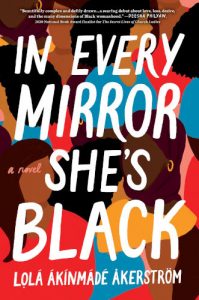

Shayera Dark reviews In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lọlá Ákínmádé Åkerström.

In Every Mirror She’s Black

Lọlá Ákínmádé Åkerström

Head of Zeus, 2021

In Lọlá Ákínmádé Åkerström’s debut novel In Every Mirror She’s Black, the weight of Blackness threads together the lives of three women who wind up in Stockholm under the influence of Jonny von Lundin, scion of a highborn family with close ties to Sweden’s monarchy.

The story opens with Kemi, an ambitious Nigerian-American marketing executive incapable of replicating her successes at work in her love life. Her romantic ‘dossier of shame’ has imploded her self-esteem. So when von Lundin’s company recruits her as their diversity and inclusion director, following a disastrous campaign that exposed the firm’s racial blindspot, she packs up her life in America with the intention of remaking it in Sweden.

Similarly, a brief encounter on a routine flight finds Brittany, an American with Jamaican roots, entering an intense, asphyxiating romance with the quirky Swede, whose deep pockets and far-reaching connections radically transform the bored flight attendant’s station in life.

Finally, having lost her family to war in Somalia and the raging seas, Muna hopes to start a new life in Stockholm as a janitor after leaving Solsidan, the picturesque, von Lundin-funded refuge for asylum seekers in the Swedish countryside.

Before long, various forms of discrimination, subtle and otherwise, greet each woman as they attempt to navigate a society adamant on conformity and heterogeneity, and cool to the idea of assimilating migrants.

An immigration officer stresses to Muna that her ‘“strong” culture’ will prevent her from becoming ‘fully Swedish’, an indirect reference to her complexion and jilbab, as well as Sweden’s dislike for ‘sharp edges that stuck out’. As the sole Black person at her workplace, Kemi too sticks out. She wonders if she’s a token, hired to burnish the company’s image, a suspicion that deepens after Jonny hands over the business account she won thanks to her inclusive ad campaign to his best friend. What’s more, her colleagues take to questioning her ability and role behind her back, despite her glowing credentials.

Meanwhile, Brittany discovers her presence rattles the von Lundin clan, despite her acceptance of and dexterity with Jonny’s medical condition. To them, her skin tone represents a breach of carefully preserved traditions, a jarring intrusion into their rarefied circle and world of secrets—a sentiment they express through passive-aggressive acts and belittling remarks. For his part, Jonny defends Brittany, even as she begins to suspect that his ardent support emanates from a darker, less altruistic place.

Far away from Brittany’s glitzy milieu, Muna contends with life in the grim, barren suburbs, a world designed to keep immigrants in their place, away from centres of productivity and mainstream society. This alienation inflames young immigrant residents, weary of a life of limited prospects dictated by their skin tone. ‘They won’t look at us,’ cries an immigrant boy, summarising Sweden’s contemptuous attitude towards them. ‘Who doesn’t look at another human being. Who doesn’t?’ When a security guard manhandles a Somali boy for stealing a chocolate, their frustration bubbles over and a riot ensues, one that leads to jail terms and possible deportation for victims of a societal malaise. Muna, too, feels the effects:

‘For days after the riots, as she roamed around downtown Stockholm, strange eyes lingered on her for an extra second or two, washing over her hijab with suspicion.’

That the Swedish press focuses inordinately on khat, a recreational drug associated with Somali men, as opposed to the cocaine consumed by the country’s elite isn’t lost on Muna. She recalls the prejudicial ‘war on drugs’, the global campaign led by the United States, which saw sympathy abound for white peddlers and users of opioids, but not for other racial groups and their drugs of choice.

In uncomplicated but engaging prose, Åkerström’s Afro-Swedish characters highlight the distinctions in race relations between the United States and Sweden. While the former accepts or assimilates multiple backgrounds, to a degree, the latter expects national identity to take precedence. America’s public distaste for blackface and tolerance for Black women in positions of power denotes another major difference: when Kemi mentions to a Nigerian doctor turned nursing aide that she relocated from America to Sweden for work, he quips that she’s made a mistake. ‘And in all that time you have been here, have you seen anybody like Oprah?’ he asks. ‘At least in America, you’re fighting your enemy in broad daylight.’

Even for immigrants fluent in Swedish, a supposed marker of cultural acceptance and assimilation, racism persists, as witnessed when Brittany freely enters the same shop a Swedish-speaking Black woman is barred from accessing. In that moment, Brittany vows to cloak herself with her American-accented English rather than suffer fresh indignities wrought by speaking the language of her new home.

Åkerström artfully tackles classism and its manifestation across cultures. In egalitarian Stockholm, deducing one’s socioeconomic standing and inherent value involves asking what area of the city one resides in. As a newly minted von Lundin, Brittany expresses disdain for the lowly Muna, while Kemi wrestles with the idea of dating a security guard and how to explain the anomaly to her high-achieving Nigerian family.

Like most novels documenting the immigrant experience, instances of culture clashes abound In Every Mirror She’s Black, some harmless, others baleful. Reserved Swedish men that stare but won’t approach her confound Kemi, whose colourful wardrobe becomes the source of gossip among her monotoned colleagues. And in a bid to make Muna presentable at work, her Turkish boss advises she swap her jilbab for a hijab. ‘We’re in Sweden, for God’s sake,’ he asserts. ‘The freest place on earth!’

In the end, trudging through boulevards of love, deception, loss and dashed dreams, with little hope of redemption, all three women realise that neither material comfort nor right of abode offer reprieve from the myriad invisible cuts inflicted by a society irrationally hostile to the colour of their skin. For Åkerström’s characters, not a single mirror in Sweden provides a refuge.

- Shayera Dark is a writer whose work has appeared in publications that include LitHub, Harper’s Magazine, Al Jazeera, AFREADA, The Kalahari Review and CNN.