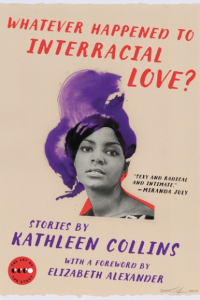

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?

Kathleen Collins

Granta 2017

Black women as you have never seen them before, on screen or on the page: as creative intellectuals, artists and activists, with complex relations between themselves and the world. In many ways the vision offered in the art of the late Kathleen Collins (1942-1988) is a window into her pioneering life as a civil rights activist, educator, playwright and film director, whose collection of previously-unpublished short stories, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, was released at the end of 2016.

The release of Collins’ 1982 comedic drama Losing Ground, one of the first fictional features by an African-American woman filmmaker—which was never publicly screened in Collins’ lifetime—at a 2015 film festival at the Lincoln Center in Manhattan brought her work back into public focus.

A film made by a black woman, whose subject was—what?—a black woman philosophy professor? With a painter husband? Whose black intellectual artistic life I was trying to live myself? And, oh, these people were funny, too?

This sense of revelation, described by poet Elizabeth Alexander in the anthology’s foreword, can be extended to the collection, if not her entire body of work, which simultaneously stands as a part of and apart from a particular moment in black women’s history, a moment that inaugurated a generation of writers—Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara, Octavia Butler, Audre Lorde and June Jordan; scholars—Barbara Smith, Sylvia Wynter and Hortense Spillers; and filmmakers—Camille Billops, Julie Dash and Zeinabu Davis.

Collins’ stories are urban, contemporary and urgent in a way that contrasts to the black feminist literature of Morrison and Walker, which often evoked what literary scholar Madhu Dubey calls a ‘Southern Folk Aesthetic’, recovering versions of black community in ‘the rural South of the days of racial segregation’. Where the work of her contemporaries may have tended towards a sense of a coherent and stable past, even as they unpicked the overlooked intricacies of African American and indeed American life, Collins’ work tends more towards a disruptive and unstable present.

It is perhaps forgivable that reviewers of the collection have struggled not to use the adjective ‘sexy’, as there is arguably no better word to describe the style, form and subject of Collins’ stories: as witty and sharp as they are sensual, as irreverent as they are sensitive, as breathy as they are layered, as risk-taking as they are restrained, and as political as they are personal. Consider the opening paragraph of the titular story:

An apartment on the Upper West Side. Shared by two interracial roommates. It’s the year of ‘the human being’. The year of race-creed-color blindness. It’s 1963. One roommate (‘white’) is a Harlem community organizer, working out of a storefront on Lenox Avenue. She is twenty-two and fresh out of Sarah Lawrence. […] The other roommate (‘negro’) has just surfaced from the jail cells of Albany, Georgia. She is twenty-one and the only ‘negro’ in her graduating class. She is in love with a young, defiant freedom rider (‘white’) who has just had his jaw dislocated in a Mississippi jail. He is sitting with her at the breakfast table, his mouth wired for sound.

One of the most intriguing parts of the story is Collins’ placing of quotation marks around racial markers of difference and, perhaps, sameness (‘the human being’, ‘white’, ‘negro’), as she portrays the promises and disappointments, potential and limits of the Civil Rights era push for racial integration. Does Collins use them to indicate quotes? To express skepticism at the concept of race? Or as ‘scare quotes’ to signal that she uses the terms in a non-standard, ironic, or otherwise ‘special’ sense? There is no easy resolution. And that is the point. After all, as Collins lets us know further in this story, ‘we are swimming along in the mythical underbelly of America … there where it is soft and prickly, where you may rub your nose against the grainy sands of illusion and come up bleeding’.

Collins’ unsentimental vision no doubt draws from her cinematic sensibilities, which recall the words of bell hooks in her seminal essay on black women filmmakers, ‘The Oppositional Gaze’:

Critical black female spectatorship emerges as a site of resistance only when individual black women actively resist the imposition of dominant ways of knowing and looking. […] We do more than resist. We create alternative texts that are not solely reactions. As critical spectators, black women participate in a broad range of looking relations, contest, resist, revision, interrogate, and invent on multiple levels.

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is, then, to paraphrase poet June Jordan’s ‘Poem for South African Women’, the anthology we have been waiting for.

- Panashe Chigumadzi is a novelist and founding editor of Vanguard Magazine; follow her on Twitter

Index

Authors

- Toni Cade Bambara

- Octavia Butler

- June Jordan

- Audre Lorde

- Toni Morrison

- Alice Walker

Essays

- ‘The Oppositional Gaze’ by bell hooks

Filmmakers

- Camille Billops

- Julie Dash

- Zeinabu Davis

Films

- Losing Ground, directed by Kathleen Collins

Poems

- ‘Poem for South African Women’ by June Jordan

Poets

- Elizabeth Alexander

Scholars

- Madhu Dubey

- bell hooks

- Barbara Smith

- Hortense Spillers

- Sylvia Wynter