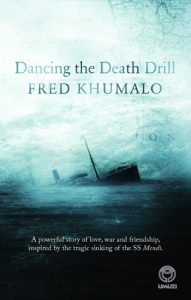

Dancing the Death Drill

Dancing the Death Drill

Fred Khumalo

Umuzi, 2017

The historical novel presents rough seas for a writer. Attaching a novel to a particular historical occurrence—particularly tragedy—means the author has to constantly negotiate an uneasy closeness. On the one hand, one has to guard against producing an ersatz textbook, staggering under the weight of historical facts, and generally being a bit of a bore. On the other hand, if one doesn’t compact an immense amount of the real into one’s fiction, one risks being accused of sloppiness.

A bad historical novel feels like watching an autopsy. The best of them (you’re thinking of Hilary Mantel, but there are others) employ a dazzling syncopation of improvisation and veracity: they ration the historical side and find what is interesting in the desiccated details, mining the hollows for their fiction. They don’t tell their stories in a teacherly voice, but rather invite the reader to sail on the wave of good narrative.

Such beguilement may be traced in Fred Khumalo’s new novel, Dancing the Death Drill. Using the real-life tragedy of the SS Mendi’s sinking in the English Channel in 1917 as a fulcrum, the story swings in a wide and expansive arc with a velocity that pulls the reader in from the first page. It’s a novel in which history’s brine trickles through the invented story. The Mendi’s sinking is an event that has only recently been brought back to prominence, and with that bringing back came the mythic account of the doomed Black soldiers resignedly and courageously going down with the stricken ship, under the leadership of Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha, who stood firm on the deck and exhorted:

Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do … Brothers, we are drilling the death drill.

Dyobha’s words have become the stuff of legend, but it is only some 200 pages into Khumalo’s novel before we read these words; and a further 150 before the story’s stark terminus. That the sinking of the troop carrier is not Dancing the Death Drill’s sole focus should not compromise its status as a work of truth-telling, however. The first part of the narrative begins, not in the grey twilight of the Great War, but in a Parisian riverside restaurant in 1958. The scene that follows puts one in mind of David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence, and is a breathtaking stairway into the novel. The main character, the enigmatic Jean-Jacques Henri, is whisked away to jail right at the end of the first chapter, leaving us to wonder how the novel will proceed.

Luckily, Khumalo’s preferred form of storytelling is the expository kind, in which a story is told to us by an interlocutor who delineates what must be told in vibrant and jazzy prose (a literary device not often glimpsed in South African fiction). The author grabs the painter and musician Gerard Sekoto from the historical scenery and drops him into the narrative. Thinly doppelgangered as one Jerry Moloto, he acts as coxswain for steering toward what has happened. Though the conceit wears thin in places, it’s an inventive detail whose believability seems beguilingly possible.

It also prompts the question of how to go about inhabiting historical otherness: how might voices be made to speak to us across time? How did people sound in 1917? What we know of twentieth-century Black life before 1945 is visual, the stuff of grainy grey images of men in quaint hats. Photos from those times look ghostly and uncanny because the exposures were so long that people had to stay more still and appear more composed than they do now. To give voice to these still images requires attentiveness of a particularly nuanced order.

Thankfully, Khumalo has honed his narrative gifts over the years: as a journalist, memoirist and experimenter with short-form stories, he has the gift of noticing and, more importantly, the gift of remembering. What he distills from historical record emerges with a clarity that is often thrilling. And yet Dancing the Death Drill does not seem gripped by the typical historical novel’s anxieties. It is a well-researched tome, but it does not seem particularly interested in drawing our attention to the scaffolding of history lurking behind the fiction.

What the novel is more concerned with is the question of what being different—that ugly scarring invented instrument that gave the pretext for the continent’s carving up—would have felt like to a Black body in the first half of the twentieth century. Jean-Jacques, or Pitso, to give him his original name—he is a self-created man of many names—is a servant of eventuality. He describes himself as ‘the product of these long-running wars of conquest’, being born after the Anglo-Boer War to a Basotho mother and Afrikaner father whose tragicomic relationship is ground up by the unfeeling racial politics of his home country, South Africa. Khumalo sets up this encounter between South African Blackness and South African Whiteness in their prototypical forms as a way to illustrate how the sordid tale of race relations that obtained in turn-of-the-century South Africa appeared, before it gathered into its even more insidious mid-to-late-twentieth-century mode.

A solitary soul, Pitso restlessly articulates a desire to control his own identity, at a time when such control was rapidly being wrested from people of colour:

If you ever call me a coloured person or a mixed-race person, I shall make you swallow your teeth. I am Pitso, the son of Motaung. The roaring cub of the Bataung people.

But after a while this changes, or seems to, and Pitso begins attracting the attention of those he encounters because he evades, rather than embraces, the all-too-narrow taxonomies by which identities are sorted. Is he Basotho? ‘Coloured’? French-Algerian? All of these, and none: for us, too, Pitso becomes an enigma, his interiority inaccessible—a pity, since characters whose opacity defeats even the reader can seem to be mere automatons carrying out the wishes of their creators. At a certain point in the novel, Pitso seems propelled less by anything discernible to the reader than by some inscrutable private motive. A child of tragedy, he is forever running from what the novel cruelly seems to suggest is an inescapable destiny: to be defined by history. In his smoothness he succeeds, for a while, in slipping history’s grasp—but it returns to lay claim to him.

When it comes to the interiority of friendship between Black men, on the other hand, Khumalo’s eye for detail is unfailing. In Pitso’s badinage with his fellow enlistees, the naïve Tlali and the flamboyantly violent Ngqavini, the novel captures the macho posturing and the shared grimace in the face of inequality with an attentiveness that inhabits rather than describes. But Khumalo’s ear for this ostensibly lost grain of South African speech occasionally loses its tuning, so that the men can sound stilted and formal in their pronouncements. Still, you feel the scenes as much as read them.

If Khumalo is obviously a talented storyteller, he is also one who seems occasionally impatient with his own medium. He favours straight narration over subtlety: His writing is placeless, except as he chooses to inflect it with the local. This means that some of the detail that lies folded between the conversations the characters have could be written by anyone at all. The story strains against the tools of its telling, and Khumalo’s superb colouration sometimes deserts his subjects. We are also served italics to convey authentic speech, a convention that should not apply to a novel as delightful and intriguing as this one.

That most of the book is rendered in superb prose makes the careless moments even stranger: A sex scene whose stylising is vexing—you can almost sense the author treading water to get back to the stuff he finds more interesting. Or this dismaying reportage on the moment of the ship’s sinking:

Drilling the death dance. Not crying, not panicking, not screaming at the approach of death. In Africa, even in times of death, people celebrate. Death becomes a spectacle, a moment of defiance, the defiance of death itself. Staring death in the face, challenging it to a duel. Come and get me, death. I am not afraid of you.

Who is responsible for this florid journalistic interpretation? Is it Moloto, telling a story that isn’t his? Is it Khumalo himself? If the former, then Moloto’s narration is more than unreliable, it’s downright questionable. If the latter, then the author’s proximity risks doing exactly what is described, turning death into a spectacle which occludes the tragedy whose banality—like Breughel’s ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’—is the real horror.

That would be unfortunate, of course, for the purpose of historical fiction is to allow us to approach the ordinary which has been sedimented over by time. What Dancing the Death Drill does is to take what is predictable—that which has already happened—and listen to it closely. In the oft-repeated words of the death drill, Khumalo ekes out a deeper truth.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.

wow! thank you for a wonderful review. I am humbled.