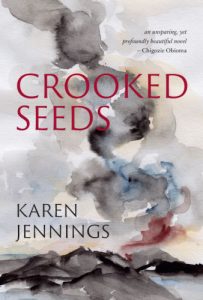

The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec chats to Karen Jennings about her new novel, Crooked Seeds, and making your reader’s skin crawl.

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: Before settling in to write these questions, I decided to read John Ashbery’s ‘Soonest Mended’, which you quote from in the epigraph to Crooked Seeds. It’s an excellent poem; it’s almost impossible to understand, but it leaves you with a sense of its meaning. It seems to describe the impossibility of living within mainstream society, and the impossibility of living outside of it. Why did you choose this quotation to open the novel?

Karen Jennings: Yes, it is a great poem—the rhythm, the flow. I must point out from the start that Crooked Seeds was begun a long time ago (2017, I think, or before) and completed more or less in 2021. In the midst of all that (December 2019) I ‘gave up’ writing ‘forever’ and threw away all my notebooks related to Crooked Seeds. A lot has happened since then, and I have written other manuscripts, so it is hard to answer questions with perfect honesty, since memory is fallible, and since the notebooks are rotting in a dump somewhere in Brazil. However, the poem conveys a hopelessness that I felt within Deidre—the sense that she didn’t stand a chance because she was planted crooked. How has she been able to grow properly, with the weight of her past—her parents’, her country’s, all weighing her down, pushing her over? I think there can be a similar hopelessness in our country—a struggle to grow straight and strong when we have been planted incorrectly.

The JRB: Your work has a tendency to darkness, but the first pages of Crooked Seeds really take it up a notch. I’d like to quote the first paragraph, so that readers can get an idea of the tone:

She woke with the thirst already upon her, still in her clothes, cold from having slept on top of the covers. Two days, three, since she had last changed; the smell of her overcast with sweat, fried food, cigarettes. Underwear’s stink strong enough that it reached her even before she moved to squat over an old plastic mixing bowl that lived beside the bed. She steadied her weight on the bed frame with one hand, the other holding on to the seat of a wooden chair that creaked as she lowered herself. She didn’t have to put the light on, knew by the burn and smell that the urine was dark, dark as cough syrup, as sickness.

It’s an extremely striking, visceral opening. What made you decide to begin in this way?

Karen Jennings: Beginnings come to me without any planning—I say that, but, of course, there must be things going on far back in the shadowy parts of my brain where I am not aware of them. Normally, the first page or so of a novel just comes out of me, almost as though I were possessed by a spirit, or muse, or monster. Those first paragraphs usually remain untouched or unedited, staying the same from rough scrawl to final, published manuscript. The rest of the novel is far, far harder to write!

The JRB: Crooked Seeds was longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and one of the judges said it made their ‘skin crawl’, while also calling it ‘brilliant’. Of course, every writer wants to be brilliant. But do you want to make your readers’ skin crawl?

Karen Jennings: In this case, yes. With Deidre, it was necessary for the reader to feel the extent to which she has let herself fall into misery and bitterness. Deidre could be all of us—we don’t like to admit it, but this is what we could become under different circumstances, if we allow bitterness to take over our lives. What one wants from a reader is for them to be haunted by the characters or story long after having read the book. Let them have the book under their skin. Let it make them think and make them interrogate themselves and the world we live in.

Years ago, I began reading Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the early hours of the morning. I read it in one go, finishing it as the sun began to rise. I felt sick, remained sick all day, maybe even for two days, just horrified and haunted by what I had read. That is what good writing can do to us—affect us viscerally, physically, take us out of ourselves and into something else in a way that is uncomfortable, even terrifying. In the same way, it can bring us into joy, love, tenderness. Good writing has the ability to change us.

The JRB: I’m sure many JRB readers will recognise themselves in that answer.

The novel takes place in Cape Town in the near future, and it’s recognisable—the mountain is burning, there’s a water crisis—but like a lot of your work the setting feels slightly unreal, a little uncanny, almost like a parallel universe. What do these unmoored geographies offer you, as a writer?

Karen Jennings: Is it unmoored? This is Cape Town, slightly reimagined, but only minorly. How many communities around South Africa are already in situations where they have to queue for water, or find taps completely empty for weeks on end? How many communities continue to be forcibly removed, their homes bulldozed to the ground? Yes, one can argue there’s context and semantics and blah blah. I don’t see much difference between the world of Crooked Seeds and the way many people live in South Africa today. Isn’t that part of the horror of it? How real and imminent it can seem?

The JRB: True. Perhaps I’m an optimist, or a denialist (I do live in Joburg, after all). I listened to a conversation in which you mentioned that for you the scarcity of water in the novel reflected South Africans’ ‘thirst’ for things to get better, and how we feel so ‘parched’ by our history. Could you expand on this idea a little?

Karen Jennings: My worst nightmare: being confronted by my own words! A few days ago a first-year student of mine came up to me and said she and her friend have made a Powerpoint presentation of ‘things’ I said in lectures last semester. At first I didn’t understand. Yes, okay, you made notes, fine, that’s what you’re meant to do. Then I caught a glimpse of her phone, on which she had one of the slides from the presentation. It said something ridiculous like ‘It makes me feel like my arms are in the sky.’ Something nutcasey like that. I have yet to see the rest of the presentation—she threatened to email it to me—but can imagine it only gets worse after that.

To answer your question—aren’t we all thirsty for a better South Africa? Has the ANC government quenched that thirst in the past thirty years? And this GNU? And now with these Mkwanazi allegations and a response from certain ministers that what he is doing is tantamount to a coup.

This past Friday, Mandela Day, my friend who works for an NPO that helps to run the Asivikelane campaign (which helps communities to empower themselves by informing governments and municipalities about inadequate services), went to RR Section in Khayelitsha, which was flooded and filthy due to the Cape’s winter rain. But what they specifically went to see was not the way citizens are living in flooded homes, but rather, the way community plumbers have been taking care of and fixing standpipes and taps in the community. Without these volunteers, nothing would work, they would have no running water because the inhabitants have learnt to have no hope in the government ever doing anything. My friend said it was like a gut punch—but a gut punch that we need. Yes, we all need that gut punch, but who needs it most—the people in power. They need those gut punches every second of the day until they wipe out corruption and start paying attention to and caring for the people they claim to represent.

The JRB: At one point, Deidre’s neighbour says to her:

‘Every time I think I’ve seen the worst of you, you come out with something even more terrible. Every single time, no matter what. Are you trying to be unpleasant, tell me? Is that your plan, to be unpleasant and make everyone dislike you? I really want to know.’

And Deidre responds: ‘No. It’s just the way I am.’ Many people are put off by ‘unlikeable’ characters, and I couldn’t help but imagine a similar exchange between you and a reader. What do you hope readers take from encountering a character like Deidre?

Karen Jennings: [Laughs] So I am unlikeable, unpleasant, and rude? Thanks, Jen!

The JRB: Oh my god, no! I meant I could imagine a reader confronting you about Deidre’s ‘unlikeability’ …

Karen Jennings: To be fair, I have recently found myself settling into middle age and becoming quite grumpy, even though, to a certain extent, I am more content inwardly than I have ever been in my life.

But enough about me. The book and Deidre. It is tricky to give a succinct answer here. There’s the haunting or visceral experience I spoke of before. There’s the fact that we might all become or have been some form of Deidre under different circumstances. But there’s also the delicious complexity of being human—Deidre is awful, awful, awful. Yet we feel pity for her. She isn’t just bitterness and rudeness. There is a lost, lonely, frightened person inside her too. This was the tricky part—making the reader both dislike and pity her.

The JRB: And where writing is concerned, how do you develop and maintain the voice of a character like Deidre? Could you talk us through that process?

Karen Jennings: As with any writing, the process is simple in theory, very hard in practice. The process was: many, many, many painful rewrites. Draft after draft after draft. For example, I was right near finishing, but knew I needed just one more sentence somewhere in the book (I can’t remember where now). I knew that paragraph needed one small, simple sentence, but the words wouldn’t come. I cried and cried and felt dreadful emotional pain because I couldn’t do it! Eventually I phoned my close friend, who also happens to be my publisher and editor, Robert Peett. He spoke to me calmly, talked me through it, asked what in the simplest sense I needed the sentence to do. I think it took an hour, but he helped to calm me down and to help me find the words I needed.

That is how important the right words are. Without the right words, one has failed, which is a devastating feeling.

The JRB: You often use a complex, intense person as a subtle, almost stealthy way of scrutinising broader issues. It seems, for you, that character and theme are tightly woven together and impossible to separate. Would you agree?

Karen Jennings: Very much. I am certainly character driven, rather than plot. In fact, my writing has very little plot at all. It is far more to do with the way in which the internal world of the character engages with the external world.

The JRB: As Deidre is forced to reckon with her family’s dark past, the country is reckoning with its traumatic history: literal and figurative excavation. But I wouldn’t call Crooked Seeds an allegory. Rather, it demonstrates how trauma can be contagious, and how hope survives even the bleakest of times. At the end of the novel, Deidre defies her own cynicism with a wish: ‘If only the rain would come, just a little bit of rain, to wet the soil, feed the seeds, so that something might grow again.’ I’m not sure what my question is here, but perhaps it’s something like: how do you capture a moral truth while avoiding generalisation?

Karen Jennings: This isn’t an easy question to answer. Just as I knew the first paragraphs, I knew the last lines. They just emerge, without effort or thought. I can’t say more than that without starting to sound pretentious, giving opinions where I have no clear ideas.

The JRB: Your work is deeply, even viscerally South African. But you have spent quite a lot of time outside of the country. Do you think you could write a novel set somewhere else?

Karen Jennings: Only if it were about a South African being in this other place. There is too much history and culture that must be known to write well and authentically—I couldn’t write a book and feel good about it if I didn’t feel a strong sense of lived knowledge (not researched knowledge) about a place.

The JRB: I’d like to ask you an industry question. You have spoken before about your struggles to get your work published. After being nominated for and winning some major literary awards, and achieving international recognition, has the process of publishing your work changed?

Karen Jennings: Not at all. I am still being rejected left and right. My books don’t make enough money for publishers. It isn’t worth the risk—especially at a time when the industry is in crisis. It hasn’t made an ounce of difference, that’s the truth of it. I am happy to remain with the small or independent publishers who are loyal to me and to whom I am loyal.

The JRB: Can I ask what you’re working on at the moment? What can we look forward to?

Karen Jennings: A number of things. One, a poetry/prose book coming out at some point before the end of the year. It is set in the eighteenth century on the Cape’s northern frontier and tells the story of real-life father and son, Swartbooij and Titus, who were integral in beginning a war between colonisers and the local Khoesan; two, in mid-March my new novel, First of December, is coming out. It is set in Cape Town in 1838 in the week before the emancipation of the slaves; three, I am working on a novel—struggling terribly with it—set in Cape Town in the present; and four, I’m working very slowly on a biography.

The JRB: I’m sure we’ll catch up again next year, then.

~~~

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor.