The JRB presents an excerpt from City Editor Niq Mhlongo’s new novel, Paradise in Gaza, out on 20 October 2020 from Kwela Books.

Mhlongo will be discussing his new novel with Zukiswa Wanner in a virtual event hosted by the Goethe-Institut on Saturday, 10 October 2020. Details here.

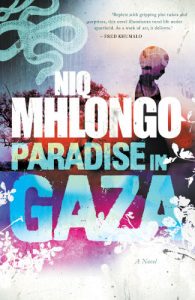

Paradise in Gaza

Niq Mhlongo

Kwela Books, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Chapter 2

The train entered the dark tunnel through the mountains. Mpisi belched the cow hooves that his wife, Ntombazi, had prepared for him and his son the previous night. It became dark inside the train. There was silence, not even a cough. No one moved or said anything. The windows of the train were all closed. The passengers had heard the myth that there was a huge snake that would remove them from the train by force if they dared to talk in the tunnel. Another legend was that if you threw a needle between the tracks, the train would derail. They were just being cautious.

As soon as the train had passed through the tunnel, the wild beauty of the forest dazzled Mpisi and his son’s eyes. Giyani smiled shyly at his father, clearly observing the uncertainty on Mpisi’s face. The eight-year-old boy was pretty in a delicate way. At school in Chiawelo he was often mistaken for a girl by his teachers. He even had the silvery voice of a girl, along with a mild stammer. Mpisi and Ntombazi were very worried about his voice. Mpisi had even suggested sending Giyani to the inyanga to see if there was something wrong with him.

As he turned his face away from his son, Mpisi wished once more that Ntombazi could have come to the burial with them. But she was due to give birth any day now. Ntombazi had convinced Mpisi that they could not take the chance of their second child being born in a rural area where there was witchcraft and few opportunities.

‘Being born in a rural area is like a curse,’ Ntombazi had said boldly, facing him in their living room in Soweto. She had looked him in the eye even though this was a sign of disrespect. ‘At least here in the city there is hope of a better future. You can find a job here unlike in the rural areas where all you can do is look after your father’s cattle and consider it wealth.’

‘Having cattle is wealth. Also, any black person simply has fewer choices under this apartheid government. It has nothing to do with whether a person was born in the urban or rural areas,’ Mpisi had tried to reason with her. Sometimes he liked her feistiness but at other times it was just too much. ‘We have to settle for what is on offer from Vorster’s government. What lies ahead of us, not even God knows.’

‘Stop fooling yourself, Mpisi Mpisani.’ Ntombazi had shrugged—a hopeless gesture. ‘You told me that you came here in 1968, a year before your homeland capital of Giyani was founded. That is why you named our son Giyani. Is that not so?’

‘Yes, but—’ Mpisi had noticed their son poking his head around the doorway when his name was mentioned.

‘But still today, nine years later, you don’t have citizenship status of Johannesburg.’

‘Of course I’ve been here since 1968. But I was only registered in 1970 when I found the job at the Republic Umbrella Company.’

‘You see what I’m trying to tell you?’ Ntombazi had opened her palms. ‘Even now you’re still regarded as a foreigner in the city of Johannesburg because of apartheid laws. I don’t want my children to suffer like you do. I want them to have citizenship. Just look at your situation now.’

Mpisi’s situation was that he did not qualify yet to be a citizen of the city of Johannesburg. Because he had been born in the village, he had to work as a labourer in Johannesburg for ten consecutive years for the same employer—a white employer—to earn citizenship. He had not yet achieved this.

‘I know that,’ Mpisi had admitted to his wife, sitting down on the couch. ‘But sometimes the worst is the best that can happen. In the meantime we have to stick to our little strategies of survival like we have been doing. We must not lose hope. There is some hope, you know.’

‘There is no hope, my husband Mpisi Mpisani. No hope at all, under this apartheid,’ she had repeated, screwing up her eyes. ‘Beyond today there is only the darkness of the unknown. This country is full of too much suffering and so much anger.’ She had remained standing while he sat and Mpisi had decided to ignore the disrespectful gesture.

‘What do you mean there is no hope? We have to try and make the best of even the worst situation. God will always be there to listen to us.’

Ntombazi had thrown her hands in the air. ‘Stop dreaming, Mpisi. God withdrew from helping black people nearly thirty years ago when I was born. To be precise, in 1948 when the National Party took control of the country. You must keep that in your mind when you start dreaming and hoping. God’s ultimate act of betrayal and supreme failure here on earth was in 1948 when apartheid was born. It is also the reason you cannot get city citizenship.’

‘At the moment I’m least concerned about my city citizenship status. All I want is for us to go and bury my mother together.’

‘I can’t go with you, and I told you my reasons. What if I give birth in the village? My baby will be classified as a rural citizen by law. It will be difficult for my child to live with us with that village citizenship.’ She had folded her arms over her pregnant stomach.

‘What’s wrong with that?’ Mpisi had insisted. ‘Gaza Village is also my children’s roots, after all. That’s where I come from. I have one child there already—’

As always when he started to mention his first wife and son, Ntombazi had cut him off. ‘Not my unborn baby. It is good that my Giyani was born here. But imagine having two children, and having them separated because one was born in the city and one in a rural area. Separated even though they are in the same country. And when my second-born can someday finally come to the city to work, deportation will be there like a threatening shadow. Look how you’re struggling. They can deport you to your Gaza Village at any time. I don’t want my baby to be vulnerable like you are.’ Ntombazi had noticed Giyani in the doorway too and had beckoned him over. As he stood next to her, she had put her hand on his shoulder.

‘Sometimes those vulnerabilities are what make life worthwhile. What if I don’t want to be a city citizen?’

‘No, Mpisi, it is not a question of choice here,’ she had said scornfully. ‘You don’t have one, and you know it. That’s why you have kept that newspaper page with the notorious Section 10 of the Urban Areas Act under our mattress for all these years.’

‘I know that. But we always have a choice as human beings. A man doesn’t get too old to hope.’

‘What choice is there, Mpisi? You mean proving that you have been living in Johannesburg continuously for fifteen years, which you have not?’ She had started to pace up and down, one hand at her back and the other holding onto Giyani. With her protruding belly she could not move as quickly any more. ‘What about your friend Mzila who was charged for loitering with suspicious intent when he could not find a job in the city for three days? Where is he now? He was sent back to the village to grow old and die.’

Mpisi had then regretted telling Ntombazi about Mzila’s fate. Mzila should have known that no black person without a job is allowed to stay in an urban area for longer than seventy-two hours.

Then he had decided to change tack. He’d got up, walked over and stood in front of her. ‘Look, all I’m saying is that I can’t leave you on your own. You can’t give birth on your own.’

All Ntombazi had done was to snort with contempt. ‘Don’t worry about that. I have already called my sister Zonke in Ntunjambili to come. She will be here with me for a while. And I expect you to respect the dignity of our marriage by accepting my decision.’

She had stared at him, as if she were expecting something else or something more from him. As usual, Mpisi’s response was to withdraw into silence. After a brief hesitation, with a flicker of a warm smile, he’d conceded by nodding. Ntombazi had then turned to her boy.

‘Giyani, my baby, don’t forget to apply your snuff to your nose once it starts to bleed. Use it immediately if you see a tiny speck of blood. Don’t wait until you see the drops drip like you did the last time. And you must stop your nasty habit of picking snot from your nose and putting it in your mouth.’

Mpisi had watched his wife and realised her own vulnerabilities might have been fuelling her insistence that their new baby be born in Johannesburg. Mpisi first met Ntombazi as her tenant in Chiawelo, Soweto. When her first husband died in 1969, she had to arrange to be married to Mpisi immediately. The two were not lovers before, but she was forced to marry him to retain the house. The apartheid law denied widows the right of ownership. She could have lost the right to stay in the house if she did not marry within seventy-two hours. There was a moment, Mpisi knew, when she felt ultimate emptiness as she was nearly deported to Ntunjambili in Kranskop. The experience had made her aware that simply being black and a woman in her country was already a crime.

~~~

Niq Mhlongo is the City Editor. Follow him on Twitter.

~~~

About the book

When Mpisi Mpisani travels to the rural place of his birth, Gaza Village, for the burial of his mother and a visit to his first wife, he is highly aware that he should hurry back to Johannesburg. His second wife, waiting jealously in Soweto, will give birth any day now. Under apartheid law he might even be refused the right to return to the city if he stays away too long and loses his job. Giyani, his eight-year-old son, accompanies him.

But when Giyani disappears without a trace, Mpisi stays to search for him. Wracked with worry, he tries to ignore the villagers who blame magical sources for the boy’s disappearance. Meanwhile Mpisi’s city wife, Ntombazi, bears a boy with a birthmark that seems to be a sign …

The thread of mystery runs throughout Paradise in Gaza, weaved into an exploration of rural and city life at a time when movement between these spheres was highly controlled. Another exceptional novel by master storyteller Niq Mhlongo.

One thought on “[The JRB exclusive] ‘God withdrew from helping black people nearly thirty years ago’—Read an excerpt from Niq Mhlongo’s forthcoming novel, Paradise in Gaza”