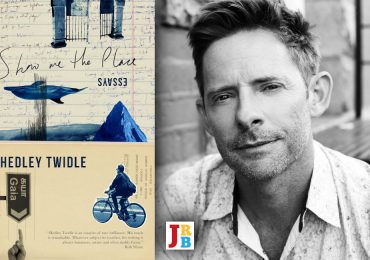

Ursula K Le Guin’s masterpiece was published fifty years ago this year. In a literary outtake from his most recent book, Show Me the Place, Hedley Twidle pays tribute to a wondrous imagination.

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, compiled by Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi, comes in at 2000 entries and 700 pages—a tribute to the deep human urge to make up other worlds (and draw maps of them).

Paging through, you might recognise names from childhood: Middle-Earth, Earthsea and Narnia are there. So are Kôr, Lilliput and the Island of the Roc. Jurassic Park and Hogwarts were added in the second edition.

Then there are worlds encountered later in life: Gabriel García Marquez’s jungle village Macondo from One Hundred Years of Solitude, with its plagues of amnesia and butterflies. The Pacific island of Gondal, dreamed up by the Brontë sisters. Many islands of course: an island is the most available model, the starter pack, for dreaming up a distant, self-contained elsewhere. Utopia and Erewhon are there; so are Atlantis and Azania, Lotus-Eaters Island and Caliban’s Island (see Prospero’s Island).

‘We agreed that our approach would have to be carefully balanced between the practical and the fantastic’, Manguel writes in the foreword:

We would take for granted that fiction was fact, and treat the chosen texts as seriously as one treats the reports of an explorer or chronicler, using only the information provided in the original source, with no ‘inventions’ on our part.

The straight-faced approach suits the genre of utopia. The defining characteristic of a literary utopia (writes Gregory Claeys) is ‘its nonexistence combined with a topos—a location in time and space—to give it verisimilitude’ (that is, the semblance of being real). This sets it apart from more free-floating visions of paradise, nirvana and the Golden Age. The better places of myth and religion tend to occupy another plane of existence; utopias have a more worldly address.

So where on earth to locate a utopia? Where to place the non-place? You can opt for the close at hand—a secret valley, as in the Chinese fable of the Peach Blossom Spring—or the other side of the world. With the circumnavigation of the globe, the antipodes become a favoured location. Thomas More’s Utopia and Samuel Butler’s Erewhon impersonate travelogues to places as far away as possible from their first readers—the New World for More, New Zealand for Butler—and here the utopian imagination becomes entangled with colonialism and empire. Brave new worlds for some mean dispossession and enslavement for others.

As more and more of the earth’s surface is mapped by cartographers, speculative worlds migrate to Arctic wastes (Mary Shelley), the planet’s hollow core (Jules Verne), the deep ocean (Verne again) or an exoticised African interior (H Rider Haggard). Some are relocated into the past or future with time machines, or shifted into alternative streams of history: all strategies used in nineteenth-century bestsellers by Edward Bellamy, William Morris and HG Wells. Or (another refuge for the speculative imagination) what about a counter-history where Africa, Asia and the Americas were never colonised?

With space travel in the twentieth century, the astronomical solution comes to dominate: moving off-world and inventing new planets altogether. And so the ancient literary tradition of utopia merges into science fiction; but these more otherworldly locales are not included in the Dictionary of Imaginary Places, since (as the editors explain), the list threatened to become endless:

Given the vast scope of the imaginary universe, we had, for practical purposes, to establish certain limits. We began by deliberately restricting ourselves to places that a traveller could expect to visit, leaving out heavens and hells and places of the future, and including only those on our own planet.

Places that a traveller could expect to visit? For Narnia you go through a wardrobe, but how to get to Middle-Earth or Earthsea? Then again, you know what they mean: both realms are somehow earthy, earthly (and contain the word after all).

Le Guin’s archipelago—a world of islands with wonderful names: Gont, Roke, Lorbanery, Jessage and The Hands—is well represented in the Dictionary. But because of the rules set out by Manguel (strictly non-extraterrestrial), her other, science fictional universe, the world of the Ekumen, does not appear. As Margaret Atwood remarks, the remarkable thing about this writer is that she conjured not one but two world-altering imaginative realms—one of fantasy and one science fictional—and did this in parallel.

The science fiction begins as follows, from the prologue to Rocannon’s World (which appeared in 1966 with a gloriously bad cover):

How can you tell the legend from the fact on these worlds that lie so many years away?—planets without names, called by their people simply The World, planets without history, where the past is the matter of myth, and a returning explorer finds his own doings of a few years back have become the gestures of a god. Unreason darkens that gap of time bridged by our lightspeed ships, and in the darkness uncertainty and disproportion grow like weeds.

In trying to tell the story of a man, an ordinary League scientist, who went to such a nameless half-known world not many years ago, one feels like an archaeologist amid millennial ruins …

Over many novels and short stories to follow, Le Guin elaborates this concept. There is an organisation—the League of All Worlds, later the Ekumen—that sends its scientists and observers to different planets, seeking to understand the various paths that civilisations and social organisation have taken. The word Ekumen evokes the ancient Greek oikoumene, meaning ‘the inhabited world’ (the word stem is from oikos—household, family, hearth—which also gives us words like economy and ecology).

Like a benign United Nations of space, the Ekumen is on a diplomatic mission to bring different humanoid societies into the League, linked by a simultaneous communication device called an ansible. The peoples on all these various worlds (we gradually learn) all descend from a civilisation called Hain. The Hainish were ancient interstellar colonists who ‘seeded’ various planets with human populations, setting up the premise for Le Guin’s grand series of thought experiments. What is the nature of human nature, given different environmental parameters, different social arrangements, and even different trajectories of genetic modification and organic evolution?

In her 1968 masterpiece The Left Hand of Darkness, she imagines the icy world of Gethen (Winter), where inhabitants are mostly androgynous and ambisexual—there is no gender in the human sense. Once a month, in a kind of biological oestrus or sexual heat called kemmer, Gethenians briefly become either ‘male’ or ‘female’ and go to orgiastic, perfectly normal kemmer houses—but there is no way of knowing which way they will swing, so they occupy both roles many times in the course of a life. Trying to navigate all this is Genly Ai, an envoy from the Ekumen—or a Mobile as they are called: diplomat-observer-scientists who operate under very strict guidelines about how to interact with host planets, but are often drawn into political intrigues and danger.

In 1974’s The Dispossessed (subtitled ‘An Ambiguous Utopia’), Le Guin imagines into being the new world of Anarres—anarchist, feminist, egalitarian but arid and ecologically poor—that is locked into the orbit of the old world Urras: profit-driven, hierarchical, unequal, but lush and beautiful.

160 years before the novel opens, Anarres has been settled by idealistic revolutionaries and exiles from Urras. Now one of the Anarresti, a brilliant physicist named Shevek wants to visit Urras in order to further his scientific research into the Principle of Simultaneity, and to re-establish contact between the two worlds. Shevek’s work will result in the ansible, the communication device that provides a technological underpinning for the Ekumen. And so even though The Dispossessed is the fifth Hainish novel that Le Guin published, it gives us the backstory to the cycle: in terms of internal, imaginative chronology, we are right near the beginning of her universe.

Anarres and Urras are located in the solar system of Tau Ceti, a real star at a distance of just under twelve light years from Earth (or Terra, as it is referred to in the novel). Like all good utopias, The Dispossessed operates (in some sense) within the parameters of scientific possibility. And it has coordinates—a topos—within our known universe. But if Anarres is theoretically possible and possibly habitable, it is only just so. ‘Nowhere in the geography of utopia’, wrote one reviewer, ‘is there an island apparently so fundamentally hostile to human flourishing’.

When Shevek leaves Anarres for Urras, he is reversing the usual trajectory of utopian literature. He is travelling not to the New World, but from it. Not towards utopia, but away, back to the Old World, the dystopia that his people once walked away from.

Or, at least, this is what he has been brought up to think. Anarresti schoolchildren are taught that Urras is a nightmarish place of injustice and inequality, that its inhabitants are heartless ‘propertarians’. They learn about a mythic, almost unimaginable figure: the ‘Beggarman’. Vice versa, many on Urras see the Anarresti as hairy, unkempt puritans: ‘starveling idealists’ whose social experiment is really an economic colony that can only exist because of mining exports that travel on space freighters from Anarres to Urras.

The double planet system is used to show how each society needs an Other to define and construct itself against—‘Our earth is their Moon’, says one character, looking from Anarres to Urras, ‘Our Moon is their earth’—and it is not always easy to see where the truth lies. Shevek’s voyage sets in motion a range of thought experiments that reach into all aspects of human life—family, sex, work, class, leisure, gender, education, food, shopping—as the norms of each world in this diptych keep estranging those of the other.

He has grown up in a world where wood is never burned for warmth, where people eat two meals a day and books are printed (because paper is so scarce) with tiny characters and narrow margins. Organic evolution has produced no insects on Anarres, no quadrupeds, nothing more complex than fish and non-flowering plants. It is a lonely planet.

Imaginary worlds change as they move through time and space. When The Dispossessed appeared in 1974, most readers responded to the questions of political economy that the novel activates—all too human histories. But today, it’s the ecological loneliness of Anarres that seems most haunting to me. A world without birdsong. A place where spring is silent and fruit trees must be pollinated by hand (now happening in parts of Terra, as insect populations collapse.)

I read the novel for the first time during the Covid pandemic, and have returned to it many times since. It brought solace and became a guiding, almost talismanic work in thinking about other worlds of possibility, whether real or imagined. If George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is the twentieth-century dystopia that continues to exert the strongest gravitational force in world literature, then Le Guin’s novel could be seen as its lesser-known utopian counterpart: two powerful speculative fictions orbiting each other in imaginative space.

Le Guin’s Hainish cycle—with its enlightened League of All Worlds and its Nearly as Fast as Light ships—in some ways prefigures the warp speed Federation of Star Trek. But her universe is less obviously Western or American. The NAFAL ships tend to have names like Mindful rather than Enterprise; and Le Guin’s protagonists, if you read closely, tend not to be Caucasian: they are brown, copper-coloured or (like Genly) dark-skinned. Her universe is shaped by a more global set of influences, especially Taoism and Buddhism, as well as the Native American societies written about by her father (an anthropologist) and mother (historian).

The extra-terrestrial thought experiments, in other words, are intimately related to earthly stories of dispossession and colonisation; but also (the more utopian dimension) to the cultural shockwave released by the European voyages of discovery and extended in time by the nineteenth-century disciplines of archaeology and anthropology: that things have not always been as they are (and could be otherwise again). ‘I’m interested in anthropology because I’m interested in human possibilities’, the anarchist thinker David Graeber once remarked, ‘and in a way, there’s always been an affinity between anthropology and anarchism, simply because anthropologists know that a society without a state is possible. There’s been plenty of them.’

This is the challenge that Le Guin sets herself in The Dispossessed: to write an anarchist utopia. To imagine a better world but one without state control or centralised authority (though much of the plot turns on whether this kind of control is subtly reinstating itself on Anarres). Le Guin is a profoundly anti-authoritarian writer, allergic to dogma, doctrine or any kind of party line. Reflecting on what led her to write the book, she remembers her involvement in protests against the Vietnam War, and then what came after:

But, knowing only that I didn’t want to study war no more, I studied peace. I started by reading a whole mess of utopias and learning something about pacifism and Gandhi and nonviolent resistance. This led me to the nonviolent anarchist writers such as Peter Kropotkin and Paul Goodman. With them I felt a great, immediate affinity. They made sense to me in the way Lao Tzu did. They enabled me to think about war, peace, politics, how we govern one another and ourselves, the value of failure, and the strength of what is weak.

So, when I realised that nobody had yet written an anarchist utopia, I finally began to see what my book might be.

‘A whole mess of utopias’: a nicely counter-intuitive phrase. Not the rationalist blueprint of perfection (with totalitarian undertones) that has tainted the genre from Plato’s Republic to More’s island and Marx’s classless society. But rather an overlapping, plural, anarchic series of utopian imaginings: an untidy collection of thought experiments in what makes life worth living, and one that does not disavow the messiness of human relationships and psychology. Le Guin’s ambiguous utopianism admits the awkwardness, emotional clutter and novelistic detail of what happens when idealism takes shape in the story of actual lives, amid the multi-variables of finely drawn social worlds.

The hard-headed believability of places like Anarres, Urras and Gethen is the marvel of these books, though part of it emerges from Le Guin’s understated and controlled language. An ambisexual kemmer house is barely worth going into in The Left Hand of Darkness, which often reads more like a tightly plotted political thriller (Le Guin as Le Carré) and employs the ancient narrative method of relating the most outlandish things as if they were entirely normal (which, for the inhabitants of Gethen, they are). In these novels, the SF apparatus is generally unobtrusive and technology is not fetishized—throughout her career Le Guin was dismissive of the kind of masculinist science fiction where ‘gleaming spaceships’ hurtle out across the galaxy, ‘ships capable of blasting other, inimical ships into smithereens with their apocalyptic, holocaustic ray guns’ (Language of the Night).

Though it took a while to find her more restrained and confident, cerebral voice. As the overblown prologue of Rocannon’s World suggests, in the early work the fantasy and science fictional strands are still tangled together. The result can be a little silly, or (like Star Wars) a bit kitsch: a pastiche of space age and bronze age, futuristic visions and furry creatures, dwarves and starlords. There was ‘a lot of promiscuous mixing going on’, Le Guin admitted in The Language of the Night, putting it down to ‘beginner’s rashness’ and ‘the glorious freedom of ignorance’. But ‘red is red and blue is blue’, she came to realise, ‘and if you want either red or blue, don’t mix them’.

As the SF cycle develops in parallel with the Earthsea books, Le Guin slowly disentangles the two impulses: ‘Along in 1967–8 I finally got my pure fantasy vein separated off from my science fiction vein, by writing A Wizard of Earthsea and then Left Hand of Darkness, and the separation marked a very large advance in both skill and content’. Ambisexual, ambidextrous: from here on she writes both right and left-handedly. The fantasy books become more self-contained and truer to their inner laws; the SF works become more austere, psychological, plausible (no more elves or invisibility cloaks), reaching maximum ambition and conceptual scope in the ambiguous utopia of The Dispossessed: the most unlikely, most convincing better place in world literature (the only one I’ve ever been tempted to leave Earth for anyway).

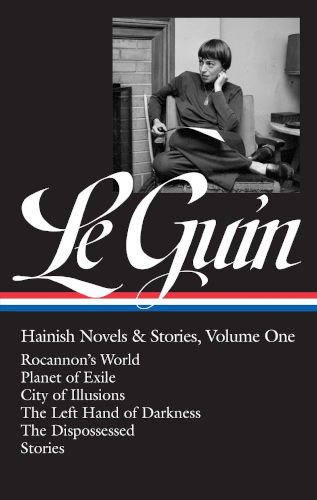

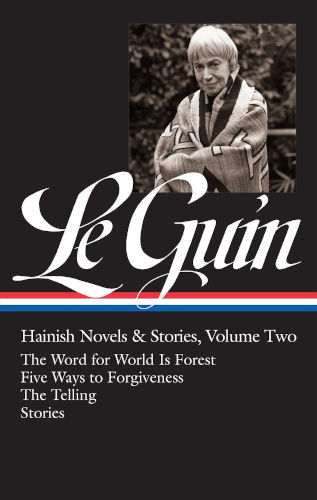

You can track Le Guin’s gradual absorption from genre fiction into the literary canon via her book covers. From the nineteen-seventies the jackets become less lurid and pulpy, more abstract and thoughtful—until eventually all the Hainish Novels and Stories are collected in a two-volume box set from the Library of Congress, with a picture of her on each book. On volume one she is youngish and elfin, wearing loafers curled up under her on the chair, an androgynous SF blouse/trousers combo and holding (always likely to surprise you) a pipe. On volume two she is the elderly, legendary Le Guin, swathed in a medicine blanket: the Arch-Mage of Portlandia, who (a few years before she died) became a meme for remarks she made in a 2014 National Book awards speech:

We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable—but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.

The haircut is the same in both pictures, though: a sleek bob that landed fully formed on her head like a UFO, and which in its own way always seemed to be making a career-long statement about SF and gender.

In her introduction, Le Guin is not so sure about the ‘Hainish’ label. It implies a coherent fictional universe with a well-planned history, a methodical cosmos creation with plans and timelines early on in the process:

I failed to do this. Any timeline for the books of the Hainish descent would resemble the web of a spider on LSD. Some stories connect, others contradict. Irresponsible as a tourist, I wandered around in my universe forgetting what I’d said about it last time, and then trying to conceal discrepancies with implausibilities, or with silence. If, as some think, God is no longer speaking, maybe it’s because he looked at what he’d made and found himself unable to believe it.

On the other hand, she sometimes scolded writers too lax with what she saw as the strict demands and codes of the science fiction canon. In the 1977 essay ‘Do-It-Yourself Cosmology’, she inclines in the other, more stringent direction with regard to world-building and universe-creation:

As soon as you, the writer, have said ‘The green sun had already set, but the red one was hanging like a bloated salami above the mountains,’ you had better have a pretty fair idea in your head concerning the type and size of green suns and red suns—especially green ones, which are not the commonest sort—and the arguments concerning the existence of planets in a binary system, and the probable effects of a double primary on orbits, tides, seasons, and biological rhythms …

If you’re bored by the labour of figuring all this out, she continues, then you shouldn’t be writing science fiction: ‘A great part of the pleasure of the genre, for both writer and reader, lies in the solidity and precision, the logical elegance, of fantasy stimulated by and extrapolated from scientific fact’.

Given that none of Le Guin’s science fictional worlds made it into the The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, I tried writing an entry for Anarres elsewhere, creating a page for this anarchist planet on Wikipedia, one of the great utopian projects of our time and place.

~~~

- Hedley Twidle is a writer, teacher and researcher based at the University of Cape Town. His book Firepool, a collection of essays, was published by Kwela in 2017. Experiments with Truth, an academic study of life writing and the South African transition, came out in 2019. A new collection of essays and non-fiction, Show Me the Place, was published by Jonathan Ball in April 2024. His work has appeared in a range of local and international publications, including the New Statesman, Financial Times and Harper’s magazine.