There is an ‘undecidable conflict’ between the poet’s desire to sing an alternative world and, as Grossman puts it, the ‘resistance to alternative making inherent in the materials of which any world must be composed’.

—Ben Lerner, quoting Allan Grossman

Collective Amnesia

Collective Amnesia

Koleka Putuma

Uhlanga Press 2016

Bongani Madondo on the strange musicality of Koleka Putuma’s debut poetry collection

1.

First time I met Koleka was at my book launch at The Book Lounge in Cape Town. Names were not exchanged: just eye gestures. Close/distance acknowledgement and sizing up of like-minded or like-blooded species.

I don’t remember saying a word to her, or her to me. As these things go, we repaired to a joint going by the name of Lefty’s, where I assumed only sooty Marxists types hung out, or dreadlocked brothers with white women with metal-like stuff sticking out their noses, sprouting words like: ‘mah china, how dee, you from Joooh-berg? You Joooh-bergers are full of shit, you are all celebrities and no one creates real art’.

It turned out to be a lovely, noisy joint with even lovelier waiting staff, women all sporting Angela Davis-esque Afros in myriad stages of Black Power progression—up to Black Panther poster-worth dimensions—and none of them asked me if I am from ‘Jooh-berg’ or not. And yet, Koleka and I never really connected.

There was just something about her I couldn’t quite put my finger or mind on. So ignorant am I, it never even registered she’s a poet, although she had that bohemian look Cape Town people wear with pride.

Next time I lay my peepers on her is at the groundbreaking Abantu Book Festival in Soweto. The atmosphere is some kind of African-healing/punk-rock séance or some secretive all-Afro Jedi sect in dire need of self-cleansing and displaying its laundry to itself.

Throw in some stylings and posing (intellectually and sartorially), as well as some really transformative gestures and interventions on topics ranging from The Quiet Violence of our Nation to Writing and Rioting: Black Womxn in the Time of Fallism to Kind of Blue: Jazz Beyond its Musical Form, and so on, and you have an idea how it went down last summer.

And yet I’m not able to connect nor am I trying to connect with Koleka. She wears a permanent don’t fuck with moi attitude people who know they are pretty gifted often slide in and out of. And I might be wrong. It all doesn’t matter. Scratch all the above. Small talk carries a fetid smell of unrealised yearnings. What matters is what she does on the panel, the one with the phrase ‘decolonial’—uhm, ah I know, maybe it did … maybe it didn’t—which we are both sitting on, together with Lidudumalingani Mqombothi and Rehana Rossouw.

It’s held in a stewing pot of a venue. It’s filled to the rafters. Fallists are here in numbers. Among them are adults dotted within the young garde. The session quickly morphs into a deeply painful catharsis. Yet freeing. It’s a cleansing stomp. We well up. At least I do. Some in the audience are just as affected. Senzeni Afrika?

When it’s time for her turn to speak, Koleka reads/recites ‘Graduation’, a poem from an as-yet-unreleased collection. Collective Amnesia is the title, it later transpires. Voice assured. A storyteller’s cadences. No preaching. No scolding. No fire and brimstone. Her voice is rhythm tightly controlled like a jazz scat master’s; it’s like the coiled innards of a brand-new golf ball. As she reads, her soul, and ours, uncoils and takes flight:

You will leave your parents’ nest

Cultivate familiar traditions borrowed from your childhood

You will realise none of it is new or yours

You will work and send money home

You will work and not send money home

Earning money will earn you a seat at the grown-ups’ table

Contributing financially will allow you to open your mouth at the grown-ups’ table

Silence in the joint. Breaths held in check. This is not some cute retort to the shackles of what they call the ‘Black Tax’.

But you will still watch your mouth at the grown-ups’ table

When you return home

You will slip into roles you have outgrown

Because it’s easier than explaining

Extracting lines from a poem can feel like an exercise in dismemberment. You wish the reader was there to hear it, or read the darn thing in its entirety. So I am not doing justice to the power and quiet force through which she’s reciting it. To the manner in which the words dance and dangle off her tongue and land with that thwak! in your soul.

Still, listen to this:

… When your parents visit

You will prepare their room

And hide all the things they probably know or suspect about you

Your mother will offer to help with the cooking

The way she chops the onions is loaded with questions

You both have not mastered how to chop onions without crying

Chopping onions that way is how you have difficult conversations

You have both learned how to dance on graves

I’m pro’bly sacrilaging both the poem and the poet here. In verse and in performance she leaves no room for cute stanzas. Her work is tight and compact, yet eschews denseness. When she finishes … well, she doesn’t, the poem doesn’t come to an end. It travels in our psyches and rests deep in our tummies. We breathe hard.

In/Out … In/Out.

Heaving. Almost.

I hear someone in the crowd doing a bad job at whispering to his mate: Who’s that girl? At that stage I too didn’t know the half of it.

2.

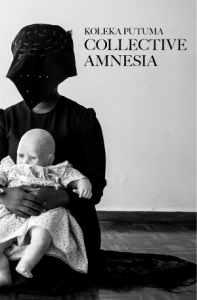

Third time I met her was on the page, five months later when Collective Amnesia landed on my desk straight from the Mother City. Its black-and-white cover announces the content and the author in dramatic imagery.

On the front cover, and played against ice cold backdrop whose white has gone cloud-grey, is the figure of a black woman, who might or might not be the poet. She’s seated on a bare parquet floor, feet bare, face veiled in a black designer isiXhosa cloth.

She is clutching tightly but not so obviously tenderly a life-size doll of a chubby white baby, who could be allegorised as the poet’s daughter or, more likely, her white bosses’ daughter, a story in an image of a long, tragic tale of black women raising white folks’ chirrun as theirs, while being kept away from theirs. On the other hand, this could be an over-reading of the imagery. Make what you will. For me, the cover recalls the artist Mary Sibande’s famous blue- and, later, purple-clad domestic-worker-turned-heroine, Sophie.

The collection’s back page is an extension of the front although the white in the backdrop is whiter. In the inside fold, just as with some publicity shots doing the rounds on social media, is a still clip of the poet in action. Her hands gestures wildly in prayerful performance.

Wet white dress clings defiantly to her upper body to reveal in stark detail two perfectly formed balls of breasts, nipples daring the viewer to sexualise the image.

Whichever way you look at it, however deep or (mis)educated in gender or feminist theory you might be, the white wet dress tableaux is charged with entrancing, mystical eroticism.

Mystical because, like Busi Mhlongo in the Revel Fox-directed and least-known bio-doccie of her shamanic process, or like Cassandra Wilson on the cover of her album, ‘New Moon Daughter’, Koleka is a water/sea mystic.

The image, like her elegantly spiky verse, is one of the bravest, most daring images since the folk-rock poet Patti Smith looked boyish yet flaming hot/on yer-face while boldly unattainable on the Robert Mapplethorpe-shot portrait on the cover of her debut album, ‘Horses’, circa 1975.

A week later when preparing this screed I called the poet to ask if I can use ‘titties’ or whether she comfortable with ‘breasts’ in my description of the imagery. ‘Breasts’, she cautioned, ‘but it depends on the context’. Thus, breasts in. Titties out.

For those still in need of a précis to answer the question Who’s that girl? the bio gives more away. Barely. But, ja. Koleka Putuma was born in Port Elizabeth in 1993, it says. An award-winning performance poet, facilitator and theatre maker, it says … not ‘playwright’, ‘actor’, ‘director’ or ‘producer’, but ‘theatre-maker’. Her work has travelled around the world, garnering her national accolades such as the 2014 Poetry Slam Championship and the 2016 PEN South Africa Student Writing Prize. She currently lives and works in Cape Town.

‘Theatre-maker’, it says.

Carry these words as you consider ‘Coming Home’, from Collective Amnesia:

This one time,

in your office,

spread reckless across your deadlines,

we made love like we were chased by wolves,

like the wolves were on your desk with us,

like the wolves were on our hands,

circling around our clits, and dripping down our legs.

Like the wolves in your mouth, devouring all flesh and bone.

My late friend K. Sello Duiker, a lover of magical-realist verse, would have been animated by this. He’d have hounded the name Koleka, chasing it down Cape Town’s alleyways. Past fawning and self-adoring European tourists’ beach-fronting on Mouille Point. Chasing it and its owner past the Somali Muslim traders down Greenmarket Square, which is anything but scenic-ly green. Past the colour(ed) drippin’ facades of the now-unaffordable Bo Kaap houses pouting defiantly against the Cape Easterly and the smell of the nouveaux riche, down the taxi-rank from whose bowels ring sounds of click-clickety tongues.

I can imagine him, Afro shooting skywards, stalking her right into boho enclaves such as Observatory where, perhaps, the chaser and the poet would entangle giddily, lekker-gesuip, in one of the jazz joints with names such as The Mahogany Room or Straight No Chaser.

Me? I read it twice and my breath skipped and heart did its ribcage beat-dance and ran off as though chased by wolves. The climax of it all sledgehammers you with disconcerting beauty. Nina Simone’s kind of choke-hold-over-your-soul beauty:

I didn’t know how wild I could be until you touched me.

I didn’t know coming could be an act of survival, too.

Thixo! Uya bhal’ uKoleka, nyani!

The thing about Koleka is that her words and the space out of which they issue, all slips and slides, don’t make a run to your heart. It’s not her business to appeal to you, The Reader. She’s charmingly anti-poetic. She fucks with set rhyme schemes, iambic pentameter and melody. She’s the most anti-rhythmic yet musical poet I have encountered on page in a while.

Her work is dipped deep in the dungeons of ekphrastic verse, where it performs and and shuns melodrama all at once, making its musicality undeniable. Speaking of the English Romantic poet John Keats—whom the very act of referencing is tantamount to suicide—the literary scholar and author of White out: The Secret Life of Heroin Michael W Clune has this to say: at the heart of his poetry lies ‘images of virtual music’.

What is Koleka’s work? Music … drama … still photography, fuelled with life-enhancing breath.

While she is more Rimbaudian in pose, prose and posture, and while as a young black poet she clearly works, whether consciously or unconsciously, in the tradition of the likes of Medupe poets, or Ursula Rucker even—certainly while she flips and decks her heart-hitting lines with architectural loftiness reminiscent of the West Coast Beat Poet Bob Kaufman—you will understand why it distresses me no end to have to revert to the dead white man to refract and re-place, both Keats and Koleka.

If you are in anyhow interested in lyricism that is anti-rhythmical, you might be inspired to look at Koleka’s work in relation to, say, the dramatic prose-song dialogue conjured by Okot p’Bitek in Song of Lawino and Song of Ocol. Or perhaps you might wish to remain within the feminist project and look at the work against the enraged subtlety of Diana Ferrus. Neither would be out of kilter.

In retrospect, Diana Ferrus—particularly in her most famous poem, ‘A Poem for Sarah Baartman’:

I’ve come to take you home—

home, remember the veld?

the lush green grass beneath the big oak trees,

the air is cool there and the sun does not burn.

Feel the temper and tempo rising, within the near-bursting gates of a poet’s discipline, a subjective and pleasantly reportorial device funnelling the artist’s disgust, also a trait the more seasoned Ferrus shares with the young buck:

I have come to wrench you away—

away from the poking eyes

of the man-made monster who lives in the dark

with his clutches of imperialism

who dissects your body bit by bit

who likens your soul to that of Satan

and declares himself the ultimate god!

3.

It is too tempting and too narrow to draw easy lines of stylistic, temperamental and like-gendered sisterhood between the young and older Cape Town poets. Still, like Ferrus’ work, Collective Amnesia is distinct for its fierce anti-tonality.

If you are keen on dancing further with this critique, then it is no harm to hark back to Keats again. In his essay on poetry and reasons to dislike it, ‘Diary’ (London Review of Books, 18 June 2015), author Ben Lerner finds himself less than enamoured with Keats’ most mellifluous odes. Comparing Keats to Emily Dickinson, whose ‘distressed metres and slant rhymes enable you to experience both extreme discord and a virtuosic reaching for the music of the spheres’, he finds Keats wanting.

He’s right: virtuoso that he was, Keats still reached nowhere near the discordant thrust, the heavy-metal-rock-like dissonance that Dickinson and, centuries later, a band of black poets managed to attain, the latter through this thing called Slam. But unlike, say, the likes of Saul Williams and Lesego Rampolokeng, Koleka’s Slam is not grounded in, nor does it work within, the Hip-Hop or Bluesology traditions. She’s her own woman. Like Dickinson, she’s an anti-Romantic for our times.

Much as I’m bewitched by her poetry, it is far from being perfect. Very little in poetry is. There are a few dummy runs in Collective Amnesia, i.e., ‘Lifeline’, a heartfelt but misplaced ode to heroic women, which simply is not poetry, bad or good. There are a few other qualm-giving moments, too, such as the nerve-jangling feeling that occasionally settles over you as you read, a voice whispering that all Koleka really wants is to write is straight-out poetry and not verse, and so she sometimes gets stuck in the middle.

But this does nothing to dim this woman-poet’s worth. She’s not so much master of an art form as she is a master of conveying feelings, filtered through sharp social and sexual critique.

There’s much to adore in a young poet whose work distills wit, social commentary, and abstract magic, yet still comes across as unable to show off. Her aloofness on page and in person is a reflection of an artist who suffers no fools. It is not being rude. It is not ‘knowing her value’ as a woman, child, sister, sibling, artist, and so on ad nauseam, at this time when identity and likability are tradeable commodities. It is, instead, an irresistible detachment that at the same time renders heartfelt feeling:

[from ‘1994: Love Poem’]I want someone who is going to look at me

and love me the way white people look at

and love

Mandela

A TRC kind of lover.

You don’t love until you have been loved like Mandela.

4.

Koleka is not known to be Cape Town’s—and possibly South Africa’s—ruler of the under- and overground poetry scene for nothing. The poetic alter-Negro of Daenerys Targaryen, Khaleesi—the no BS-brooking ‘mother of dragons’ in Game of Thrones. Although gifted with a sharper tongue.

It all accrues to this: This sister is stamping and stomping her place across creative spatialities quite assertively. There’s no way of invisibilising her. Or her work. Even if you wished. And why would ya?

She’s a glorious anomaly, too. A performance Slam word-slinger who can run with the writing hounds. Less Dickensian than Dikeni-scion in her approach to art: a performance maven who can actually write.

In matters of written and oral literature, much of spoken-word poetry simply doesn’t hold up well on page. The stuff coming out of hipster joints, reeking with suppressed whiffs of weed and whiskey, emboldened by borrowed tongues trained in what used to be mistook for ‘good schooling in white suburbs’, tends to be a stewing pile of shit.

But while she’s also definitely a generational poet, of her time even, Koleka is as shockingly fresh and real as they come. As someone who is not steeped in queer politics, she rips my gut open when she writes:

[from ‘Memoirs of a Slave & Queer Person’]I don’t want to die

with my hands up

or

legs open.

- Bongani Madondo is Contributing Editor and the author, most recently, of Sigh, the Beloved Country: Braai Talk, Rock ’n’ Roll & Other Stories.

Index

Authors

- Alan Grossman

- K. Sello Duiker

Artists

- Mary Sibande

Awards

- 2014 Poetry Slam Championship

- 2016 PEN South Africa Student Writing Prize

Books

- White out: The Secret Life of Heroin by Michael W Clune

- Song of Lawino by Okot p’Bitek

- Song of Ocol by Okot p’Bitek

Cape Town Scene

- Lefty’s

- The Book Lounge

- The Mahogany Room

- Straight No Chaser

Essays

- ‘Diary’ by Ben Lerner

Festivals

- Abantu Book Festival

Films

- ‘The Life of Sia’ / ‘Song for Three Women’, directed by Revel Fox

Journals

Music and Musicians

- Busi Mhlongo

- Horses by Patti Smith

- New Moon Daughter by Cassandra Wilson

Poems

- ‘A Poem for Sarah Baartman’ by Diana Ferrus

Poets

- Emily Dickinson

- Sandile Dikeni

- Bob Kaufman

- John Keats

- Rimbaud

- Lesego Rampolokeng

- Ursula Rucker

- Saul Williams

- The Medupe Poets

Television series

- Game of Thrones

Topics

- Bluesology

- Romanticism

- Hip-Hop

- Slam

_____

Photos: Jarryd Kleinhans (main); Andy Mkosi (book cover)