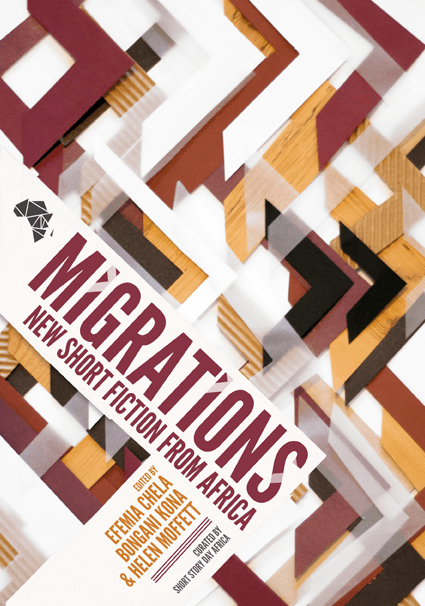

Exclusive to The JRB, new short fiction from Aba Asibon, courtesy of Short Story Day Africa. Short Story Day Africa’s latest anthology, Migrations—featuring twenty-one of Africa’s finest writers—is out now in all good bookstores in South Africa, and out in September 2017 for the rest of the world.

Things We Found North of the Sunset

Aba Asibon

Saaku ran away. Well, she did not literally run away. I watched her strut down the dusty path, carrying a frayed raffia bag, making no attempts to hide between the shrubs, lacking any fear of being caught. I looked on until all that was left of her was a speck, and until that too eventually disappeared at the point where the sky meets the earth.

She left on a Saturday because she knew our mothers would be busy with housework, and our fathers caught up in their weekend gambling under the acacias. On a Saturday, the other children would be at the weekend bazaar, pilfering sweets and trinkets with high hopes of going unnoticed. The day my best friend ran away, the sun hung low like a saffron medallion, guiding her path while I looked on with hands shielding my eyes.

Now, looking back, we should have run away together, hand-in-hand, our brown bodies camouflaged by the shrubs, because that’s what best friends do. We had heard our mothers say Eden was a long way from home: several bus and boat rides away. When they spoke of this place, they spoke of it reverently, pointing towards the horizon, north of the sunset.

Many had left before Saaku, mostly men, because the women said they could not bear to leave their children behind in search of greener pastures. Wearing their Sunday bests and carrying nothing but raffia bags filled with maize and dried fish, things that would not spoil, their families saw them off amidst prayers and tears. After several months, the travellers would send photos of themselves decked in heavy jackets that fell all the way to their knees, standing shin-deep in what looked like a blanket of white ice. Sometimes, these pictures were accompanied by short letters and crisp green bills that had to be exchanged in the city for money their families could actually use. In these letters, they said Eden was a place of abundance and that sometimes you had too much choice. Even bread, they said, came in several varieties.

Saaku and I pictured this Eden, a place with crisp green bills hanging from trees and ice falling from the sky like soft wafers. Everything we knew about this place we had heard from the families of those who had left, and Saaku’s father – who, might I mention, had never been to Eden himself. Saaku and I would sit around his radio while he listened to the news, which was usually read by a deep-voiced woman who swallowed half her words. We heard of the incredible things the people in Eden had achieved, how they had sent men to the moon and how their buildings were so high, they almost touched the sky.

“Do people in Eden die?” Saaku had asked her father once. She had a tendency to ask questions children should not ask.

Her father chuckled, which surprised us because he was not the sort of man who chuckled. “Yes, they do, but not like us. They don’t die because their doctors are on strike or because there is drought. They die because they choose to.”

Saaku and I looked at each other, puzzled. Her father was not a man of many words. Not to us. Not even to Saaku’s mother. Papa Saaku was a stout man with a stern face, who relayed his expectations succinctly and expected to be understood.

Saaku and I were fascinated by this place where people chose whether or not they wanted to die. For weeks we lay on her bed in her parent’s bungalow, comparing life in Eden with life here, where nothing really happened. Here, our money was worn and dirty, and things like milk and soap were as seasonal as fruits and vegetables.

It was at Saaku’s house that we did all the planning because she did not have siblings running around causing chaos. At my house, my parents’ seven children filled every space and every corner with shrieks, name-calling and fistfights. My mother, in between constantly doing the laundry and cooking for nine, would yell threats at us, and when she had had enough, she would grab the first child in sight, drape them over her thighs and spank them foolish.

At Saaku’s house, we could huddle on her lilac-covered bed in peace, sketching directions and making calculations in our double-ruled notebooks.

“It will cost us a whole year’s worth of lunch money to be able to afford this trip!” I exclaimed once we had tallied the figures for bus fare, food and lodging.

“No, dummy!” Saaku responded. “Only a third of a year.”

She was better at mathematics.

“I’ll find us the money,” she proclaimed.

And find the money she did, day after day, that is, until her father caught her with her hands in his wallet and left her buttocks with welts the size of baby okras.

One afternoon, while we dug twelve little holes in her backyard for a game of bao, she placed a hand on my shoulder and announced that only one of us would be able to go to Eden.

I argued against this. It would be safer if there were two of us. Saaku argued that we had only been able to raise money for one, and then offered to be the one to go. I wanted to be brave too, to offer to venture alone into the unknown, leaving behind the familiar, but I let her win; she was better at arguing anyway.

So Saaku ran away. I walked her all the way to the ridge of termite hills where our town seeps into the next. There was no need for hugs or kisses or emotional goodbyes because Saaku would soon send back money for me to join her. Instead, we hooked arms and twirled around till we became dizzy and collapsed on top of each other, laughing until there were pins in our sides.

“Write, will you?”

“Of course I will, on lavender-scented paper.”

“With a picture?”

“With a picture every month, I promise.”

We lay there in a small heap, listening to the rise and fall of each other’s chests, until the amber edges of the sun began to fade and the sunset revealed itself.

“Promise you won’t tell anyone I’m gone, or they’ll come looking for me.”

She pressed a finger to my lips, turned around and disappeared with the sun.

So later when I saw Mama Saaku crying, her hands folded on top of her head, calling for someone to bring home her only child who had not shown up for supper, I could only look on. I stood by and watched her roll herself around in the red dirt, her shrieks drawing attention and gathering a crowd. A hush fell over the town, people whispering in soft timbres, wondering what could have happened to a woman to make her pull at her own hair with such ferociousness. And once they had been briefed, they placed their hands over their mouths because such things never happened in this town.

A search party, twenty men strong, was sent out to find Saaku. They perused the area, calling out her name every day until nightfall for a whole week. They searched houses, turned the market square upside down, and cut through the thickets with their machetes. Their hunting dogs were with them, their noses trained to sniff out Saaku’s scent along the obscure trails that led out of town, and each night they came home with heads hanging low.

Our mothers became fearful; they could not sleep at night at the thought of some fiend prowling around town, stealing their children. They placed curfews on us to make sure we were indoors and under their watchful eyes before the sun took its light away. Thanks to Saaku, our mothers now looked out for each other’s children, and if they saw a child straying too far unattended, they grabbed them by the ear and returned them to their parents. Finally, the women of the town had a legitimate reason to stick their noses in other people’s business. At school, children spoke of how their fathers slept with machetes and rifles next to them, as if whoever took Saaku might dare come into our homes in the middle of the night.

When Saaku had failed to show up by the end of the week, her parents came to my house. Flanked by my father and mother, they sat me down and searched my eyes for any hint of Saaku’s whereabouts.

“Did you see her talking to any strangers that day?” her father asked.

I shook my head, avoiding eye contact.

“In which direction did you last see her go?” Mama Saaku followed, small cracks in her voice.

Mama Saaku was a nice woman, always spoiling Saaku and me with homemade baobab sweets, feeding us until our bellies stuck out. I loved her almost as much as I loved my own mother, and the sight of her sitting in my parents’ living room, shoulders slumped, made the truth dance in my throat for a quick moment before fizzling down my gut.

Our parents talked among themselves for the rest of the night. My mother, in all confidence, assured Saaku’s parents that if I knew something, I would speak up. And then, in her all-knowingness, she speculated that perhaps their daughter had wandered off and lost her way. They should consult a medicine man, she suggested. There was a good one a few towns away, who was cross-eyed and saw things the rest of us could not.

Mama Saaku touched my arm tenderly on her way out of our house, waiting until her husband was out of earshot to whisper, “Please don’t stop coming by to visit.”

The night of my interrogation, I pulled out the picture I kept hidden inside my pillowcase, the one of us grinning, our heads leaning towards each other, taken at the previous year’s harvest festival. Saaku was the prettier one, her teeth shiny white and perfectly arranged, her skin the sweet colour of coffee. Staring hard at the photograph, I noticed details I had never taken in before: a tiny mole at the left corner of her mouth, the slight dimpling in her right cheek when she smiled.

My father eventually noticed, without thinking too much of it, that I had taken a liking to his weekly post office trips. Every Saturday morning, I rode on the back of his Roadster through the crowded city centre until we reached the rows of little red boxes on the back wall of the post office. Eagerly, I watched him while he fiddled with the lock on his post box, craning my neck to catch the names on the envelopes while he scanned them. There were always religious pamphlets for my mother and stacks of bills for my father, but no lavender-scented paper for me, not yet.

The first few months after Saaku ran away, I had these recurring dreams of us in her bedroom, painting each other’s fingers with hibiscus dye, cursing loudly whenever one of us painted outside the nail boundary. The dreams were so vivid I could smell the camphor scent she always carried, hear every note of her wheezy asthmatic breaths. The dreams lingered behind my eyelids, like acts waiting for the stage lights to be dimmed, taunting me until my eyes flew open. And then, the rest of the night, I lay on my back, listening to the chorus of my siblings’ snores combined with the monotonous chirping of crickets outside.

Some nights, I worried I would never sleep again because of the deep throbbing in my chest. I feared I would go mad. I had heard stories of people who did not sleep for days until they began to talk to themselves, and when sleep finally came to them, it was for eternity. It was in those sleepless moments that I missed Saaku the most.

I also missed her on the walk to school, when the other children paired up along the footpath, kicking red earth at each other until their black shoes turned the colour of rust. I missed her during religious education classes, when our classmates passed notes back and forth, and made faces when the teacher’s back was turned. They looked at me with pity, the way you look at someone who is missing a limb. Sometimes, while I sat by myself in the playground, they came up to me and said they missed her too: her hyena-like laughter, how good she was at impersonating teachers, her sharp mouth. When you miss your best friend, you do not just miss parts of her: you miss the entirety of her existence.

These days, children are allowed to play outside past sunset, to frolic under the moonlight in the market square. Mothers no longer use Saaku as an excuse to keep their wandering children indoors to help with the housework, and our fathers once again sleep with both eyes closed. Somewhere in all of this, I have found sleep again. It comes without much beckoning, and when I fall into it, it is as if I have fallen into a deep abyss.

I visit Mama Saaku every day after school. While the other kids stay to play soccer, I sling my bag over my shoulder and trot down Tudu Lane. Some days, I find her on the front porch, engrossed in a pan of beans, sorting and flicking bad seeds to the chickens. Other days, I find her mending clothes in the backyard, humming a little tune while she works a tiny needle. Each visit begins with a cup of sweet kernel water, which I gulp down, stray droplets trickling down the sides of my mouth. The kernel water is soothing, ten times better than regular water. My parents would not approve of Mama Saaku serving me kernel water every day, something they reserve only for special guests. But my parents barely notice that I am gone, not with six other children running around the house.

At first, the visits to Saaku’s house were difficult. I would smell her through the cracks in the walls, and each moment, from the bleating of the goats in the backyard, to eating Mama Saaku’s mashed yams, was déjà vu. Mama Saaku used to stare at my movements so intently that she wept: thunderous sobs that rose from her gut and made her body tremble. During these episodes, which usually lasted about an hour or so, I did not exist. It was just her and the bare floor on which she lay sprawled, arms draped over her face. While Mama Saaku writhed on the floor, I looked around and made quiet observations: the window panes were enveloped in a thick film of dust, the dining table was clearly unused and covered with piles of old newspapers, and the walls which used to be bare, were now covered haphazardly in a child’s amateur pencil sketches. When Mama Saaku finally picked herself off the floor, she would dry the snot off her cheeks with the back of her hand and apologise. But if anyone had any apologising to do, it was I.

These days, our favourite thing to do together is to mend clothes. We sit in the backyard, tucking in loose hems, patching up underarm holes and replacing missing buttons. Mama Saaku has taught me to embroider, how to move my fingers to create delicate patterns across dull fabric. She says I am a fast learner, that while it took Saaku roughly six months to learn to embroider, it has only taken me two.

Some days, when I arrive at the house, she takes one look at me and mumbles under her breath that my mother should take better care of my hair. Hair is a woman’s glory, she tells me as she summons me to sit on the floor between her legs, undoing the four lazy plaits that have become my mother’s signature. I can feel her frustration as she pulls and tugs at my wild curls, her fingers sliding up and down my scalp, smoothing and weaving. When she is done, she hands me a mirror so I can see her work of art, my stubborn hair intricately braided into rows of submission.

“See how pretty you look,” she tells me and I feel warmth fill my cheeks.

When we are done with mending clothes, we venture into Saaku’s unaffected room, her bed still covered in lilac sheets, a small collection of toys heaped in one corner. The missionaries hand out the toys every year during the Christmas bazaar, right after they teach us songs about snow and holly, things of which we have no knowledge. The girls receive dolls and the boys get rubber footballs, and if a girl asks for a football instead, she gets scolded. Some of Saaku’s dolls are streaked with black stains from all the times she tried to dye their golden hair black with ground charcoal to get them to look more like herself.

In Saaku’s room, Mama Saaku and I keep busy, organising the closet, dusting the furniture and removing cobwebs. Sometimes, she tells me grown-up things that I struggle to understand. Once I listened to her deliberating what would be worse: if someone found a sandal that belonged to Saaku on the outskirts of town, or if nothing was ever found. She said that perhaps a sandal would give her closure. I wondered what “closure” meant. I wanted to tell her that Saaku needed both sandals in Eden, that people there would laugh if she showed up with one foot bare, but I remembered Saaku’s forefinger on my lips the day she left.

Mama Saaku makes sure to shoo me out of the house just before sunset, before her husband returns from work. She says he would not approve of her harbouring me in their house when I should be out playing with other children. My guess is, I am an unwelcome reminder of his daughter.

Before I step out of the door, Mama Saaku presses three coins into my palms and clasps my fingers over them. I have given up trying to refuse the money, because this puts her in a strange mood. The money is tucked away in the patent shoes I wear only on special occasions. Occasionally, I give myself a treat by spending a tiny bit on custard apples and dough-puffs in the market, but the bulk of the money remains untouched, waiting for the day when Saaku and I can buy tickets to see the acrobats perform at Easter.

The return from Eden begins sometime in the rainy season, two years after Saaku runs away. It begins with three, then four, then five, until eventually it seems as if our people are coming back in throngs. We have heard our parents talk about the situation in Eden, and we smell the hidden panic in their voices. They say the natives are upset that foreigners are taking their jobs, their women and their dignity. One of our own was ambushed and killed on his way to work one morning, and without a body, his mother has still not had a chance to grieve properly. The natives lurk in the shadows waiting for anyone who looks a little different, smells a little different, speaks a little different.

The other children and I now play at the periphery of our town, at the very spot where Saaku and I parted ways, craning our necks to see who would return next. They all emerge from the horizon with the same defeated demeanour, carrying nothing but the same half-empty raffia bags they left with. They come wearing those heavy coats we have seen them wear in the pictures, even though they will never need them in this climate. As soon as their shadows appear, one of the children runs back into town yelling, drawing a crowd to meet the returnees.

Each return is tinged with the same bitter sweetness: a murky mixture of relief and disappointment. There are no colourful celebrations to welcome them back; the returnees do not come bearing exciting stories to feed our hungry ears. Most of them spend their days in melancholy, sitting on their front porches, facing the direction from which they have returned. You cannot ask them if they ever saw so-and-so back in Eden, if so-and-so is still alive, because making them remember just seems so cruel. So instead, everyone sits and waits and cranes their neck towards Eden.

The other children stretch their necks out of curiosity, to have something to point at and gossip about, but me, I stretch my neck each time hoping to catch a glimpse of my best friend. I wonder if she too now has breasts the size of small tangerines jutting out of her chest, and if she too has started to feel funny things for boys. I have so many questions for her. Why did she never write? What was Eden like? Did their money really grow on trees? Did she ever find out what people there died from? Most importantly though, I would ask her why she burdened me with keeping this heavy secret.

Sometimes, while Mama Saaku and I sit in the backyard mending clothes, we stop to look at the hens peck lovingly at their chicks. Our eyes follow the brown baby goats running to nuzzle their mothers and I wonder what is going through Mama Saaku’s mind. Often, I feel the need to put her out of her misery, and each time I come to a quiet resolve: that this is not my story to tell. One day, when Saaku finally comes back among a throng of returnees, she will see that if there is one thing I am better at, it is keeping a secret.

- Aba Asibon is a Ghanaian writer whose short fiction has been published in Guernica, The University of Chester’s Flash Magazine, and African Roar. Aba has also had poetry featured in the Kalahari Review and was longlisted for the Ghana Poetry Foundation’s debut prize. She currently lives in Malawi, where she works on public health initiatives to improve healthcare for newborns.

This is an enticing story. Loved it!

Well written, Aba. The vivid description and use of figurative language really draws one into the story