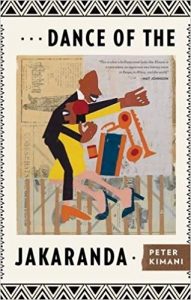

Dance of the Jakaranda

Peter Kimani

Akashic Books, 2017

Two Europeans exchange confidences on a train travelling through the Great Rift Valley. Following after them, in separate coaches, groups of Indians and Africans sing in celebration of the train’s maiden journey. The year is 1901. Sixty-two years later, a kiss in the dark sets off a search that ends, after many twists and turns, with the death of a young man. This is not a love story.

Two Europeans exchange confidences on a train travelling through the Great Rift Valley. Following after them, in separate coaches, groups of Indians and Africans sing in celebration of the train’s maiden journey. The year is 1901. Sixty-two years later, a kiss in the dark sets off a search that ends, after many twists and turns, with the death of a young man. This is not a love story.

There is more, of course. The kiss is, in fact, a collision that defies the certainties of a generation divided into neat, immutable categories, listed in order of descending privelege—White, Indian, African. The Jakaranda Hotel where the kiss happens, a nightclub in Nakuru in what is now Kenya, is a place for a last stand atop a hill, a place to wait for the fire to come.

At the centre of Dance of the Jakaranda, Peter Kimani’s third novel, is Rajan or ‘Raj’, a Kenyan nightclub singer of Indian descent, who, upon being kissed, becomes a majnoon, a madman on an absurd quest to uncover the identity of whoever kissed him. It takes all of thirty pages for the woman’s name to be revealed—Mariam—but it takes the duration of the novel for us to discover who she really is. When Raj and Mariam meet, on the eve of Kenyan independence in 1963, the train that initiated the story comes off its rails, and the lines of its track, meant to run along in parallel forever, like Kenya’s race groups, start to twist and converge.

Said initiation of the story begins with Ian Edward McDonald, a British civil servant and ex-military man tasked with overseeing the construction of a section of the East African railway from Kisumu, through Uganda, to the port of Mombasa. His task completed, he looks forward to retirement and a knighthood at least.

The second person on that first train ride is the Reverend Richard Turnbull, with whom McDonald shares a secret surrounding the birth of a child. McDonald can barely contain his distaste as they speak about an Indian worker from the Punjab, named Babu, who is thought to be the father. When pressed by McDonald to divulge the child’s ethnicity, Turnbull refuses, asking, ‘What does it matter? […] What’s done is done.’ It later emerges that Babu and McDonald have been locked in ‘a grudge that would last a lifetime’, originating in a worker’s protest that was sparked off by Babu’s clumsy but well-meaning attempt to translate between the newly-arrived Indian workers and their colonial masters.

When McDonald’s retirement plans are upended and he receives the title deed for a piece of land instead of a knighthood, he channels his energies, and the conscripted labour at his disposal, into trying to win back his estranged wife, Sally. He selects a picturesque site in Nakuru and there builds a palatial house as a monument to his love for her. But when Sally unexpectedly arrives to meet McDonald and observes the unmitigated brutality with which he treats his Africans workers, she rejects both house and master. This rejection ushers in a period of solitude and grief that lasts for four years. As the future unfolds, the house becomes by turns failed ranch, a hangout for the colonial flapper set, and the fated Jakaranda Hotel.

The last decade has seen an increase in quality African fiction that tackles issues of national history and interrogates where and how Africa and Africans fit into the global picture. Nowhere is the curious mix of peoples so diverse, and the potential for conflict as the fuel of memory so plentiful, as it is in East Africa. Dust, the debut novel of Kenyan writer Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, a contemporary of Kimani, is exemplary of this type of fiction, for its consideration of ‘what a nation does, or does not do, with its freedom’. Then there is Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, whose Kintu boldly approaches historical Uganda through the story of a Bugandan clan head, his descendants, and the unleashing of a transgenerational curse. Further afield, in central Africa, Fiston Mwanza Mujila has captured the angst of the Congo in Tram 83, a novel that follows two friends through an underworld of Marx, jazz, easy women and mineral prospectors. These books, like Kimani’s, locate a point in our past, place their finger on it, and seek to reimagine it, in the way only fiction can. In this, they hold up a blend of mirror and window to African reality, and venture an answer to the question ‘How did we get here?’

The story of modern Kenya is the story of railways. In 1896, the British, seeking to maximise the economic benefits of their East Africa Protectorate, set about building the railway featured in Kimani’s novel. This was accomplished with the labour of several thousand Indian workers, whose descendants form the Indian communities in both countries today. But the railway was built—and this is an important point—on land seized from Africans who had not exactly agreed to the terms of the situation. And today, the thorny issue of land rights underlies the region’s often tumultuous identity politics—from Kenya’s 2008 post-election violence, to Uganda’s ever-simmering geographical tensions, to Robert Mugabe’s expropriation of white farmer holdings in Zimbabwe. Although Dance of the Jakaranda takes as its setting the birth of a nation, it manages to facilitate a contemporary reading of the area in terms of today’s issues. When that first train chugs past, the Africans are amazed by the great ‘iron snake’ come to life on the tracks, but do not consolidate sight and sound, considering the rumbling to be merely another earth tremor. For, significantly, their Rift Valley has always been a place of paroxysms, a place in which certainties dissolve. When Rajan asks Mariam about her ethnicity, she replies, tellingly, ‘I have no tribe.’ And then, after a moment, ‘I have no family.’

The tale is told over four sections—’House of Music’, ‘House of Silence’, ‘House of Light’, ‘House of Darkness’—and a prologue, and Kimani makes use of a large cast and a cascade of events to keep things chugging along. The Indians, the Europeans and the Africans, each affected by the others’ mistakes, and guilty of the repression of crucial facts about their fraught shared past, are fated to collide—and with this collision comes transformation. We arrive at that stop in the novel that may be called its heart, where Rajan and Miriam and their generation suddenly inherit the past. A host of characters—including the comic butcher Gathenji, with his subversive stories, and Babu’s friend Ahmad, who takes a liberty with Fatima and fails to deliver an important message—serve as diverse entry points into the story, but they are all also there to point to the question of Mariam’s origins. And it is only in the final pages that we learn the truth.

So, to return to the matter of national narratives, are the Africans and their continent in Dance of the Jakaranda meant only and always to supply the background for the actions of others, whether these be the building of McDonald’s railway, or Rajan’s crooning, which captures the dreams and aspirations of a new generation? ‘What have we been?’ is the question, and, following it like a twin, ‘What are we now?’ Kimani’s novel answers these questions, like its narrator, in knowing tones and meta-fictional turns, which make the book a fine example of contemporary literary fiction. The fuel of memory in Kenya—violence—ignites; tragedy ensues; the destruction is instructive.

What Kimani shows us is that while it is true that there may be a focal point for every moment in history—the building of house or railway, or the construction of an identity—there is always more to it than that. History, like those Africans on the first page knew, is also about outbursts of energy, from which only the people go on: changed, transformed, sometimes seemingly destroyed, but always still there. It is in these outbursts that we locate modern Africa. The forest burns so that new shoots may grow, everything and everyone is mutable, the monuments become piles of ash and then rise again, in the eternal human trick of emphasis. The generations emerge, phoenix-like. And all of this, in a sense, is thus a love story too.

- Richard Ali is a Nigerian lawyer and novelist; his debut novel, City of Memories, was published in 2013. He is a member of the Nairobi-based writer’s collective Jalada Africa, and sits on the Board of the Babishai Niwe Poetry Foundation, Uganda. Follow him on Twitter.

Image: Yusuf Wachira

Index

Authors

- Fiston Mwanza Mujila

- Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

- Peter Kimani

- Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

Books

- Dance of the Jakaranda

- Dust

- Kintu

- Tram 83

Topics

- British East Africa

- Colonialism

- Indentured labour

- Kenyan independence

thanks to this great collumnist

I stopped with the first spoiler – the revelation of the woman’s name. A review must always know what to say and when to stop…