Header image: Brother George, by The JRB Photo Editor Victor Dlamini

Legendary South African photographer George Hallett has died, according to reports by his family on social media.

Hallett lived in Cape Town, and had been ill for some time. He was seventy-eight.

Hallett was probably best known for his poignant photographs of District Six in Cape Town, his portraits of African artists in exile, and his series of photographs of Nelson Mandela taken during the 1994 elections.

His daughter, Maymoena Hallett, posted on Facebook:

My father died peacefully in his sleep today, after a long illness.

We will always remember him for his light, his laughter, his boisterous personality, his outrageous jokes and being the life and soul of many a party.

Nobody can doubt his artistry in capturing beauty and joy in everything he saw through his eyes and his lens, nor his contribution to photography, particularly South African photography.

Rest In Power Papa G

Hallett was born in District Six in 1942, and grew up in Grassy Park and then Hout Bay, where he lived with his grandparents.

When he was a child, Hallett’s school in Hout Bay was converted to a cinema on weekends. In one of the few interviews he ever gave, with John Edwin Mason, published in Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies in 2014, Hallett recalled how those early movie nights, and his learning how the projector worked, shaped his aesthetic:

Once I figured out how that worked and this powerful light being projected across this dark space onto the silver screen, I went to sit closer. I became the camera when I was sitting in that movie house. I didn’t become the characters; I was the observer. Eventually when I became a photographer those powers of observing held me in good stead because when you do documentary photography you don’t direct the photography. You’re supposed to stand back and observe—or go forward or sideways—but you’ve got to photograph the reality in front of you. The other thing about being the camera, I also became aware that when the lighting changed, the mood changed, the music changed. So it introduced me to the makings of film. How is a film put together? I think that had a huge influence on me.

In high school, Hallett was taught English literature by the novelist Richard Rive, who also had a great impact on his artistic and political outlook.

As a young man Hallett worked as a street photographer and did some freelance work for Drum magazine. After District Six was declared a whites-only suburb under the Group Areas Act in 1966, forcing over 60,000 people to leave their homes, the author James Matthews and writer and artist Peter E Clarke persuaded Hallett to photograph the area before it was demolished and destroyed. The resulting series of photographs was later donated to the District Six Museum.

His first solo exhibition, a series of photographs of writers, artists, actors, dancers and musicians, inspired by The Sweet Flypaper of Life, Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s ode to Harlem, was held at the Artists Gallery in Cape Town.

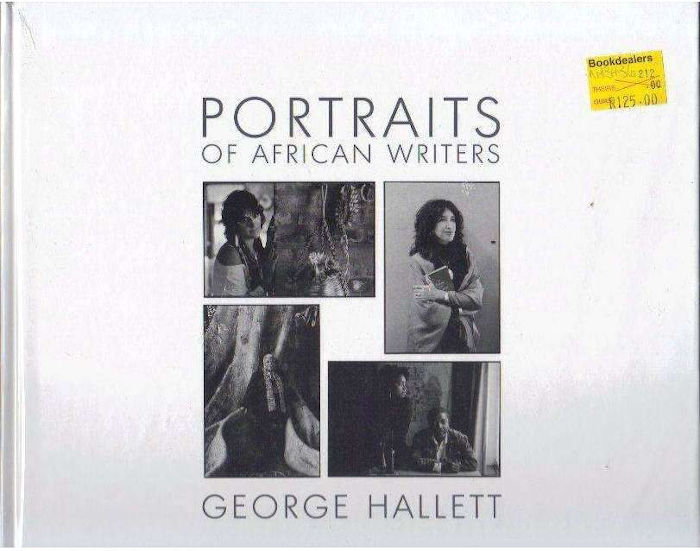

Hallett left apartheid South Africa in 1970 and went into self-imposed exile. He moved to London in the United Kingdom, where he made contact with other South African exiles such as Alex La Guma, Pallo Jordan, Dudu Pukwana and Dumile Feni, among many others. He also made contact with African writers such as Wole Soyinka and Ahmadou Kourouma in Berlin. A resulting book, Portraits of African Writers, made up of over 100 images, was published in 2006.

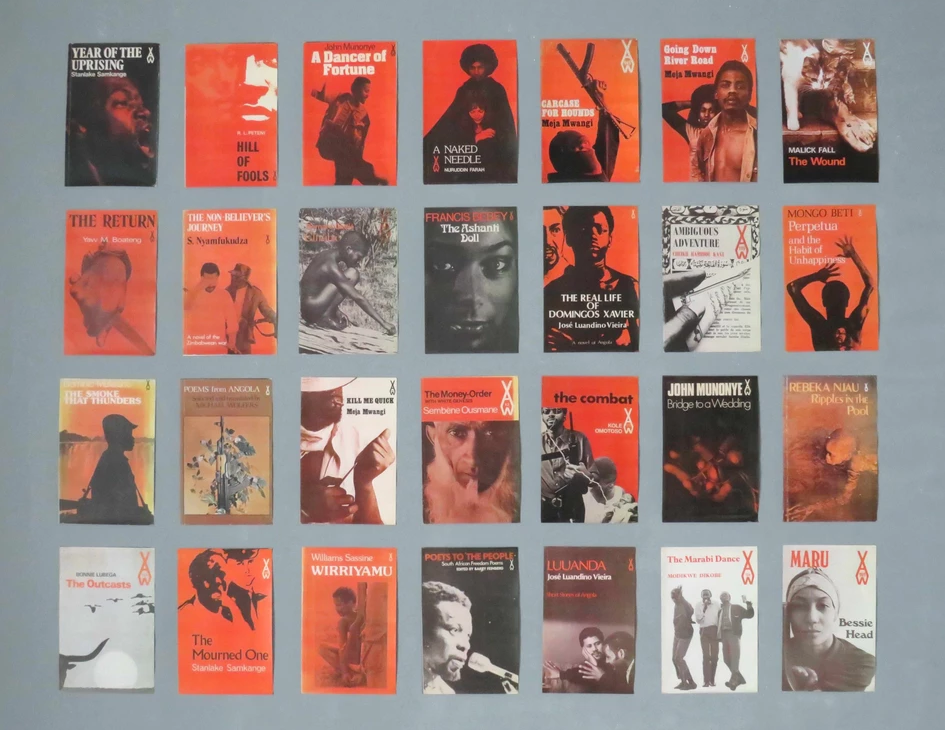

In London Hallett worked for the Times Higher Education Supplement and designed avant-garde book covers for the Heinemann African Writers Series.

His first European exhibition, with South African artists Gerard Sekoto and Louis Maurice, was held in Paris in 1971. Shortly after, he held a solo exhibition in the Westerkerk in Amsterdam, organised by the World Council of Churches.

In his interview with John Edwin Mason, Hallett said of this time:

I will never forget European society for allowing us South African artists to be creative. I began to experiment with photographic techniques. High-contrast film. Cutting out grey scales. Solarisation and creating a new visual presentation not practised before. I carried this over to creating record covers for the SA musicians in exile. […] What was denied to us in our homeland we were able to explore in London. We weren’t living on handouts. We were living on our creative powers and, we were very proud of it.

Hallett lived in Paris, Amsterdam and Zimbabwe, working in many areas including photography, teaching and farming, and the United States, where he taught at several universities including the University of Illinois. In 1980 he won the Hasselblad Award for Outstanding Contributions to Photography in Sweden.

In 1981, while teaching at a school in Washington DC, Hallett was asked why he chose not to ‘play white’:

I said, ‘Let me explain where I come from and what it means to be black. It’s not a question of pigmentation. It’s a question of how you feel about your society, how you feel about people around you, and how you feel about white people at large.’

Some of my brothers are darker than I am. My mother was very dark. So I said when you talk about coloured people in South Africa you can have one person in the family who is very dark and one who is almost white with blue eyes. It’s a mental attitude. (From his interview with John Edwin Mason.)

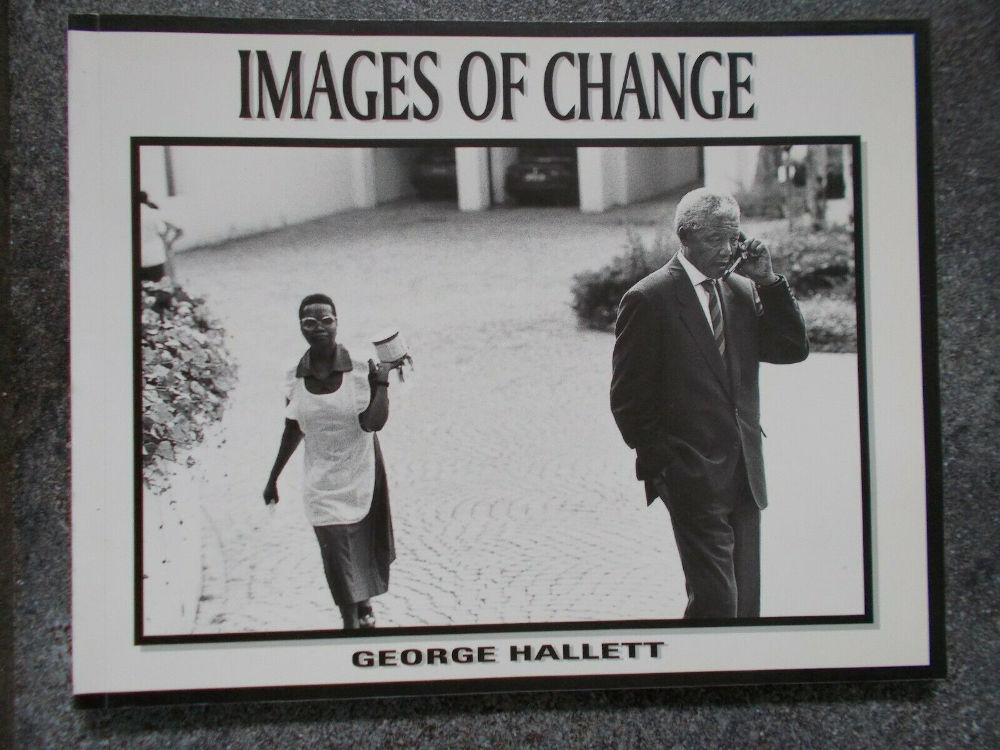

Hallett began working back in his home country in 1990, photographing Inkatha rallies and camps in KwaZulu-Natal, and spending a week with Archbishop Desmond Tutu at his official residence. In 1994 he was commissioned by the ANC and his friend Pallo Jordan to document South Africa’s first democratic elections, resulting in the book Images of Change. A series of photographs of Nelson Mandela taken during the elections won Hallett a Golden Eye Award from the World Press Photo in Amsterdam.

That picture with the women running towards Mandela was the first time they had actually seen him close up. And it was an incredible experience, because for the first time I saw the whole country, and the joy and the hope that people had. My God, I thought—it’s finally about to end; this crappy system of apartheid. And that was very inspirational.

—George Hallett, Then & Now, 2008

He finally settled back in Cape Town in 1995.

Hallett was the official photographer of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997, and produced many powerful works during this period, most notably the image entitled ‘Jann Turner with Eugene de Kock, TRC Headquarters 1997’.

Hallett exhibited across South Africa, Europe, and the US in a career that spanned over fifty years. His photographs are included in permanent collections all over the world, including the Schomburg Centre for research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library, the South African National Gallery, the Anne Frank Foundation, Amsterdam, and the Sonja Henie-Niels Onstad Collection, Oslo, Norway.

Hallett’s work is renowned for its humanity, its striking textures and sparse beauty. He delighted in being the silent observer, photographing people without them being aware of him. We will miss his presence nonetheless.