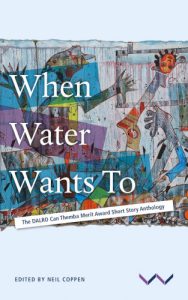

The JRB presents Dyondzo Kwinika’s DALRO Can Themba Merit Award-winning short story, excerpted from When Water Wants To.

When Water Wants To: The DALRO Can Themba Merit Award Short Story Anthology

Edited by Neil Coppen

Wits University Press

2025

Mr Duiker Sang the Blues

Dyondzo Kwinika

Morning had come. I wasn’t sure it would. Cold. Still. Heavy. I’d written him something. A poem. He hadn’t heard it. I needed him to.

I pulled on my black pants. White shirt. Black tie. Socks didn’t match. I didn’t care. Had to be there on time. I’d never been late. Not for him.

I reached for my scuffed shoes. The calendar hung on the wardrobe.

22 June.

The date sat on me.

It was Themba’s thirty-first.

I was going to fetch him. Same day I used to light candles for him. I’d been there when he was born. Germiston Hospital. Held him. Cried. Not from fear. From how innocent he looked. Nothing had touched him. I told him I’d give him what I never had. Protect him.

From the world. From myself. From everything.

For a while, I believed I had. Now, standing there, I knew I hadn’t.

Themba loved birthdays.

I remembered his fifth. Evelyn and I threw him a party. He danced barefoot to Brenda Fassie’s Nomakanjani, arms wide. Slipped between the shacks. No one saw him. Children loitered near the communal tap, waiting for water that came when it wanted. Not when it was needed. Wire cars swerved through garbage mounds. Sewage cut through dirt paths. Flies everywhere. Scuffles broke out. Pebbles scattered. Voices rose. Then diketo carried on, near the shack where we found him. He was under the table, cake on his face. Said he’d be famous one day. He was my boy. Their Brown Antelope.

I wished many things for him.

My hands trembled as I set the pot on the paraffin stove. I leaned closer to Marubini. She was snoring. Same rhythm. Calm and clumsy. Same childlike, twisted face. I chuckled. Forgot, for a second, that I wasn’t alone.

She arrived yesterday, after Soekie, my neighbour, who often rushed in. Half-drunk. We’d spent the afternoon at César’s, though I wasn’t drunk. I was numb all over.

‘Ousie, Evelyn called,’ she slurred. Pushed her glasses up her nose. They slid back down. ‘Your Themba’s landing at Oliver Tambo.’

I didn’t need to hear anything.

‘Ka nako mang?’

‘Before nine.’

Her doek slipped off. She couldn’t remember the airline. I did. Swiss Air Lines. He always took it.

I was on the bed, lost in thoughts of him. Of everything that had brought us here. Then I heard it.

Three knocks.

‘Ko-ko-ko, Pa.’

I paced to the door. Chest tight. I wasn’t ready, I opened it anyway.

Maru stood there. Bag in hand. Her face was blank, except for tired eyes. She wasn’t visiting. She was coming home to me. For good.

I saw the bandage on her wrist.

I remembered the afternoon at the SABC in Auckland Park. She was on set for When Rain Clouds Gather. Bessie Head’s novel adapted for television. Paulina Sebeso wasn’t a part she played. It swallowed her.

‘I use them.’ She didn’t look up. ‘I’m not addicted, Pa.’

Her eyes shifted to the door.

‘When did they become important?’ I asked.

She didn’t answer, fingers tapping against the chair.

‘When people stopped seeing me as Maru. Only Makhaya’s wife from TV,’ she said. ‘When things broke with Themba … that’s not for you to know.’

I said nothing.

It wasn’t about Eve. Or Themba. Or her work. It was me. I saw it. Compared her to him. Always had.

The candle sputtered. Shadows stretched across the table. Some of Themba’s vinyls lay there. A Brief History of Marubini among them. The cover worn thin. Title fading. He was Maru’s age then. Younger, even. I remembered that night at Untitled Basement in Braamfontein. He’d finished his set. Picked up the record, looked at it, then handed me a signed copy.

‘Why’d you name my sister after this?’ he asked.

I didn’t answer. He already knew.

‘I read up on it,’ he said. ‘I know what Marubini means. A home no one talks about.’

He smiled, not waiting for a reply.

‘This’ll remind you of what you tried to leave behind. What’s waiting for you.’

I thought he meant something else. Not Maru.

She was auditioning then. Told to smile. Sometimes pushed further. She didn’t. Never talked about it.

I stopped seeing her.

‘Maru: A Pula’, a tune from the album, won the 2015 Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Jazz. Eve, Maru and I drove to Themba’s apartment in Kikuyu Waterfall. Third floor, Block D. I bought a red papsak wine. He liked it, even when he could afford better. He poured me Three Ships on the rocks. Said it was for old time’s sake. We stood on the balcony watching fireworks over Waterfall City.

He asked if I saw Maru the way I saw him.

I think she heard. Or saw. Either way, she dropped a plate in the kitchen. Glass shattered. She said nothing. Picked up her phone. No shoes. She left.

I told him I’d fix things with her. Said she’d get over it. She was moody. Told myself it was timing. She knew I loved her.

It was the last time I saw her.

‘I’m sorry, Papa,’ she whispered. ‘I was broken. Lost. Hopeless. I want to come home. Rebuild what I can hold on to.’

‘It’s okay.’

I wasn’t sure if I meant it. It was what we needed to hear.

I lifted her bag. Then I saw him. A laaitie. Four or five. Silent. Half behind her. I hadn’t known. She’d had a child. Raised him. Without me.

What father didn’t know he had a grandson?

I had no one to blame. I raised snakes. It was the truth.

I wondered if she’d told Themba. Called or written to tell him he had a nephew. I didn’t know what that would’ve done to him.

I wanted to ask how she found her way back here. Then I remembered. This was home. The place we grew up. The place I tried to raise them. The place we all learnt how to survive, no matter what.

She hurried in. I put her luggage on the bed. Didn’t know where to start. Her eyes searched mine, looking for something. Answers. Solace. I had nothing, only silence.

Sandile darted around the shack, laughing. Oblivious to the moment, smiled up at me. ‘Is he my mkhu… mkhulu?’

Maru nodded.

The two-roomed shack held the three of us. Once, it held four.

I stepped outside after drying the basin. The world was silent. Then dogs barked, goats bleated and pigs grunted far off. Rats scurried and cats meowed as they chased them. Frogs rasped in the muck behind the toilets. The first taxi rattled over the dirt road. I caught Umanji’s Moloi drifting through the windows.

The place slipped past me. I’d spent too much time thinking only of myself.

My beret was heavier. I folded the poem enough for my chest pocket. My hand trembled, and it slipped out. I picked it up, hoping no one saw. Dug a crumpled joint from my shirt pocket. Lit it. Took one or two puffs. The smoke was bitter, stuck in my lungs. I spat it out. Pot smoke hung in the air. I flicked the stompie onto the ground. Stomped it flat.

The taxi hooted as it faded down the road. For a moment, we were back there. Themba and me riding in the back of that sixteen-seater. June. Winter. When boys became men.

The taxi dropped us at the rank down Oranjehof. We took another, which let us off near Wanderers. I caught a flicker of something in Themba’s eyes when he saw the hobos wrapped in plastic and tattered blankets trying to keep warm. He said nothing. Trusted me. His hand stayed in mine.

We pushed through the crowded streets until the Park Station sign came into sight. The ceiling arched above us. People were everywhere. Hawkers shouted. Wares. Beanies, socks, scarves. The Star, Daily Sun, Sowetan and Laduma. Chargers and cigarettes. Near the main concourse, pantsulas stomped and danced. Spectators roared. Coins clattered on the floor.

We moved past the turnstiles and shops to the corridor after Debonairs. Dr Cajee’s office at the corner, ground floor of the old concourse. A worn sign hung above the door. The buzzer barely worked.

Themba looked up at me, eyes wide.

‘Why are we here?’

I didn’t answer. Told him this was his passage. Something I’d gone through. Something that meant he belonged.

I couldn’t explain. Not to him. Not to anyone.

My father wasn’t a man. Ma said he was with Samora, fighting for FRELIMO. She prayed he’d return after the war. I never understood. His absence shaped everything.

Since then, I ran. From my country. From myself. From the man I was supposed to be. I didn’t want my boy to feel it. He did. Watched me when I wasn’t looking. I turned away before it became something.

Cajee smiled and pulled on his gloves, the latex snapping tight. I lifted Themba onto the table. Told him I was there. He could scream if he needed to. He didn’t. Stared at the harsh lights while the surgeon did what he had to do. I sat on a chair, flipping through a worn copy of Soccer Laduma.

When it was done, he wrapped Themba in bandages. Gave him a sweet. Said he was a good boy. We headed home. Eve and Maru were by the paraffin stove, stirring a pot of putu. The oily smell of boerewors mixed with paraffin smoke hung in the air. On the table sat a bowl of fresh tomatoes, sliced and ready for the stew.

We sat, laughed and ate.

I helped Themba onto the sponge mattress, tucking the threadbare blankets around him. The pain kept him restless, he didn’t complain. When sleep came, I stayed by the bed. Didn’t mean to. My hands trembled. Throat tightened. I sat there long after the house quietened. Then I cried. Not for what I lacked, but for the man I was trying to be. For the son I’d helped become a man.

I glanced at my watch. Quarter to five. I’d told César I’d be outside his tuck shop before six. Three sections from mine. We had to be at Arrivals. Terminal A. Eight o’clock. I wasn’t sure if Eve was going to drive from Sandton to pick me up. Things hadn’t ended well between us. She said she needed stability. Married a high-profile lawyer. Sat on the board of Daggafontein Children’s Home. I always thought there was something else to it. I never asked. She was the woman people listened to. Coconut, for sure.

I remembered meeting her, outside my tent, where I cut hair. By the bus stop. She was barely eighteen. Pregnant. Tossed out by her family. Pretty, not obviously. Lucky Dube played on a battery-powered radio. The horrible sound filled the space. She said she needed a new start. Asked for a chiskop. Didn’t flinch when I cut close to the scalp. Paid me five bob or a rand. Said I looked tired. I didn’t sleep that night. In her, I found something close to home. A country I could belong to. Five years ago, I called her. Begged her to answer. I had to tell her our son was leaving for Zürich. Not for his Duiker Ducks When Startled tour. Not for leisure. For something else. Something only he understood. She never picked up.

Later, she said, ‘He looked exhausted. Lost. He was unravelling.’ She lit a cigarette, drew in hard, then added, ‘I tried to stop him. I even asked Josh to reason with him. He closed his eyes and looked through me.’

I told her I didn’t feel anything for him. Thought he was selfish. I was too. I didn’t know if I pushed him or if he was already halfway gone.

Eve confronted me yesterday about the call we both received from Josh.

‘Sir … I’ll be bringing him home.’ His voice broke. I missed the rest. Glass hit the wall, then a scream.

My body moved before my mind caught up. One moment I was on the phone. Next, I was at Soekie’s door, falling into her arms. Everything hit at once.

The call took me back to that Christmas. Eve phoned. Said Themba missed a couple of gigs. Told me to search for him. I ran down the streets of Yeoville. Through Hillbrow. Past Bertrams. I found him at Domus Peccati.

High. Eyes dead.

He didn’t recognise me. Not at first.

‘I’m fine, Papa,’ he said.

He wasn’t.

He didn’t know where the light had gone. It had gone long before.

‘I want to fly, Papa,’ he said. ‘Leave all this behind. Slip through the cracks in the world. Float away. Wherever the sky takes me. Until I’m nothing.’

I heard it for what it was. It wasn’t freedom he wanted. It was escape.

Eve stood at the door, arms folded. Dim glasses caught the light, black doek tight around her head, shawl over her shoulders. I was a mess, unkempt, eyes hollow, had not eaten or slept since the call.

She stared at me. Said nothing.

‘What’s wrong, Eve?’

She shook her head and stepped inside. ‘The call from Josh,’ she said. ‘You knew about it, didn’t you, Ebenezer?’

I said nothing.

Her voice dropped. ‘So this is how you were going to do it? Bring Themba home without telling me? Without asking?’

She paused. The edge softened. It didn’t disappear. ‘Ag man, sies.’

‘The same boy you never wanted anyway.’ I let the words hang. ‘Eve – ’

Her hand rose. The slap was light. Desperate, not angry. My cheek burnt.

‘He was mine,’ she said, trembling. ‘Not yours.’

It hurt. I didn’t move.

Soekie and some neighbours stepped in. Told us to stop. Said it wasn’t about us. Said it was about him.

Themba.

I looked at her again. We were older now, tired. I saw the woman I knew. The one I lost.

Without thinking, I reached out. She didn’t pull away.

‘I wish I’d told you’, I said, looking down, ‘how much you mean to me. How different my life is because of you. Because of the children.’

She didn’t answer. Only stared.

‘I’ll make arrangements,’ she said. ‘Ke tla o letsetsa when everything’s ready.’

I didn’t know if she would. I hoped she would.

I didn’t realise how fast I’d walked from my shack to the shacks at the edge of Section B. Stopped near Soekie’s yard. Her gate hung crooked, held up by a bent coat hanger. The rosemary bush at the corner reeked of dog piss. The grass near her stoep was gone. Hard ground now. Scattered with bottle caps, broken glass, burnt-out cigarette butts and bones.

She used to work the Brakpan route before the ulcers took her legs. Now she sold atchar and chakalaka in old jars. Loose draws. Let people charge phones off her car battery. Kept her curtains closed most days.

I leaned on her wire fence, palms pressed flat, breathing through my mouth.

The dogs barked before I saw them.

Four of them chased two tsotsis down the alley behind her place. The thugs clutched bits of scrap. I saw rusted copper rods, part of a basin stand, even brake parts. Stolen. The dogs barked. The boys jumped the ditch and ran for the wetlands.

I knew them. The Jealouz Boyz of Daggafontein. I’d seen them near the scrapyard by the Blesbokspruit. Faces half-covered. Hands never empty. Always watching. Waiting.

Themba was that way now. Something watched me from the edge. A shadow I couldn’t reach. I didn’t understand how he’d left. He was running. From something. From me. From himself. From here.

It wasn’t always like that between us. Things changed. Slowly at first. Then all at once.

He was meant to come home for Easter. He arrived late. Stiff in the wheelchair. Pale. Hands trembling on the armrests. Said he’d been mugged.

I asked why he didn’t call me. Or Mme. We could’ve met him at the stop. He shrugged. Said Wendy dropped him close by.

‘Themba,’ I asked. ‘Who did this?’

‘I … I don’t know, Pa.’

I left my beer half open on the table. Grabbed his arm and wheeled him out. He tried to speak. I didn’t let him. Held the lamp. The glow swung across the ground as we moved.

We cut through the settlement. Past the rows of mikhukhu. Torn laundry lines. Kids out, playing mokoko. Shouting. Dogs barking near the pit latrine. Eve called after us from the stoep. I didn’t stop.

The ground was soft ground near the stream, full of muck and the stink of stagnant water. The lamp flickered in the wind. We found them where I knew they’d be. Huddled under the gum trees near the reeds. One was drinking from a papsak, the others passing a bottelkop between them. A radio sat on the tyre beside them, blaring Mandoza’s Nkalakatha. They were laughing. Swaying to the beat. Shoulders bouncing.

They saw me coming. Didn’t move.

I moered the first one in the mouth. His teeth snapped against my knuckles. Another tried to grab me. I kicked him in the gut. They scattered. One pulled an Okapi knife. I didn’t back off. Swung again.

I wanted them to feel the weight Themba carried.

He stayed behind. Eyes wide. Terrified. Not of the thugs. Of me.

‘Papa… please don’t,’ he said, voice shaking, trying to wheel himself forward. ‘Stop, please.’

The tsotsis ran off into the dark.

I picked up his practice journal. Pages torn. Some creased. Ink smeared. He said nothing. Looked at me. Silence filled the space.

For years, I told him what it meant to be a man. We didn’t raise hands. Strength was in holding back, not in throwing.

Then I showed him something else. Blood on my knuckle. I wiped it on my trousers. Some of it wasn’t mine.

He didn’t flinch. Coiled back. Arms folded. Shoulders drawn in. I was something he’d seen before. Something he never wanted to be.

I didn’t speak. Walked.

He followed.

We passed Eve again. She didn’t speak either. Her shawl tight around her arms. Face blank.

The night waited. It knew what had happened.

It was half past five when I passed the laundry flapping against the fence near the park in Section C. Themba said it was his favourite section. Out of the four. Said it was quiet. He liked the merry-go-round. Rusted. Off-centre. Watched it spin. The April before he left, he’d asked me to drive him there. After what happened with Wendy. Backstage. Cape Town Jazz Festival.

We sat on the cement block near the jungle gym. Watched the birds in the trees. Hadedas, mostly. The sunset didn’t last. He opened a Black Label. Took a long sip. Dug into his wallet. Pulled out crisp notes.

‘Here,’ he said. ‘I want to thank you. While we’re both here.’

‘What for?’ I frowned. ‘There’s no need. Ha o nkolote letho.’

I took a long sip. Then reached out. Rubbed his back.

‘If you think you do, then let it be to live your truth.’

Then I saw it. Guilt. He knew. I hijacked bakkies. Robbed delivery vans. Looted spaza shops during protests. Stripped copper from broken streetlights. I needed machankura. Had to get him his first keyboard. A second-hand Casio.

I remembered taking him to Kippies. Newtown. He must’ve been ten or eleven. The look on his face when he saw that grand piano in the corner. Something clicked. He belonged there.

Some nights we stayed up till one, two, three in the morning. I’d sit on the bed. He’d play a chord, turn around, ask if it sounded like church or stokvel. Then play it again. Faster. Slower. Laughing. I said nothing. Let him play.

‘Don’t worry, Papa,’ he used to say. ‘One day I’ll take care of you.’ He’d smile then. ‘O tla bona. Get you a house in Selcourt. A gold Casio watch. A Cressida. A trumpet.’

He remembered things I’d forgotten. The way I used to talk about that car when I was drunk. He saw something in me. Something I didn’t see.

The house he said he’d buy me never happened.

I pictured it sometimes. Beige curtains. A veranda. Two chairs. Facing the street.

The Cressida. I never drove it.

The trumpet.

Some nights, I thought I heard it. A note or two. Then silence.

I told myself it wasn’t finished. There was a song left in him.

We finished the case. Smoked through a full packet of Stuyvesant. He told me things. About contracts. Unpaid royalties. People he’d loved. People he’d hurt. The things he’d seen, the things that followed him. He called them ogres. Shadows with teeth.

Said Wendy caught him and Josh. It spiralled. She smashed his piano. Smashed the windscreen of his Jetta. Screamed. Dragged him by his dreadlocks. Some tore out. He pulled her down. From his wheelchair. Forced her to the ground. Ripped out her braids. Hit her. She didn’t get up.

She told the Daily Sun: ‘Brown Antelope didn’t love me. He used me. I did the bookings, the management, everything. He lied. Bonked around. Snorted coke with washed-up kwaito boys in Melville. Sometimes Hillbrow. Broke me. Slowly. Said the music came from pain. Chaos. It worsened.’

She didn’t report it. Afraid of the backlash. He was arrested anyway. Assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. He counter-charged. Damage to property. Assault. They dropped them all. Nobody wanted the drama.

He wasn’t perfect. Neither was I.

He saw what I did to Eve. The shouting. The bruises. The nights I stayed out. Kids don’t forget. Even when they try. The damage stays. Changes shape. Follows them. What did I think would happen?

On the way back from Section C, we talked longer than I thought we would. Old shows. Gigs that didn’t work out. Politics. He laughed. A sound I hadn’t heard in years.

Then Diaraby Nene by Oumou Sangaré started playing. He turned it up. We bounced our heads to the beat. As I tapped the steering wheel, trying to catch the rhythm like van toeka af, I remembered him telling me about places he’d been. The sounds he’d picked up along the way.

We drove past a boy splashing himself with a bucket. Two drunk uncles bickered over morabaraba. A haggard woman scrubbing blood off her stoep. Baby tied to her back. Not far off, mealies roasted over a charcoal stove. The smoke filled the air.

When we got home, I stepped out first. Pulled out his wheelchair from the boot, unfolded it. Placed it on the back seat. Close enough for him to reach. Then helped him slide across to the driver’s seat.

He sat still for a moment, then looked at me.

‘Okay, Papa. I love you. Forgive you. For everything.’

I said nothing. I nodded, gripping the car roof to steady my shaking hands.

He reached through the open window, fingers brushing the door handle, then stopped.

‘Let’s have breakfast soon. Mugg & Bean. Before I leave.’

I stepped back.

He raised a hand.

‘I want you to meet Josh. There’s something I need to say.’

He shifted the car, pulled off slowly. Then dust rose behind him, swirling in the fading light.

Five minutes from Césabantu Cash & Carry. I wondered if Maru was done. I’d told her César and I would wait outside the shack before half past six. I didn’t want the traffic to hold us up.

I thought about last night. I’d stepped out to light a joint. Smoke rose, curled in the air. I walked to the pit toilet. I needed to pee. Needed a moment away from everything.

By the time I arrived, I became lightheaded. Sank down, back against the door. The stink clung to the air; I barely noticed it. My body shivered. Then came the tears. I curled into the dirt and let them fall.

Rodents scurried over my legs. My chest jumped. I didn’t scream. Didn’t move. My fear sat there.

I thought about ending it. Not from courage. Something else. Letting go.

The zol had burnt out somewhere behind me. Smoke hung thick. I wanted something to hold on to. There was nothing.

Then I heard footsteps. Reached for my Okapi knife. I’d forgotten it.

The steps were slow. Familiar. Maru.

I tried to stand. Legs buckled.

She didn’t speak at first. Placed her hands on my head.

‘Ho lokile, Ntate.’

I was kneeling. Mud on my knees. Tears on my face. Her thumbs moved along my scalp. I was a child again.

She didn’t pray aloud. Her hands did.

I remembered her prayers. For Themba. For Eve. Always soft. She knew words couldn’t reach them.

A car passed in the dark. The engine dragged.

Headlights swept across the shacks. Ho Lokile played low.

I thought of Themba. What I never told him. What I never asked.

I didn’t ask Maru to forgive me. I didn’t ask for anything. I let her hold me.

Later, she said, ‘We fetch him tomorrow.’

I nodded. The silence was enough.

Six on the dot. César was already waiting by his Toyota bakkie. Engine running. He ran things around here. The rent he extorted left us bleeding. He’d turned into a comrades. Fat off our backs, rotten, dead eyed. I’d told him about my boy. He said he knew I’d do the same for him.

He held something in his hand. I looked, then looked again.

‘Ndithenge umlahlankosi, mfokabawo,’ he drew on his Stuyvesant, smoke curling around his words. ‘Alwehlanga lungehlanga, Duiker. It’ll pass, bra. Hold on.’

He said it the way men did. It was all there was to say.

Eve suggested he get umlahlankosi from the herbalist in town. The buffalo thorn. For the spirit to find its way home. I nodded. Didn’t say a word.

I kicked a trash can. Thought about the last time I saw Themba. Blamed myself for how he’d left. For what his country wouldn’t let him do. Said we had a right to life, not the right to leave. I kept going over our conversation. Mugg & Bean. The morning was cold. Not the weather kind, the kind that stayed with me. He meant to leave me with it.

I’d expected Josh to be younger. Themba’s age. He wasn’t. He was older, tall, thin, scruffy. Hippie-ish. Said he lectured drama at Wits. I saw nothing of that in him. He looked at my son like something broken he wanted to shape for himself. Themba didn’t pull away.

Josh said nothing. Tapped Themba’s shoulder. Reached into his pocket. Pulled out a cloth. When he saw the tears starting to fall, he handed it over.

Themba’s fingers closed around the cloth. Then he let it slip back into Josh’s hand. He looked at me. Tried to speak. Nothing came out.

We sat by the window. No one said much. I glanced around, trying not to look at him. A painting of a baobab hung on the wall beside us. Branches stretched across a sunset. I stared at it. Hoping for a sign.

Then he said it. ‘I’m moving to Switzerland.’

I blinked. ‘For what?’

‘For … the ending.’

‘O reng?’ I frowned. Shook my head. ‘You think you can leave?’

His face was puffy. Eyes dull. Shoulders low. Hands folded on the table, fingers twitching, unsure where to rest.

‘I’m on the list,’ he said. ‘The pain … it’ll stop there. It’s legal. Takes time.’

I leaned back. Tried to understand.

‘You’re twenty-six. This isn’t real.’

He looked down. Not at me. At the table.

‘It’s not the wheelchair,’ he said, voice low. ‘Not even the pain. I … can’t anymore. I don’t sleep. Breathe. It’s like … there’s a war inside me. Nobody sees it. Not you. Not Mme. Not Maru. Not even Josh.’

‘When did this start?’

‘Wits. Second year.’ He closed his eyes and, for a second, I thought he’d cry; he didn’t. ‘I ended up at Charlotte Maxeke. Slit my arm. They said it’s something I’ll live with. Meds. Therapy. The ups. The crashes. I’d feel alive. Then nothing.’

I wanted to ask him why not hold on, fight, carry the pain, let it win.

‘You don’t have to,’ I begged. ‘We … we can fix this. Slaughter – ’

I didn’t finish. I think he heard it.

‘You don’t get it,’ he said. ‘You never did.’

I wanted to say something. Anything. Nothing came out. I reached for my coffee. Cold. My stomach churned. I wiped sweat off my hands with my pants.

‘I’m not doing this for attention, Pa,’ Themba didn’t raise his voice. ‘I’ve tried. Ha ke sa khona.’

For a moment, the café carried on. Clinking cups. Murmur of voices. I barely heard. He didn’t look at me the way he used to. The love that once held us had slipped and left only silence.

I reached for his hand. Cold. He didn’t pull away; it felt distant. I squeezed harder than I meant to. He winced. Didn’t let go.

I held on. Like I could stop it. Stop time. Stop death. Stop the leaving.

‘If you do this,’ I said, wiping my nose, ‘then I’m gone, too.’

He smiled faintly, worn down. Bleak eyes.

‘I know, Dad.’

It was noon. I didn’t realise we were crying until Themba asked Josh to wheel him away.

Josh stood, pulled his sleeve over his hand and wiped Themba’s mouth. Then tucked the cloth back in his pocket. Didn’t look at me. Took the handles of the wheelchair and turned it.

‘If it takes long,’ I said slowly, ‘if things change … you can always come home.’

Themba nodded. Then said, ‘That’s the part I’m scared of.’

Outside the Chicken Licken near the Rosebank Gautrain Station, I asked Josh to stop.

Themba looked up.

I knelt in front of him. Knees cracked. People passed. No one looked.

I put my hands on his knees. He leaned forward. Our foreheads touched. My eyes stung. I pulled him in.

His arms were thin. I felt the bones. I held him. Tight.

Josh knelt beside us. Rested his hand on Themba’s back. No words. The three of us. In that crowd, in that smell of chicken and petrol.

Then it was over.

I stood. Cleared my throat. Took a step back.

Josh wiped Themba’s cheek, then gripped the wheelchair handles. Slowly, he pushed the chair down the narrow ramp beside the stairs into the underground concourse. Wheels scraped the concrete. The chair jerked now and then. Josh leaned in as the slope pulled Themba away from me.

I followed. Not fast. Not slow.

The crowd moved. Bags swung. Phones to faces. Turnstiles clicked. Fluorescent light. The speaker’s voice, cutting through.

I kept walking. Eyes searching.

I saw Themba again. He wasn’t waiting for me. He saw me. Once.

Josh guided him through the wide gate, then to the lift.

Themba didn’t move his face. The door closed.

I stayed where I was. His warmth on my shirt. As if he was there. For a second, I let myself believe he hadn’t left. I turned. Moved back through the crowd. Up the stairs. Into the air. I lit a loose draw. Took a puff. He was gone.

The winter sun was out, low and cold. César stopped beside my shack. He hooted. Maru stepped out, wrapped in black, doek on her head, Basotho blanket over her shoulders. Her eyes were tired behind lenses that didn’t hide much.

Maru and Sandile climbed into the front with César. She managed a half-smile. It didn’t reach her eyes.

I stayed in the back. Hands clenched against my knees. Watching them. I didn’t trust him. Not with her.

We drove back to Soekie’s. I knocked. She opened. Looked at me, then at Sandile. I asked her to take him. She nodded and stepped aside.

The road was rough. Air full of dust and petrol. My heart stayed tight.

I thought of Themba. His face. His body. His absence.

Would I recognise him?

I closed my eyes. Fear stayed.

Behind the bakkie window, I heard Zahara again. Loliwe.

I glanced at my Casio. Themba’s gift for my fortieth. He’d smiled when he gave it to me. Said life began then.

I wondered if he believed that.

Tick. Tick. Tick.

I pulled my knees up to my chest.

César took the R24 turn-off. The airport sign blinked.

The sky was clear. The moment close. I hadn’t said what mattered.

~~~

- Dyondzo Kwinika is a South African writer based in Orlando West, Soweto. He is the inaugural winner of the DALRO Can Themba Merit Award. His work explores identity, mental health and generational trauma, examining how history and culture shape the ways we love, grieve and change.

~~~

About the award

The Dramatic, Artistic and Literary Organisation (DALRO), together with Wits University Press and The Market Theatre, in partnership with the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Creative Arts, presented in 2025 the inaugural DALRO Can Themba Merit Award.

This prestigious competition aims to celebrate the legacy of one of South Africa’s literary giants, Can Themba, while at the same time creating a platform for emerging short story authors. Can Themba’s writing remains a powerful force in South African literature, known for its bold storytelling and keen social commentary. The DALRO Can Themba Merit Award seeks to uphold his legacy by bridging literature and the dramatic arts, offering an innovative extension of storytelling into theatre.

The DALRO Can Themba Merit Award will run on a two-year developmental cycle. 2025 focused on the literary component, mentorship, story refinement and publication, and 2026 will focus on the dramatic adaptation of the award-winning short story into a stage play, premiering at the legendary Market Theatre.

Publisher information

In celebration of Can Themba’s legacy, When Water Wants To brings together the ten winners of the literary competition, the DALRO Can Themba Merit Award.

During embalming an arm jerks and strikes a mortician, leaving him unmoored. A pastor’s wife encounters a young congregant in her kitchen wearing her apron and preparing breakfast. A man’s attempt to make sense of why a tornado picked him up leads to a showdown with a cult leader. A daydreaming, gawky kid is appointed guardian of a watermelon that the ocean could snatch away. Love comes slowly, like water heating over a low fire or extra sugar being stirred into tea. In another story, the love of a father cannot save his musician son. A young woman living in a recognisable future contemplates the end of memory as her body transforms into the silver promise of a carapace. Another young woman feels she should be smiling but nothing stirs in her when her father wakes from death after 15 minutes. Battling portentous pre-dawn heat and still air, a bystander abandons removing caterpillars from a Ficus because the idea of touching them makes her squeamish. Elsewhere in the suburbs, in a fixer-upper from hell, crickets screech and squeal, their ringing like that of a demented alarm clock.

Celebrating the legacy of master storyteller Can Themba, When Water Wants To provokes, inspires, challenges and entertains with bold storytelling and keen social commentary. The stories range from the deeply personal to the wildly allegorical, playing with genre conventions and inhabiting a multitude of perspectives and unruly voices. These exciting new authors confirm the pre-eminence of the short story, and its oral antecedents, by delving into the national psyche in the conversations they have, the connections they make, and the themes, concerns and water-soaked imagery they share.

The story is nicely weaved. Well crafted and indeed it is a powerful story. May the muses always adore you.

Mr. Duiker sang the blues: author- Dyondzo kwinika. The story is short yet compressed with lot of information, which raises lots of questions in mind such as, who is Mr. Duiker? Is he Themba’s father or loved by him? What kind of music Themba Played? Which country he flighted to? Was it Switzerland or another country? Will Themba return walking or still wheel chair bound and so on?

Brilliant. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this piece. The intricacy. The textures. The layers.