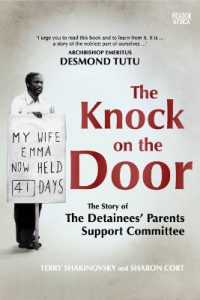

Pan Macmillan South Africa has shared an excerpt from The Knock on the Door: The Story of the Detainees’ Parents Support Committee, by Terry Shakinovsky and Sharon Cort.

The book tells the story of those who helped draw international attention to the atrocities being perpetuated against children – some as young as nine – by the apartheid state.

The book tells the story of those who helped draw international attention to the atrocities being perpetuated against children – some as young as nine – by the apartheid state.

The Knock on the Door will be launched on Tuesday, 27 February 2018.

Read the excerpt, take from Chapter 19 of the book:

A Woman’s Place is in The Struggle

‘We as women say: “Away with the state of emergency.” Unban the organisation of the people and give our leaders back to us.’

– June Mlangeni, FEDTRAW, Press Conference, 11 December 1987

Like so many South African women, Daphne Mashile faced additional burdens in detention because she was a mother. In late 1987, the DPSC began collating women’s personal stories of repression and detention for a publication, A Woman’s Place is in the Struggle, not Behind Bars. The DPSC then declared February 1988 as the month of Women and Detention. The organisation wanted to highlight the torment of women – those held in detention as well as the mothers, wives and sisters of prisoners. While the security police brutalised all detainees, women were subjected to particularly sadistic methods of torture and abuse of their womanhood.

Research for the publication revealed that sexual violence and humiliation were at the core of most interrogations of women. What women feared most was being raped. The security police deliberately used the threat of rape to force confessions out of female detainees. Many women and even teenage girls were, indeed, raped, and were too ashamed and fearful to report the offending policemen.

Endless accounts of insidious forms of sexual harassment and the conscience of the nation innuendo emerged, not all of which were documented in the publication. Women gave accounts of being kicked in the genitals, having their nipples electrocuted and being invasively touched while their hands were tied behind their backs.

Jennifer Schreiner was assigned an interrogator who had a reputation in Cape Town for torturing women. ‘He had stripped women naked. He had threatened Shahida Issel that if she didn’t co-operate he would go and rape her daughter. He had threatened to take me into the rural areas where nobody would know what he was going to do to me.’ It was part of a torturous game that emphasised the physical power men had over women.

Female jailers also used sexual humiliation as a tactic. At jails around South Africa, it was routine for women to be ordered to strip naked and to have their vaginas searched for contraband items. Connie Bapela recounts what happened after she and comrades smuggled matches into jail with which to stage a protest at their continued detention: ‘They took all of us to the punishment cell, the Kulukulu. Before you entered the cell, the female warders put their finger inside the vagina looking for matches, and the men were just watching.’

Women spoke about the humiliation of menstruating, particularly when they were denied sanitary pads and their bleeding was obvious. In some instances, ordinary policemen were more sympathetic, as Connie Bapela describes: ‘When I was menstruating … we tried by all means to create this relationship with the policemen – the black ones – so I gave them money to go and buy me some pads and they did. They would just say, “Eish … but why were you detained? You are so young. We don’t understand.” I tried to educate them but it was difficult in prison.’