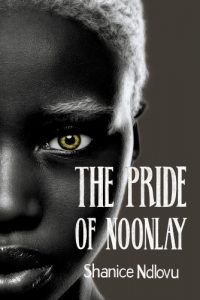

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Pride of Noonlay, the debut collection of short stories by Shanice Ndlovu.

The Pride of Noonlay

Shanice Ndlovu

Modjaji Books, 2020

Read the excerpt:

1.

The Walking Fish

There had been storms before, all of them threatening, and all of them worse than the last one. Yet something about the thunder that boomed through the walls settled in my marrow, as if marking the beginning of an imminent end. The candles flickered as a window shattered to shards, and lightning sent shadows scurrying over the ceiling.

In the Seasones we would all huddle in worship of such a storm. There the trees speak to us if we listen, and the earth warns us if we heed it. We are not pure sympathy folk like the stone throwers of She, or the wind talkers of Aiian, and yet, we have small sympathies of our own. We whisper to the arm that throws the spear, for how else will it know where to go? We pray to the ground so it will hold us.

I am a coarsened warrior of the warriors of Malajan in the dark of the Seasones, and I do not fear much.

Yet, I was terrified of this new land. Its earth owed me no allegiance, its trees did not speak, and its ground did not recognise the brown of my feet. When I was born, my mother did not know what to make of a daughter who would not cry. I was her first child, and she carried me to my father in a woollen shawl and leather basket. Fani stood at the edge of the ocean and watched the waves sweep between his toes, teasing and receding like a coy lover.

He lifted me from the basket and carried me into the water. My father wept as the ocean pulled his arms as if to drag me beneath. He spoke the goddess into me and claimed my name. Alova, like the strong wave in a storm. And I would be dead before I proved my father a liar.

Although it would be easier to call it courage. To say that I fled my homeland, crawled across the ocean and somehow ended up in the Highlands because I was brave. Yet, the truth was seldom so easy to swallow. And the truth was that I now stood beneath a lord’s roof in a strange nation because my father had named me Alova, and I had already failed him once.

‘Alova,’ the lord called. My name on his tongue sounded like something on the verge of decay.

‘Yes, my Lord,’ I said in their tongue.

‘The fire is doing things again,’ he said.

I pulled down the apron and left the kitchen. The room where they dined echoed the storm and their silent glares. The lord sat at the long table beneath a flickering chandelier, nursing a cold broth. His sister slurped quietly beside him, and her son had long since given up on his spoon. I made my way to the fireplace and found the fire choking thanks to all the wood that had been piled on.

The wood was reluctant, but I dragged it away, and the fire sighed softly but refused to shake itself awake. I understood, I got tired too, and had those days when I would rather stay low and not wake. I gathered what remained of the firewood and whispered to the flames. I spoke low in the Mala of my people, and hoped the fire understood that I too knew weariness, that I too knew choking despair. I pleaded, and it yielded at last, stretching into a golden dancer.

‘Oh, look, the heathen and the flame are kin. How fitting,’ Lady Stounel said behind me.

Lord Stounel lifted his gaze to his sister then looked back down at his bowl. I stood at the far corner of the table clutching my hands over the weathered blue apron. Maybe it was the lady’s cruelty or maybe it was the tendency of storms to unearth the past, but I traced the threadbare seams and thought of my mother. Mountain born and brazen, she always had more pride than she was entitled to. It was a kindness that she would never see me in such clothes.

The boy was soon to bed. I had bolted his windows, and I listened for the creaking steel that barred his door from the inside. The lord soon excused himself to his study, which really meant his brown spirit. Only the lady and I remained in the vast room of billowy curtains and the table crafted for court, not a family of three. She sipped her tea and watched me, brown eyes brewing over the rim of her cup while I braced myself for the squall.

‘My brother is a fool,’ she spat. ‘What man keeps a savage for a servant? What man keeps a godless witch? Gods save us.’

The words were for me, without a doubt, yet she spoke them into the air around me as if someone else were there to marvel with her at such an abomination. It went on like this for a while. I watched her face. She was older than Lord Stounel by a moon death or three, but they looked to be an age. The boy was nine, and she had been young when she had him, but far too young still to be widowed. At five and twenty she had the bitterness of a crone. All I felt for her was pity, even as the venom dribbled down her chin.

The morning that followed was crisp and clear. The air was sweet as only after slaughter, and I pined for a harvest in Malajan. We would all be painted in the red of cow’s blood and river mud, dancing to the heavy drums of warrior arms on hide. The wind willed the song to high mountains, and the trees swayed when we asked.

The sounds were different here, but the air was sweet in its own way. Tobin and Daven milked the cows in the shed. They were stooped over stools looking about as old as the house itself. I had heard that once, this great house had been a castle, crawling with servants and noblemen. That the name Stounel had been strong and old. All that remained of it now were two hunched manservants, a lord who could not be bothered with his name, a lady with a broken heart, a savage, and a boy.

Back inside, I started fires for the lingering night chill and the ghosts. I set the dough for the bread and began chopping carrots and beets for their lunch. Food was easy in the West, all the dishes were variations of the same thing. Stew with bread, stew covered in dough, pie they called it but merely stew with bread on top and not on the side.

Cooking in the Seasones was a ritual, as was nearly everything else. The thought had only entered my mind when I saw a shadow over the table. The boy was never heard before he was ready to be seen. Had he been born in Malajan, they would have said he walked on spirits.

‘It’s far too early to be sneaking about.’ I tossed him a carrot. ‘If you can be up, I can be up,’ he said, only just nine but already as sharp as a shard.

The carrot crunched between his teeth, and I watched him sidelong. He had his mother’s hair, his uncle’s too, the brown curls nearly as unruly as mine. The blue eyes I had only ever known on him must have been his father’s. This was our morning ritual. I would make the food, and he would sit at the edge of the table in his nightgown with his legs folded beneath him.

I remembered the first time he had wandered in, a little scared, a lot more curious. He had pulled the chair and sat down with his back straight like the little lord he was.

‘Mother says witchcraft has burned all of the purity from your skin, and that’s why it looks like strong coffee,’ he had said. ‘Mother says the gods have turned their backs on your godless kin. That’s why you do not know how to speak their tongue.’

I had ignored him. One learns early in this new world that silence is the savage’s weapon. He had sat quietly for a while, hesitating between thoughts.

‘I do not believe her,’ he had said at last, climbing onto the table. I had stopped stirring and looked up at his childish face pulled into a thoughtful frown.

‘What do you think?’ I had asked him, when it seemed he did not know what to say.

‘I think …’ He’d been biting the inside of his lip in thought. ‘I think there are rabbits, and there are fish. There are big fish, small fish, red fish, and black fish, and silver fish. They all live in the ocean, but they are all different. Fish cannot walk like rabbits. Rabbits cannot swim like fish. What a silly world it would be if we were all the same thing. I think my mother underestimates the wisdom of the gods.’

I remember feeling utterly foolish for the tears that stung beneath my eyes. I had given him a carrot and asked if he wanted to hear a story just so I would have reason to turn away. I had told him of games that boys his age played by the shore. After that, he returned every morning with old questions in new words, and new questions of old things. Just as he sat that morning, nibbling what was left of his carrot.

‘Alova?’ I loved the way he said my name, like he understood it.

‘Yes, Rue,’ I replied, elbow deep in a mound of potatoes.

‘What other people are there in the Seasones?’

‘Many, many people.’

‘All of them Malajan like you?’

‘No, many different tribes. There are people of She, people of Zanshi, people of Aiian and many others.

‘They all have magics, like you?’

‘I don’t have magic, dear Rue. There are people in She that can move a mountain of rocks from across a river by merely staring at it. They have magic. Malajan have a little sympathy, is all.’

‘What is the difference?’

‘There are the old magics, the sympathies of three, the blood, the stone and the bone. People that have these like the stone throwers of She can command the things that the goddess granted them power over. The Malajan do not have this. We are warriors, the best there have ever been. We know the way of the spear and dagger, but the goddess gave us other small gifts. We can feel all things that have life in them. We can feel what they feel. We can hear them speak. We cannot make the wind blow us east, but we can speak to it, and ask if it may consider it.’

Ruben stared at me with those eyes as though the ocean were trapped in his sockets, like the last thing one sees before they leap to their death. I knew what he would ask. I had known for a while now.

‘Alova,’ he said, ‘I want to be a Malajan warrior like you.’ The boy was as stubborn as an old drunk. I told him that Malajan were not made but born into it. It was a song in our blood.

‘If that were true then you wouldn’t need to train. They wouldn’t have needed to teach you anything at all.’

He had an answer for everything, but some things were more complicated than words were capable of expressing. This would not do, I told him. We could argue until dusk, and nothing would change. Ruben stormed from the kitchen, stomped up the stairs, and then slammed his door in a rage.

The following morning, he did not come for his carrot, nor the one after, and the next. Soon, he would not look at me when we met in the halls, and I despaired slightly. Loneliness was sly. It crouched in the dark and waited until I was alone, then it leaped, grabbing me by the throat and rattling loose all those terrible things I had thought safely hidden away. I had been alone before, of course, but Rue’s company had left me spoilt and now, without it, I felt loneliness for the first time in an age.

~~~

- Shanice Ndlovu is a Zimbabwean writer. She was educated in part in Zimbabwe, and completed a law degree at the University of South Africa. Ndlovu runs a poetry podcast called the Poedcast, and has written numerous short stories in the genre of epic fantasy. She has been published in anthologies such as Botsotso and the K&L Prize. The Pride of Noonlay is her debut collection. She lives in Johannesburg and spends most of her spare time at the Johannesburg City Library, where she is a longtime member of the book club.

~~~

About the book

‘Ndlovu’s carefully crafted universe ushers in an engrossing fantastic journey. As the medley of charming characters stake their claim at a bigger, more adventurous life, they reach deep into all our secret yearnings and searing tragedies. Ndlovu skilfully intertwines her characters’ quests across the various stories, making The Pride of Noonlay an even more rewarding read in this regard, and this admirable debut will leave you waiting for more.’—Nedine Moonsamy

The stories in The Pride of Noonlay are crackling, lyrical, and controlled, and the worlds Ndlovu conjures are fascinating and vivid. This collection is a fresh contribution to African fantasy. Take a deep dive into stories of love, sacrifice, and loss—you won’t want to come up for air. Ndlovu’s voice is original, confident, and lyrically beautiful, weaving tales of humanity even in the strangest of circumstances.

‘Bittersweet sorcery, dark fates … set in an intricately imagined realm, these stories cast a sensuous spell. I was gladly magicked.’—Henrietta Rose-Innes