This is the ninth in a series of long-form interviews by Patron Makhosazana Xaba to be hosted on The JRB, which focus on contemporary collections by Black women and non-binary poets. The others can be read here: Maneo Refiloe Mohale, Katleho Kano Shoro, Sarah Lubala, vangile gantsho, danai mupotsa, Busisiwe Mahlangu, Tariro Ndoro and Saaleha Idrees Bamjee.

In opening up a space for wide-ranging, erudite and graceful conversations, Xaba aims to correct the misdeeds of the past by engaging black women and non-binary poets seriously on their ideas and on their work.

Two previous long-form interviews, with Mthunzikazi A Mbungwana on her isiXhosa volume Unam Wena, and with Athambile Masola on her debut collection Ilifa, were published in New Coin in 2022.

~

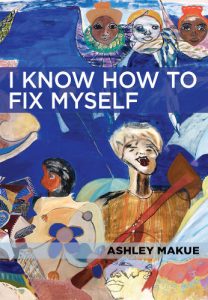

Makhosazana Xaba (MX): I first happened upon your poetry through the debut collection i know how to fix myself, which was published in April 2017 by the African Poetry Book Fund as part of their New-Generation African Poets chapbook box set. Please share the nine-year biography of this book.

Thabile Makue (TM): Over the past nine years, I’ve grown a great deal—both as a writer and in my perspective. And because of that, the world of i know how to fix myself has aged too. There are edits I long to make. But there are also moments that feel frozen in time.

It was written before I left Cape Town, before my divorce, before I became unsure of my voice—and then, eventually, more sure of it. Since then, I’ve lost two of my subjects: my grandmothers. My mother and aunt have grown new lines in their faces. My sister became a teenager. I became more alone and more embraced at once.

Still, the answer is the same—the ‘how’ of fixing myself. Though now, it has been tried and tested. The chapbook is still my great pride.

MX: The chapbook box set is such a unique idea; one I welcomed with excitement and feel proud to own. What did it mean for you, to be selected and published by the prestigious African Poetry Book Fund and Akashic Books? Do you know the work of the other ten poets, besides Vuyelwa Maluleke?

TM: Being included in the box set was an incredible honour. The collection, Nne, is so rich and dynamic. It included two of my favorite writers: Mary-Alice Daniel, whom I recently shared a stage with at the 2025 Calabash Literary Festival in Jamaica, and Chekwube Danladi, who hosted a queer offsite reading at this year’s AWP conference in Los Angeles. Both are great writers whose work inspires me.

MX: Thank you for introducing me to those two poets. You were a finalist for the 2018 Sillerman Poetry Book Prize. How did that feel and what did it mean to you? Please respond to these two questions with a poem.

TM: Being a finalist for the Sillerman prize felt like a great feat. There is a softness and quietness in my work that felt dismissed in many spaces. I entered Sillerman after spending a long time trying to find a publisher in South Africa, and being told often that I needed to write differently—‘more political’. Of course, I knew they misunderstood the world of my poetry. The romance, sexuality and emotional landscapes of my mother and her mother are deeply political experiences. But they are also spiritual experiences. Being recognised by Sillerman, especially in the same year that another of my favourite writers, Safia Elhillo, won, felt like a balm for all that rejection. It meant that somewhere, my work was understood.

I’m currently working on a new collection, and I don’t have any unpublished pieces that aren’t already intended for the book. Because of that, I wasn’t able to offer new poems for this interview.

Instead, I’ve shared a few selected portraits.

MX: Thank you for these portraits. Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, the novelist, poet and scholar, wrote a preface to your collection that she titled ‘Praise and Fire’. How did that process work?

TM: First of all, I am a great fan of Honorée Fanonne Jeffers and was honoured that she graciously agreed to write the preface. She was chosen by my publisher, and what a perfect fit. Her preface situated my work in an international context, giving it new lineages and resonances.

MX: I was intrigued by Jeffers’s interpretation of your use of the lowercase:

Each poem is written in lowercase, which may simply be a stylistic choice, […] But when viewed on the page, the eschewing of capital letters appears metaphorical, an indication that the poems’ main ‘character’ continues to evolve.

Three years later in your second collection, ‘mamaseko, you continued to use the lowercase. What lies behind this choice?

TM: I write poetry in lowercase and without punctuation because it gives me a new door into the language. English is a language I acquired. To make it mine, I had to collapse its rules. I had to mould and shape it—to make new words and new sounds. To translate. To imbue it with my own language and its music. To add prayer and song. I also think letters are more beautiful in lowercase. Like little seedlings, ever at the edge of blooming. As Honorée Fanonne Jeffers says, in this form, they have the potential for evolution.

MX: Jeffers references ‘Elain Vera’, a writer I was unaware of and whom I googled while suspecting I wouldn’t find her. And then I double-checked my five copies of Yvonne Vera’s books to see if she uses this second name. It was then clear to me that this: ‘And many times , emotional—painful—longings get passed down through female heredity in what South African writer Elain Vera has called “writing near the bone”’, was an error. Jeffreys was referring to Yvonne Vera, the Zimbabwean writer. Are you familiar with Vera’s work, in particular the referenced ‘writing near the bone’?

TM: I wasn’t familiar with Yvonne Vera’s work before, but I read ‘Writing Near the Bone’ and was completely taken by it. It gave me yet another context for my work. It made it true again that writing is a spiritual doing. ‘A force entirely organic and sensual, one of great power and daily importance.’ I still find it impossible to answer, with certainty and detail, about my process of writing. It is something entirely organic. My closest suspicion is that it is a way to channel. To know things before you know them. I’m not of the school, especially in poetry writing, that separates the narrator or speaker from the writer. I like the idea of a writer who is not only cerebral and emotional, but also physical—embodied, bleeding, prone to death. It makes the bone important, true. It also makes the bone spiritual. The body is the channel—the seer, the writer. I kept a lot of treasures from my discovery of Yvonne Vera’s work.

MX: Jeffers calls i know how to fix myself a ‘lyric biography’. The titular and opening poem feels like a comforting warning to the reader. Those last five words say a lot; I felt like I was told to put on my seatbelt:

my great-great-grandfather begets my great-grandmother. my great grandfather begets my grandmother. my grandfather begets my mother.

my father begets a ghost.

TM: Yes. I am a writer and lover of lyrics. I was conflicted while writing ‘mamaseko. I wanted to write a book of lyrics, but I also wanted to give the reader texture and diversity. Now, as I work on my next collection, I am surer. This is another thing Yvonne Vera gave me. To no longer be contracted by my reader to any theme or form. I am writing a book of lyrics. A new lyric biography. This is my form because this is the form of hymns and scripture, and my grandmother’s warnings and lamentations.

MX: Oh, this is exciting news, I cannot wait to read a lyric biography! It’s been eight years since i know how to fix myself was released. Please write a poem that captures your understanding of how the readers, reviewers, poets and people in your life responded to your debut collection.

TM: See above.

MX: There are fourteen powerful poems in i know how to fix myself. In the second, ‘seasons of alone’, you use three similes in the opening stanza that suggest chaos, struggle and pain.

the winter scatters the strands

of your hair like cluttered echoes

like chasing your father uphill

like a purse as unkempt as your mother’s heart

And, as I read the second stanza, hoping things might get better, I instead felt despair. Your ability to elicit strong emotions through simple words is impressive. Does this come naturally, or do you work hard at it?

your mother was a spring day when she had you

and then the dust

and the wind

and the things that are torn away

TM: My general disposition is one of suspicion—not paranoia, but curiosity. I always sense that there is more to things. Language itself is complicated. In ‘mamaseko, I was experimenting with a closed vocabulary. A dialect for my narrative world. I was curious about making many meanings of the same words and sounds. I was conflicted in this as well, but I am much more convinced now, in the process of my next collection. I have grown as a writer, so even though I can’t detail my writing process, I am privy to it.

MX: ‘mom’s on fire’ is an impactful poem, infused with unexpected humour as if to douse the raging fire. You manage to say so much in these two lines ‘she prays that her clitoris rots / and that his penis disappears’. This is a powerful metaphor. What led to this choice?

TM: I was thinking about the nature or way of desire. The biology of it, too. Despite our many differences, my mother, grandmother, and I are drawn to the same person: bad mood, cruel, unavailable. Though the generations and even genders are different, the person is the same. In this poem, I was asking if the body is the reason for this. I now know that the answer is yes and no.

MX: It’s the longest poem in the chapbook, with 23 stanzas. The word ‘fire’ appears ten times, as do the words ‘smoke’, ‘wind’, ‘flames’ and ‘volcano’. It narrates the speaker’s intense engagement with a broken mother–father relationship. Please share your process of writing this poem.

TM: I was recently asked this question of process about another piece of work where repetition is also very present. I do not have an answer for this. The music is something that emerges in the writing of the poem. In editing, I might intentionally pick a word or another. Swap a melody for another. But in the writing, the words emerge as if called by the last. This poem was inspired by Safia Elhillo’s ‘Vocabulary’. I was newly curious about a closed selection of words.

MX: I enjoyed the final poem, ‘peace offering’. The last three lines are calming and comforting in their simplicity:

you see

these are the days

of the sweet treaty

What was also most striking to me as I reread this collection was the arrangement of the poems. I do not recall reading a poetry collection and being alert to what reads like a smooth sequencing of work. I imagine it took a lot of intentionality—but maybe not?

TM: I draw a lot of inspiration from music. I studied, for example, the Sesotho book of hymns, and observed the sequencing of the songs. I also listen to albums in full and observe how each song cascades into the next. My process is similar to that of album-making. I’m interested in a chronology that is not time-bound or linear. An order that is disorderly and surprising.

MX: Wow, that’s so interesting! I know next to nothing about music. Thank you for this lesson. The cover of the chapbook is vibrant, intense and complex. I was curious about the artist, Ficre Ghebreyesus, and when I read his fascinating biography and saw the full version of the artwork I wondered further about the journey that ended in this choice. Please share the story.

TM: The African Poetry Book Fund, I believe, selects art for the collections that is resonant with the work. I didn’t choose any of the covers for my books, but if I had, I would have chosen the same images. Both are true mirrors of the work.

MX: From Ashley Makue in i know how to fix myself to Thabile Makue in 2020, when you released ‘mamaseko, published by University of Nebraska Press as part of the African Poetry Book Series. There are 73 poems from page 3 to 124. Publishers—South African publishers that I know—do not often assemble so many poems in one book. What was the process that led to the publication of ‘mamaseko?

TM: First, I want to address the name change. Through writing ‘mamaseko and migrating to the United States, I took back my birth name, Thabile. For many years I couldn’t answer to this name. It called me something I couldn’t access in myself. During the time when ‘mamaseko was being published, I was also in initiation for my spiritual work. Those processes returned my name to me.

After entering the Sillerman prize, I continued to seek publishers locally in South Africa, but I was unsuccessful. I was aware that the African Poetry Book Fund sometimes published collections that hadn’t won the prize. I had the courage to ask. And the response, I will never forget, was unanimously yes. I wanted a full body of work, so I submitted a lengthy manuscript.

MX: The cover image of ‘mamaseko has a calming feel to it—the couch, the embroidered fabric, the covered torso and the hard-to-see feet—and it is also inviting. It looks like a photograph, to my eyes, but I couldn’t see an acknowledgement of the photographer or artist. Is that a photograph?

TM: The cover was chosen by my publisher. I was in the process of migration when I first saw it and, though I loved it, my life was upside down at that point and I never learned more about the artist. I have been curious about it for a long time, but I feel too embarrassed to ask.

MX: In the ‘li tebogo’ section of the book you acknowledge the late Patricia Miswa for giving you your first writing job. I read her biography online.

TM: I am haunted, still, by Patricia’s death. Her vision for a Black and African fashion magazine was so important to me. We shared a great love of fashion and beauty, and the desire for both to express stories of Blackness. I know it is not my work, but I hope something emerges that answers her longing.

MX: Thank you for the glossary in ‘mamaseko. The words I knew were: ‘bolokoe’, ‘mantsoe’, and ‘mosebetsi’, which sound very much like isiZulu ones: ‘ubulongwe’, ‘amazwi’ and ‘umsebenzi’. I learned about ‘mali’ and ‘mollo’ long ago, I don’t even recall how. The rest of the section titles, ‘mele’, ‘mele oa bobeli’, ‘naha’, ‘secheso’, ‘popelo’, ‘pheko’ and ‘phupjane’, are all new to me.

TM: I love Sesotho. I am terribly sad that I am losing the language—forgetting some words … I wanted the vocabulary I built for ‘mamaseko to include these words. A lot of the English words were translated.

MX: Your poetry-infused essay—or is it poetry interspaced with prose?—published in the 2019 New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent (edited by Margaret Busby) is such a rich tapestry of family lineages that it is just perfect for the book. I imagine you wrote it specifically for this anthology. Maybe not? What led you to write ‘the ancestry of sadness’?

TM: At the time, I was very interested in essays. And I wanted to experiment with lyric essays. I was honoured to be invited to submit for the anthology and I wanted to write something special.

MX: You acknowledge Thandokuhle Mngqibisa and Vuyelwa Maluleke for editing this collection. What specific takeaways do you have from being edited ‘masterfully’ by these two poets?

TM: Both Thandokuhle Mngqibisa and Vuyelwa Maluleke are incredibly talented writers—and even better editors. They offered clear, actionable critique. From Thandokuhle, I learned to write boldly—to say what I meant to say. And from Vuyelwa, I learned to write precisely—to say it in exactly the way it needed to be said.

MX: You were the communications director for the heartbreaking research published in Through their Eyes: Stories of Reflection, Resistance, and Resilience on Juvenile Incarceration from San Francisco Cis and Trans Young Women & Girls, Trans Young Men & Boys and Gender Expansive Youth. Reading this report really broke my heart. Please write a poem that reflects on this research project.

TM: See above

MX: The poem ‘giving birth to my father’ opens with this stanza:

you taste your father’s

ejaculation from your mother’s mouth

your children are born

feet first

with faces that twist and twitch

and mouths full

of so much poison

your nipples turn black

and everything you sow

grows smoke

talks fire back to you

And the six last lines:

your mother let a rotten man

pee in her

now your body is sick

and all your children are maggots

who grow wings soon enough

and leave you

Here is poetry speaking so eloquently and with supreme erudition. While it reminds me of your poem ‘mantsoe’, it also leads me to the question: what is your journey with words, languages and the writing of poetry?

TM: I don’t recall when I learned my second language, English, but for as long as I can remember I’ve been engaged in translation. I grew up surrounded by people who spoke other languages, and I learned those too. As a communicator by profession, I’ve always seen language as having this fundamental function. There are things I haven’t known simply because I didn’t understand the words used to describe them.

That’s why I’m intentional about the words I choose and why I keep my vocabulary understandable. I want my reader always to be able to enter the poem because they can understand the words. I’ve long wished for my mother and grandmother to understand my work, but they could not. After my recent reading at the Calabash Literary Festival, women my mother and grandmother’s age came up to me to say that my work resonated with them. That made my heart full. The language I choose is for them; that’s whose poetry I write.

As for the writing process itself, inspiration often comes as a spark. I start writing, and then the words follow each other like a kind of spell. It’s in the editing that I really begin to have command over them.

MX: The poem ‘and these are eyes’, which begins the second section, ‘mele’, and the poem ‘not to forget’, in the section titled ‘pheko’, are formatted in two columns, which makes reading so much fun. How did you arrive at this decision for these specific poems? Put differently, is there something inherently similar in the content of these two poems that invited or demanded this formatting?

TM: There is a duality in both poems that I wanted to express in the form. I will admit that I am married to free verse. This preference is similar to my penchant for lowercase and no punctuation. I am intrigued by the possibility. Letters cascading up and down, free to become or not. I like to read poems in that form. Though I do understand that it is fun to read in different forms.

MX: The ‘mele oa bobeli’ section has poems titled ‘root body’, ‘year body’, ‘blood body’, ‘time body’, ‘too many body’, ‘fight body’ and ‘wound body’. These were extremely challenging for me to read, so I read them numerous times. ‘blood body’ ends with the potency of these lines:

and i am afraid

of the other side

beyond the

prayer walls

where the war has come

where the death has come

where the body has awoken

I cannot wait to read a scholarly article on your poetry because I am curious about how others read your work.

TM: This collection of poems was seeded by a poetry event I co-created with Vuyelwa Maluleke, called ‘this body is’. We were curious about the body, and wrote many poems to understand it. These poems emerged as answers. A body is the root. A body is a question, a hunger. A body answers …

MX: From the section ‘naha’, the short poem ‘refugee bones’ resonates so much with the endemic violence against women and girls in South Africa. One could change it ever so slightly by replacing the individual speaker to the plural. From

battle breaks out over my mother’s body

a blood bath spilling over

marking everything

she seeks asylum in a man

sets up camp over his chest

with a daughter on her back

i do not have a home

my country is a rotting man

To this version:

battles break out over our mothers’ bodies

a blood bath spilling over

marking everything

they seek asylum in men

set up camps over their chests

with daughters on their backs

we do not have a home

our country is rotting men

How do you deal with the emotion when writing poems about pain?

TM: I love this edit. Gorgeous. When I was younger, I would find those writing spells quite demanding and exhausting. But now I enter them to grieve and commune with whatever darkness I find there. I have learned that this opaque place is a treasure house. I come back with treats every time.

MX: One of the things I love about poetry is that it is possible to enjoy reading some poems even if I don’t fully understand them. Maybe this comes from my innate love for mantsoe. For instance, the poem ‘out of battle’ has lines that I get and metaphors I find interesting—for example ‘waiting is waking’ and ‘love makes you a city’—but I have failed to understand it wholesomely. Yet I remain content, sitting comfortably inside questions.

a word summons us from sand

places boats where rivers were borders

oceans turn into trains

hours are trees

waiting is waking

continents are country

in summertime

love makes you a city

dressed in pick clouds

this is geography

your body is honey

poured over all the lines

Have you had a similar experience with poems by others?

TM: Yes, absolutely. I have an appreciation for some mystery. Entering a poet’s secret.

MX: Your subtle humour springs up unexpectedly in some poems, like ‘marriage distress signal’. This poem and its curious metaphors made me laugh:

marry an ocean

arrive on a mud boat

heavy

sinking

labor a girl

for balance

paddle into the tide

capsize

and then set the girl

on fire

for help

TM: I often find that this is lost on others. I have a dark humour. I think the world is so terrifying and brutal, we ought to laugh about it.

MX: I searched for scholarly engagements with your poetry without much success. Please direct me to what you are aware of, in case I missed it.

TM: I am not yet aware of any.

MX: What is your approach to the various genres in which you write? How does poetry navigate its essence in your writing in other genres?

TM: Much of my other writing relies primarily on skill, especially in my communications work, where I write to influence. Poetry, though, is truly special to me. It’s skilful, yes, but also pretty and playful. Some poems are meant only for beauty. Occasionally, I carry that inclination towards the aesthetic into my other writing, and create marketing copy that is slightly beautiful.

MX: Are you connected to the poetry circles where you live currently? How does it work compared to the South African poetry scenes you may have been a part of?

TM: My joy is a monthly poetry reading event called ‘Readings at Sunset’. It is a queer and trans space, and every other month only Black writers read. It’s in the afternoon at a plant shop in Leimert Park, a historic Black neighborhood in Los Angeles. Most of the writers are not professional poets, which is greatly refreshing. I go dancing once a month with this same community at a rooftop bar in Hollywood for a house party called ‘Casual’. I love this community very much.

MX: The back cover blurb of ‘mamaseko reads:

Named after the poet’s mother, ‘mamaseko is a collection of introspective lyrics and other poems dealing with the intersections of blood relationships and related identities. Thabile Makue questions what it means to be beings of blood—to relate by blood, to live by blood. In her poems, Makue looks for traces of shared trauma and pain and asserts that wounds of the blood are healed by the same.

I enjoyed just how relatable your poetry felt because of the holding essence of ‘blood’. Thank you for agreeing to this engagement.

TM: Thank you so much for a thoughtful and interesting conversation. I had a lot of fun answering your questions.

- Makhosazana Xaba is a Patron. Xaba is an author, translator, and poet. She has written four poetry collections, these hands, Tongues of their Mothers, The Alkalinity of Bottled Water and The Art of Waiting for Tales. Her debut short story collection, Running and other stories, was a joint winner of the 2014 South African Literary Awards and Nadine Gordimer Short Story Award. Xaba has edited several books, including Our Word, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2015, Queer Africa: Selected Stories (with Karen Martin) and Noni Jabavu: A Stranger at Home (with Athambile Masola). Her latest book is Izimpabanga Zomhlaba, an isiZulu translation of The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon.