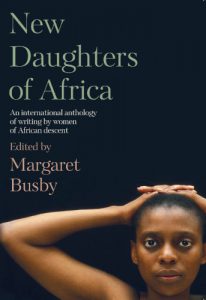

In celebration of Women’s Month, The JRB presents a series of excerpts from New Daughters of Africa.

Edited by Margaret Busby, New Daughters of Africa is an anthology of the work of more than 200 women writers of African descent. It follows on from Busby’s seminal 1992 book, Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by Women of African Descent from the Ancient Egyptian to the Present.

In the August issue of The JRB, enjoy Danielle Legros Georges’s poem ‘A Stateless Poem’, an excerpt from the much-anticipated English translation of Angolan-Portuguese writer Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida’s debut novel That Hair, and this essay, by Afua Hirsch, ‘What Does it Mean to Be African?’

A writer, journalist and broadcaster, Afua Hirsch was born in Norway, to a British father and a mother from Ghana, and was raised in Wimbledon, London. She studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Oxford University before going on to take a graduate degree in Law. She worked in international development in Senegal, practised law as a barrister in London, and was West Africa correspondent, based in Accra, Ghana, for The Guardian newspaper, where she is now a columnist. She was the Social Affairs and Education Editor for Sky News from 2014 until 2017. She writes and makes documentaries around questions of race, identity and belonging—the subject of her 2018 book Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging.

Read the essay:

~~~

What Does It Mean To Be African?

What does it mean to be African?

Some would define it, I think, as simply being someone who doesn’t feel the need to ask that question. Isn’t it a question only an outsider would ask? What kind of black person, I recalled being asked, in one of the lines in my book Brit(ish) that people seemed to find most entertaining, writes a book about being black?

I am a black person who writes a book about being black. I am an African who agonises over what it means to be African. I quote Kwame Nkrumah—who as president of Ghana led the first black African country to win independence—because he tells me what I want to hear: that I am African because I choose to be.

I am not African because I was born in Africa, but because Africa was born in me.

I listen to Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah—the title means victorious in battle—and I listen to all the sages. Maya Angelou told me it was a question of knowing your past:

For Africa to me … is more than a glamorous fact. It is a historical truth. No man can know where he is going unless he knows exactly where he has been and exactly how he arrived at his present place.

Down the road from Wimbledon, the south-west London suburb where I grew up, the British–Trinidadian poet Roger Robinson said—writing in the heart of Britain’s black community—it was a question of mental integrity, and purpose:

People talk about toxic waste

(Roger Robinson, The Butterfly Hotel, Peepal Tree Press, 2013, p. 17)

being dumped in Africa, but toxic

waste has already been dumped

in your minds. Some of you don’t know

how you came to be in Brixton. Hell,

some of you don’t know you’re African.

But maybe the words that haunt me most come from an earlier time. This exchange between expatriate American author Richard Wright and JB Danquah—one of the architects of Ghana’s independence over decades of activism in the early twentieth century—is etched into my memory. They met during Wright’s visit in 1953 to the then Gold Coast and Wright recounts in his book Black Power that Danquah starts by asking:

‘How long have you been in Africa?’…

(Wright, Black Power, 1954, pp 218–19)

‘About two months,’ I said.

‘Stay longer and you’ll feel your race,’ he told me.

‘What?’

‘You’ll feel it,’ he assured me. ‘It’ll all come back to you.’

‘What’ll come back?’

‘The knowledge of your race.’ He was explicit.

I liked the man, but not as a Negro or African; I liked his directness, his willingness to be open. Yet, I knew that I’d never feel an identification with Africans on a ‘racial’ basis.

‘I doubt that,’ I said softly.

What does it mean to ‘feel’ African?

That’s not the same as what it means to ‘feel Africa’. Tourists do that every day—exposing their senses to the immersive bath of sound, smell and energy, and finding it thrilling. I just love Africa, it’s SO colourful! The people are SO friendly! The bustle has SO much energy! The food is so spicy! …

Everything my parents had to do required hard work: buying a house, raising money for school fees, creating the kind of home environment in which they thought—rightly—my sister and I would be able to experience joyful childhoods and emerge as functional, accomplished adults. My mother worked hard at everything, except sustaining an African identity, which seemed to require no effort at all. She has spent most of her life in a place that—as is the way of Britain—performs whiteness without knowing that whiteness is what it is. The leafy London suburb where I grew up is not multicultural like the rest of this great city of cultures, languages, cuisines and slangs; it is chronically preserved in a detached house, fruit-tree-populated lawn kind of Englishness, so attractive it has been commodified—in the guise of lawn tennis, and inflated property prices—and exported around the world. But my mother has navigated this locality, as is the way of her generation, surviving, without fussing or even vocalising the intensity of the experience, journeying silently to the nearest black place for hair products or fufu flour, fulfilling the functions of the eldest child in an Akan family, nursing herself on light soup when sick.

I don’t think it occurred to either her or my father—who is British, and white—that Africanness was something that would be relevant to me. And so preserving for my generation a connection with our African heritage was not part of my parents’ deliberate thinking. They were both secure in their own identities, which were cultural and national rather than racial. Identity was not the primary struggle of their lives—there were plenty of material things to worry about—and ours would take care of themselves.

But identities take on different strains when planted in new soil. It didn’t occur to my parents that a mixed-heritage child, labelled casually as ‘black’ by the loaded gaze of a white society, would crave substantial, positive messages about the source of her blackness. They did not know what it was like to be born and raised in a place where your identity is defined as a minority—by a sense of otherness and difference. They didn’t foresee that beneath the blackness with which I was labelled, I—the second- generation, mixed-heritage, British girl—would feel my race. I was African. At least, that was my dream.

What did it mean to be African? Is it to bear a name?

Africans from the diaspora, reversing in the wake of the slave vessels by returning to the continent of their blackness, often find, when they land on African soil, that the first thing to do is to take a name. Some take on mine, if they were born on a Friday, as is the Akan way. Ghanaians often think, when I introduce myself by name, that I am African–American or Caribbean and have latterly chosen a new label for a newly African identity. My name is Afua, I say. Oh! Are you sure? they reply. You know what that name means? They school me. It’s a lesson that causes me to wince. British people massacre my name. Ghanaians simply don’t believe it is mine.

Is being African to live in Africa?

I thought it was. And I returned to the idea, like a creature bound by homing, that to heal one’s identity was to journey to the place from which it springs. So one day, in my early thirties, bundling my then six-month-old daughter against the London snow, I packed up and moved to Ghana. My daughter would know this land first- hand, I decided, not as a narrative filtered through the British gaze, the still stale mess of a hopeless continent, ahistorical and doomed. She would, unlike me, understand the Ghanaian seasons and festivals, the pattern of a week where the emptied streets pour into churches on Sunday, where offices hum to the clash of local prints on Friday, where cryptic hand movements indicate the destination of a tro-tro bus, and where the fading of the light and the rising spice of kelewele frying fall with the rhythmic certainty of sunset. Maybe this would make her African, and—whatever happens to me—I will have given her that gift.

Is being African learning to speak?

Language gives structure to our thoughts, a fact not lost on the architects of the European imperial project of breaking the African spirit and disbanding the historic and cultural continuity of the peoples they overran. When I read of the short story by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o ‘The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright’, published in an unprecedented forty-seven African languages—a much needed attack on what Ngũgĩ describes as the problem of ‘intellectual production in Africa [being] done in European languages’—I applauded. Then realised that I, of course, would be reading it in English. And if the route to casting off the colonial legacy is embracing our African languages, where does that leave those of us—like me—who can’t speak any? Learning to speak—and hence think—in a different way, may be the project of my whole lifetime.

My understanding of what it is to be African has been a process of elimination. I have been named in Twi, I have eaten light soup. I have worn kente and ankara, I have lived and worked across the African continent, I have studied languages, I have observed and repeated gestures, and intonations, rituals and gaits. I have done these things and they have shaped me. But if there is a tipping point at which the conditioning of this colonial power that raised me slips over into the African conditioning that I want to shape me, I don’t know where it is.

The problem with the cultural delineations of what it means to be African is the temptation to fall into the trap created by the white gaze in which people like me have been immersed for most of our lives. Can we really escape the imperially stained nostalgia for the perceived Africa of the past—that loaded longing for a primordial world—that classic symptom of true outsider-ness? It is so tempting a tonic for those like me, who wish to connect with the Africa of their parents’ memories, preserved as an antidote to an immigrant life in a hostile host nation, and who feel sentimental about the communal flow of life in the village where we have never actually lived. Our cousins who do live in the village are not romanticising ideas of ‘Africa’. They are rooted in communities, regions and nations where the hustle is king—finding the power to charge their phones, struggling through school lessons taught by barely literate teachers, or trying to import Chinese fridges. They are urgently inventing the new.

No one is waiting, breath bated, for us to define what it means to be African. Yet still we continue to search for a reason to ask the question, for hope that an answer exists. And for a sense of purpose. ‘Africa,’ said John Henrik Clark, the Pan-African historian, ‘is our centre of gravity, our cultural and spiritual mother and father, our beating heart, no matter where we live on the face of this earth.’ Being African is to believe it. At least that’s what being African means to me.

~~~

Afua is solely focussed on what she perceives to be the positive, affirmative aspects of being African; but there are darker sides. Consider the below below..

Slavery existed among the Igbo long before colonization, but it accelerated in the sixteenth century, when the transatlantic trade began and demand for slaves increased.

Under slavery, Igbo society was divided into three main categories: diala, ohu, and osu. The diala were the freeborn, and enjoyed full status as members of the human race. The ohu were taken as captives from distant communities or else enslaved in payment of debts or as punishment for crimes; the diala kept them as domestic servants, sold them to white merchants, and occasionally sacrificed them in religious ceremonies or buried them alive at their masters’ funerals.

(A popular Igbo proverb goes, “A slave who looks on while a fellow-slave is tied up and thrown into the grave should realize that it could also be his turn someday.”)

The osu were slaves owned by traditional deities. A diala who wanted a blessing, such as a male child, or who was trying to avoid tribulation, such as a poor harvest or an epidemic, could give a slave or a family member to a shrine as an offering; a criminal could also seek refuge from punishment by offering himself to a deity. This person then became osu, and lived near the shrine, tending to its grounds and rarely mingling with the larger community. “He was a person dedicated to a god, a thing set apart—a taboo forever, and his children after him,” Chinua Achebe wrote of the osu, in “Things Fall Apart.” (The ume, a fourth caste, was comprised of the slaves who were dedicated to the most vicious deities.)

In the nineteenth century, the abolition of slavery in the West inadvertently led to a glut of slaves in the Igbo markets, causing the number of ohu and osu to skyrocket. “Those families which were really rich competed with one another in the number of slaves each killed for its dead or used to placate the gods,” Adiele Afigbo, an Igbo historian, wrote in “The Abolition of the Slave Trade in Southeastern Nigeria, 1885–1950.”

The British formally abolished slavery in Nigeria in the early twentieth century, and finally eradicated it in the late nineteen-forties, but the descendants of slaves—who are also called ohu and osu—retained the stigma of their ancestors. They are often forbidden from speaking during community meetings and are not allowed to intermarry with the freeborn. In Oguta, they can’t take traditional titles, such as Ogbuagu, which is conferred upon the most accomplished men, and they can’t join the Oriri Nzere, an important social organization.

Westerners trying to understand the Igbo system often reach for its similarities with the oppression of black Americans. This analogy is helpful but imperfect.

Igbo discrimination is not based on race, and there are no visual markers to differentiate slave descendants from freeborn. Instead, it trades on cultural beliefs about lineage and spirituality.

The ohu were originally brought to their towns from distant villages. Community ties are very important in Igbo culture, and so, while the descendants of, say, American immigrants are encouraged to assimilate, the ohu have never lost their outsider status. With the osu, the diala originally believed that mixing with a deity’s slaves would earn them divine punishment. (In its spiritual aspect, the plight of the osu is similar to that of dalits in India or of burakumin in Japan, whose ancestors are believed to have done “polluting” work as butchers or tanners, and who are therefore thought to be impure.)

With Christianization, the conscious aspect of this belief dissipated, but not without leaving traces. “The fear people have is: before long, our children and children’s children will be bastardized,” Okoro Ijoma, a professor of Igbo history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, told me. “It is about keeping their lineage pure.”

Perhaps the most important difference is that, though abolition in the West was preceded by centuries of activism that slowly (and imperfectly) changed popular attitudes, abolition in southeastern Nigeria was accomplished by colonial fiat—and only after the British no longer had an economic stake in the trade.

It therefore seemed to many diala to be as arbitrary and self-serving as when the British pushed the Igbo, in the nineteenth century, to abandon subsistence farming in favor of cultivating cash crops, such as palm oil. The institution of slavery ended, but the underlying prejudices remained. In 1956, the legislature in southeastern Nigeria passed a statute outlawing the caste system, which then simply went underground.

“Legal proscriptions are not enough to abolish certain primordial customs,” Anthony Obinna, a Catholic archbishop who advocates for the end of the system, told me. “You need more grassroots engagement.”

No data exist on the number of slave descendants in southeastern Nigeria today; it is rarely studied, and the stigma often compels people to keep silent about their status. (Ugo Nwokeji, a professor at Berkeley who studies the issue, estimates that five to ten per cent of Igbos, which would mean millions of people in Nigeria, are osu, and likely an equivalent number are ohu.)

Recently, slave descendants have begun agitating for equality, staging protests and pressuring politicians. In 2017, the governor of Enugu State spoke out against the discrimination, saying that it violated the country’s constitution. In Oguta, ohu have distributed pamphlets and sued diala family members who tried to block them from receiving what they considered to be their inheritances, including access to communal farm land.

Two years ago, when an elderly ohuman was snubbed for a seat on the village council, the ohu held a parallel ceremony to install him in the position. The ceremony was invaded by diala, who caused a brawl that the police had to break up. “Their population is much higher than ours,” Okororie said. “That is our only handicap.”

Now perhaps read VS Naipul’s book – The Masque of Africa.

Africa is not, and never has been some idyllic interpretation of Ubuntu, and romanticising it as such is every bit as corrosive as Afua’s obsession with “whiteness”.