The 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah.

Gurnah becomes the first Black African writer to be awarded the prize since Wole Soyinka in 1986, and is the first Tanzanian writer to win.

Gurnah was awarded the Nobel ‘for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents’.

The prestigious award comes with a gold medal and 10 million Swedish kronor (about R17 million).

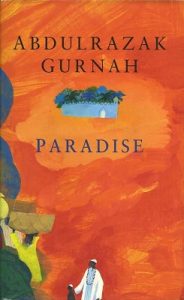

Gurnah was born in 1948 and grew up in Zanzibar, arriving in England as a refugee in the end of the nineteen-sixties. He recently retired as professor at the University of Kent. He has published ten novels and a number of short stories, and perhaps is best known for his 1994 historical novel Paradise, set in colonial East Africa during World War I, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Whitbread Prize for Fiction.

The Nobel Prize citation reads:

In all his work, Gurnah has striven to avoid the ubiquitous nostalgia for a more pristine precolonial Africa. His own background is a culturally diversified island in the Indian Ocean, with a history of slave trade and various forms of oppression under a number of colonial powers—Portuguese, Indian, Arab, German and British—and with trade connections with the entire world. Zanzibar was a cosmopolitan society before globalisation.

Gurnah’s writing is from his time in exile but pertains to his relationship with the place he had left, which means that memory is of vital importance for the genesis of his work. […]

Gurnah’s dedication to truth and his aversion to simplification are striking. This can make him bleak and uncompromising, at the same time as he follows the fates of individuals with great compassion and unbending commitment. His novels recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world. In Gurnah’s literary universe, everything is shifting—memories, names, identities. This is probably because his project cannot reach completion in any definitive sense. An unending exploration driven by intellectual passion is present in all his books, and equally prominent now, in Afterlives, as when he began writing as a twenty-one-year-old refugee.

Usually winners receive the Nobel from King Carl XVI Gustaf at a formal ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December, the anniversary of the 1896 death of scientist Alfred Nobel who created the prizes in his last will and testament, but the event has been cancelled for the second year in a row owing to the coronavirus pandemic. Gurnah was in fact watching the event online when he received a phone call from Adam Smith of Nobel Prize Outreach.

In the telephone conversation with Smith, Gurnah expressed his surprise at winning the award.

‘I thought it was a prank, I really did,’ he said. ‘Because these things are floated for weeks beforehand, or even months beforehand, who are the runners. It was not something that was in my mind at all. I was just thinking, I wonder who will get it?’

During the call, which was constantly interrupted by Gurnah’s other phone ringing, Smith pointed out that scientists who win Nobel Prizes often describe their work as ‘play’, ‘the joy of exploring’, and asked Gurnah whether he feels the same.

‘Well I feel joy when I’ve finished,’ he said. ‘But yeah, a lot of it is obviously something that is compulsive, compelling, something that writers keep going for decades, you can’t be doing that if you hate it. But I suppose it is both the pleasure of making things, crafting, getting it right, but it’s also the pleasure of getting something across, or giving pleasure, or making a case or persuading, and all of those kinds of things.’

The prize citation speaks of how Gurnah’s work deals with the fate of refugees and the gulf between cultures and continents, and Smith asked him about he views these divisions.

‘I don’t see that these divisions are permanent or insurmountable,’ he said. ‘This phenomenon of particularly people from Africa coming to Europe is a relatively new one but of course the other, Europeans streaming out in to the world, is nothing new, centuries we’ve had of that.

‘The reason it’s so difficult for a lot of people in Europe, for European states, to come to terms with this is perhaps a kind of miserliness, as if there isn’t enough to go around, when many of these people who come, come out of need and also because quite frankly they have something to give. They don’t come empty handed. A lot of them are talented, energic people who have something to give. So that might be another way of thinking about it. You are not just taking people in as if they are poverty stricken nothings. You are both providing succour to people who are in need, but also people who can contribute something.’

The Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded 114 times since 1909. 102 of the awards have gone to men and just sixteen to women. Alfred Nobel’s instructions for the award, indeed for all his bequeathed prizes, was that it should go to a person who during the preceding year ‘shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind’, and specifically in the field of literature, gnomically, the person who ‘shall have produced the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency’. He added that ‘no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates’.

Despite this, the only African writers to have won the Nobel Prize in Literature are Naguib Mahfouz (1988), Wole Soyinka (1986), Nadine Gordimer (1991), JM Coetzee (2003) and, arguably, Albert Camus (1957), who was born in what was then French Algeria (now Algeria), and Doris Lessing (2007), who was born in what was then Persia (now Iran) but spent much of her life in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

In 2019, in the wake of some controversy, including a sexual abuse scandal and criticisism directed at the Swedish Academiy’s overly secretive processes, the Nobel Committee revealed its new, less ‘Eurocentric’ and ‘male-centred’, criteria.

In October 2019, however, the academy indicated that it was also perhaps undaunted by the criticism, when it announced the concurrent winners for 2018 and 2019: Polish author Olga Tokarczuk and Austrian novelist and playwright Peter Handke—the latter another controversial choice, as an apparent apologist for far-right Serbian nationalism, and a vocal supporter of Slobodan Milošević.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature was won by American poet Louise Glück.