narrative to this, should imagination and reality have intertwined: she would come here, where the paper said a crowned eagle might be, and she would find it, and she would shoot it with her estranged husband’s paintball gun. The idea seemed perfectly reasonable in her head, but standing here, looking for a bird with a non-lethal gun in her hands, it disintegrated. That was the problem with reading reason or purpose into things: those things didn’t exist in her life, overtaken instead by the delirium of the desperate, riding an ox-wagon deep into the province of vanity. Maybe, she thought, I should just pack it in—the gun, the search, everything.

But then—an interruption to the self-belittler. Stark against the cloud, a tiny silhouette riding a thermal above the falls, curving slowly heavenward. A speck, a floater skidding on eyeskin. There was no telling what it was—kite, crow, falcon, eagle. Training her sight, she prayed it would find vermin in the cracks in the rocks by the falls, reverse its altitude. Shoulders re-tensed, seconds passed, then a minute, as the bird continued to ascend. From someplace nearby came the sound of hooves on gravel, but she refused to turn around. She peered, unblinking, through the small plastic sight, the bird lazily twisting within its borders. Come on, come on. Dive. An incantation. Dive.

More hooves.

Dive.

An intersession heard. A corkscrew rotation, and the bird fell, terminal, toward the falls. Towards her. She followed it with the barrel, her finger lubricating the cheap plastic of the trigger with sweat. She had no idea something could fall so fast. As it closed down on her, she could see it more clearly: the striated brown and beige, a feather-horned head, seven pinion spikes. It was the bird, she thought. The bird, with its doric legs and wings four feet across. And in her eyes it was coming for her, this killing thing. She imagined herself in its gaze, in its yellow eyes; how small she must seem from where it was. And growing smaller within herself, even as she grew in its sight.

She fired. Her hand spasmed into a claw, the paintballs rushing, a gatling whine overpowering the gargle of the water below. The bird deviated from its path towards her, and twisted instead toward the opposite side of the ravine. She fired four more shots, attempting to intercept it. The balls missed, zipping and curling downwards, landing in Fizzer-pink splotches on the rocks below. A crime of colour, among the khakis and the olives and the emeralds.

The bird made one last turn before it fanned its chestnut tail in airbrake—presenting to Cathy the view in which she had first seen it standing over her dog—and then enveloping itself in the bush with a vegetal crunch. She kept her barrel trained on the bush into which the bird disappeared, although she knew it was now out of range. Knowledge of this created a tremor in her, starting slowly, but soon juddering within her bones and in her marrow. And for the first time in months, she began to cry. Not like the falls, not hysterical, nor sobbing, nor heaving. Just a soft leak. A tap, an ancillary connection inside her that had come finally loose.

She didn’t bother putting the gun back in the bag, dropping it where she stood, a few paintballs still rumbling in its hopper. She collapsed, hunched on the bench, and cradled her head in her palms. The hooves of the horses sounded closer. She immediately recognised the cold-constricted throat of the young ranger. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘Miss Reddy?’

‘It’s Mrs.’

VI

On Monday the paper arrived as it always did. It had at last named her as the owner of the dog, but only in connection with her punishment. No charges pressed, only a fine and a ban from national parks, saving her from spending a Sunday in a holding cell. She didn’t have to call in sick to work—they’d been pro-active in putting her on paid leave. Of course, it was only now that people were calling to check up on her. She unplugged the house phone, set her cellphone on silent. From her bedroom she could hear a sympathetic snick of shears on hedge. In the veld, the acacia was still pocked with colour, and in the ground outside a neighbouring house, a dog still mouldered.

She stayed in bed, purgatoried in dreams of birds and grass, of falling from cliffs into a dark ocean. She woke from one of these visions to hear the phone vibrating incessantly; a stream of calls like a mosquito whine in the far corner of the room—something it was programmed to do in response to only one caller. Her mood was darker now, and warm. Warmer still when the phone ceased buzzing, a familiar hum in its place, hesitant in the driveway. A click, a slam.

She was on her feet by the time the knock came on the door.