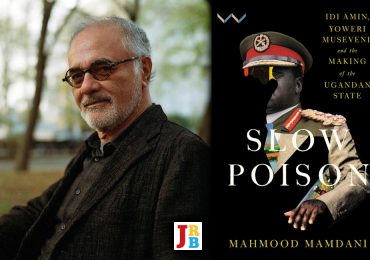

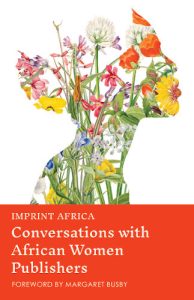

The JRB presents an interview with Ellah Wakatama, facilitated by Joel Cabrita, excerpted from Imprint Africa: Conversations with African Women Publishers.

Imprint Africa

Edited by Joel Cabrita

Modjaji Books, 2025

‘I want to be in the business of making culture.’

In conversation with Ellah Wakatama

10 February 2021

Joel Cabrita: Could you begin by speaking to your early life and reflecting on some of the influences that you feel have shaped you? Specifically, what resulted in your commitment to African literature?

Ellah Wakatama: I was the child who read underneath the covers with the flashlight after lights out. I was also the child who hid up in the tree so my mother couldn’t find me and tell me to wash the dishes. It has been my whole entire life, and I think that’s a story that many publishers will tell you, that they are readers first and foremost. I think I have one early experience—two early experiences—that have to do with language that are really formative, and as I get older, they get more and more important with time. The first one is that I didn’t speak English until I was five years old. I’m the second born in my family and I lived with my grandparents in a village in Zimbabwe from infancy until I was five years old. At that point, my dad was invited onto the Iowa writers’ programme. After a year, they decided to bring the whole family to the US, to Iowa. I arrived in Iowa very much a village girl. I didn’t know anything and did not speak any English at all. My mother says that I ran to a group of Black children and of course if you’re Black, obviously you speak Shona, because Black people speak Shona. I spoke to them and they did not respond to me. She says that for six months I didn’t talk, and when I did start speaking, I had a stutter.

My speech therapist subsequently read Narnia books to me. I don’t know if any of you have read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe? To me, those books were a place of refuge and healing and a place of adventure. The college my father was then studying at was Wheaton College in Illinois and they owned a wardrobe that had belonged to CS Lewis. My fourth-grade class was going to visit this wardrobe, so I wore my daisy print raincoat and I had sandwiches, a flashlight and everything, because I was going to Narnia and not coming back. So, of course, when the door didn’t open, that was fine too, because there were other kids around and obviously the doors to Narnia couldn’t open because the other kids did not know about it. Besides being the trippy kid I was, I think that the experience of reading those books was really fundamental to me, because that series of books did so much for me. It gave me language and also taught me the potential to be elsewhere and to travel through books. So, I think that’s my foundation, my origin story.

Joel Cabrita: I certainly grew up reading the Narnia books and I saw some of the others in the class nodding as you were talking about them. In your answer you touched on something that we’ve discussed quite a bit in class, which is the issue of language. I read in an interview you gave elsewhere your account of the trauma of being uprooted and moving to a country where you did not speak the language, and no one understood you. Could you reflect on the significance of language, and especially African languages, for you in your work? Obviously, there’s a long-standing debate about what language African writers publish in, whether it’s an indigenous vernacular language or English, French or Portuguese.

Ellah Wakatama: It’s such an important discussion. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, whom I adore, and his son Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ, who is a wonderful scholar himself, speak a lot about writing in your own indigenous languages. Now, my dad was a Shona language novelist early in his life. The preservation of language is really important. Many of you on this call speak another language. There are some things you can say in your mother tongue that don’t quite translate to English. I don’t know if you have this experience, but I’m a different person in Shona. I’m not quite the same person that I am in English. I think that to preserve all of those emotional states or states of relationship, we do need to preserve language, but only a certain number of people are going to read books published in these mother-tongue languages. But it’s still essential to preserve and valorize them.

The English that I speak in Zimbabwe is very different to the English that Bena’s family in East Africa will be speaking or Barry or Rachel or Kyle. Not just the accents, but the way that we use the language is informed by that mother tongue. And for me as a publisher, I want to bring that experience of English as ‘another language’ to my readers. For a long time, Indian writers for example, were considered foreign here in England. But there was a time maybe twenty to twenty-five years ago when Salman Rushdie and others were writing and Indian English became something that readers all over the world took for granted. We knew what it meant. If I say to you ‘Congratulations to Kamala Aunty’, whoever has read an Indian novel knows that putting ‘aunty’ after somebody’s name is what you do, right? It becomes familiar. Or if I say to somebody who is West African or has read West African fiction, ‘Ehn!’ you know exactly what that means.

All of those things start being familiar if we allow the idiom and inflections of those languages in the works that we publish, and so my job as a publisher is to find the best way to do it. To give one example, I do not italicize indigenous languages in any of the books I publish, because those italics tell me that the standard is English and the rest of us are deviating from that. Just as the standard is too often white and male and the rest of us are some kind of deviation. A writer called Nii Ayikwei Parkes taught me this in my publishing of his book, Tale of the Blue Bird, because he was insistent that the only things that would be italicized were the things that were being said or thought in English, the rest of it we had to assume was either Twi or Ga, both of which are Ghanaian languages. That’s a challenge for the reader, but it’s also an assertion that the centre of my world is going to be where I say it is, not where the Western canon has already said it is. And that is the power you have with something as small as whether I use italics or not.

Joel Cabrita: I love that example of how the reverse use of italics can effectively decentre English as the normative, universal language. As a personal side note, I had a chapter in a book published recently by Wits University Press, one of the big academic publishers in South Africa, and I made a case of not having italics for isiZulu words, and my request was turned down on the grounds that it didn’t meet their style sheet. So what you’re doing with your writers is pioneering. For my next question, in thinking about the long sweep of your career and all the changes and developments you’ve seen as a publisher and editor over the years, can you speak to what you see as the trajectory of African writing, both in fiction and in creative nonfiction? We know there’s been a recent resurgence of interest in African writing; what do you see as being the major shifts in the publishing world?

Ellah Wakatama: So, the two things that excite me the most are creative nonfiction and genre writing for African writers. People will talk about the grandaddies and some of the grandmothers of African writing, these are people who were writing largely in the nineteen-fifties, really important to most of us and their words are still relevant, but their work is very literary fiction. I’m the daughter of someone who was more of a commercial novelist. My dad used to write accessible, commercial novels. Novels with pacy plotting and relatable themes. As a result, I’ve always been interested in the publishing of commercial literature that has the potential to reach a wide audience. Because for ‘literary fiction’, only a small number, maybe a tenth of the population, is reading at that level, which is fine because that’s how we build cultures, but I also have long wondered about the crime novels you buy in the supermarket. I want to publish Black writers, African writers, writing those crimes set firmly in Nairobi or Johannesburg or Addis Ababa. That change has been coming through only in the past ten years. You see more science fiction, not quite enough romance genre yet, but all those things are bolstering literary fiction writing.

I think that wide range creates volume in the landscape, and the more African writers are writing across the board, the more writers are going to make a living out of their work, which happens most, realistically speaking, in commercial publishing. The international publication of African writers is not because the publishing industry suddenly woke up to talent that has always been there in abundance, it’s because of a select number of writers whose work broke out, making money, and so something like Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi or My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite, if books such as these start making money, then publishers want to replicate that. And so, it’s one example of where the commercial impetus is really feeding a diversification of our reading experience in a way I find exciting.

And with creative nonfiction, I’ve taught courses with a dear friend and writer, Mark Gevisser. About five years ago, we became really concerned with the lack of opportunities for African writers, especially those living on the continent, to get their creative nonfiction published. For a good period of time, I was Deputy Director of Granta magazine, and we would commission long-form pieces and pay a substantial fee for the writer to go off, travel, do the research, and so on. That kind of deep investigation, long concentration writing takes money. And very few writers who have to make a living doing other things have that. So we taught a two-week course in Uganda on creative nonfiction. As a reader I am tired of hearing what old white men have to say about the rest of us—I’m directly quoting my nineteen-year-old complaining about her university courses. I thought she put it really well! What would happen if you’re writing a story about immigration, for example, and the writer thinks of the continent of Africa as being international but only within the continent, so ‘international’ doesn’t mean London or New York or San Francisco. International means in between Accra and Addis, Harare and Gaborone. What happens there? When you want to write about Ebola, what happens if you ask a Sierra Leonean crime writer who is also a forensic pathologist, to write the piece for you? What do you get that you would not otherwise? This was the approach I took with Safe House: Explorations in Creative Nonfiction that resulted from this nonfiction initiative. And that was exciting. I had no particular theme in mind, I just said, ‘I like your work, we’re going to give you a wad of cash and this much time. Pitch to me, tell me what you want to talk about.’ Some of the writers travelled, some wrote quite personal pieces, it was a whole range. Out of that, other initiatives have added to what I think is a really exciting growth in creative nonfiction on the continent generated by writers themselves finding money to put things together. We can all only benefit from that.

Brittany Linus: I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the Afro-fantastical and Afrofuturism as a genre. Have you seen any fiction works written in that vein? What sort of impact will Afro-fantastical work or Afrofuturism have on the continent?

Ellah Wakatama: I often have trouble with definitions, especially with the whole Afrofuturism thing. I know it when I see it, but it’s hard for me to define. I am a fan of speculative fiction; I always have been. I haven’t always been able to work on it because I’m primarily a literary fiction and nonfiction publisher. One of my jobs right now is commissioning an original fiction full-length book for Audible. When they asked me, I said I would do it if I could do genre. Science fiction is something that I’m doing and I’m also making sure that I am commissioning African writers to write science fiction. I have one non-binary writer based in the west coast of the UK of Nigerian origin. I have a white South African writer writing science fiction for me. I have a Brazilian–American Black writer writing another science fiction novel. So in the next couple of years, my hope is that my list of Afro-speculative fiction will come alive. If you look at short stories, there’s a lot of amazing stuff right now. Also, think of the wealth of untapped material we have. Think about Yoruba culture or Voodoo in Haiti or Candomblé in Brazil, and all the other African religions that haven’t yet been written into speculative fiction, let alone concerns of language and folklore and the primordial soup of speculative fiction. Science fiction and any sort of futurism are really good ways to find innovative ways to think about the now. I don’t know if you’ve come across Tade Thompson? He’s one of my favourite science fiction writers. Mighty, mighty guy. He wrote the Rosewater trilogy.

Joel Cabrita: On this topic of expanding the genres of African writing, and this greater interest in commercial popular literature, we’ve also looked at the Pacesetters novels of the nineteen-seventies in our class. It was great to hear from Barry Migott and Anita Too about their perspective of the novels. Both of them grew up in Kenya and grew up reading these novels for fun. We thought about how this really significant genre—in terms of the number of people reading these paperbacks—goes under the radar, not classed as ‘respectable’ literature despite being so influential.

Ellah Wakatama: Yeah, and it’s almost like a gateway drug. You start there and next thing you know … [laughter]

Joel Cabrita: As you know, this class focuses not only on African writers and the publishing industry in Africa, but also specifically on writers who identify as women. In your comments about the influential generation of writers from the nineteen-fifties, you referred to the grandaddies and the very few grandmothers of African literature. Can you speak to gender in African fiction and nonfiction at the current moment?

Ellah Wakatama: If you consider the obstacles that women and African women have faced in terms of writing a novel and then think that we can still name Bessie Head, we can name Doris Lessing, we can name Mariama Ba. The fact that I can come up with these names that just roll off my tongue is evidence of the massive willpower of these women. And then it also makes you think about those women writers who never quite made it to that point. For example, Tsitsi Dangarembga, who is still alive now. She was the first Zimbabwean woman to have a novel published, and she’s now only in her late fifties or sixties. That’s pretty astonishing. I don’t necessarily think it was about keeping them out, but access was a problem. And it always has been. Even when I started working, it was a problem for African writers and African women. The question is, where do I send my book? I don’t know any editors or publishers. How does this even work? For a long time, even now, it’s been made so difficult to reach that point. If you’re the first person in your family to be able to read and write, or the first person to have an education beyond primary school, then where are you going to make those contacts? Breaking down those barriers to access has allowed us to take advantage of the real talent that is available. It’s all about volume, really. The numbers of African women writing has grown dramatically.

I am now becoming concerned about the state of access to publishing for men of colour and for queer writers of colour. We could all name ten African women writers, starting with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. There are just so many African women—I think of Maaza Mengiste—who are selling on an international level. It is much harder to find the same volume with Black male writers or queer writers. It is something that is starting to be addressed, but for me it’s an important area of focus. I reckon that if you are telling the story of our times through the point of view that leaves out queer writers and leaves out gender-fluid writers of colour or leaves out Black men, then our story is not complete. I think that these things are—and I don’t want to sound glib—easy to fix. You know what’s lacking on the bookshelf. At least for me as a publisher, if I think there’s something lacking, then it is my job to fix that. It is about knowing that you, as an acquiring commissioning editor, have the power to say, ‘This is what I am looking for’, and ‘Let me help you amplify your voice’.

Olayinka Adekola: You’ve described how there’s a lack of queer African voices in the literature sphere. I also know that often homosexuality and queerness are very taboo. How can you work around that as a publisher to produce this work that needs to be heard? Also, how is it received?

Ellah Wakatama: Fab question, huge question. There is a lot more writing from queer writers and gender fluid writers and trans writers because we are in an era where people are defining themselves and demanding to be called by their names. And not just in Western countries. I think that one of the great misconceptions is that all Africans are homophobic, and all Africans deny any kind of non-binary gender identity. If you look at traditional African societies, every single one has a way of accommodating those of us who are different in that respect. Yet, mostly because of religion, both Christianity and Islam, we have leaned towards a fundamentalism that is very much based on a Western conception of gender binaries. So our ways of living as people are now forgotten. A lot of writers who I work with are wanting to give voice to the fact that certain sexual identities are not Western but can be deeply rooted in African culture. I’ll mention Akwaeke Emezi, for example, who is non-binary and writes very much from their own traditional cosmologies, both as a Sri Lankan and a Nigerian.

And there is the very real fact of danger for people, either publishing or writing about these issues around sexuality and identity. In some countries you can get killed. One, as a publisher, has to be very sensitive to the fact that it may just be controversial in a Western country but in another country, it is a matter of life and death. Care for your writers is really important and you have to be sensitive. At the same time, people within those countries are fighting those fights themselves. It’s not as if activists are waiting for a Western publisher who swoops in to save the day. I have publishing friends in Uganda, in South Africa, in Kenya, who are all working to fight those battles. What’s exciting is that these developments make for a whole genre that is melding an understanding of who we are as people with issues around human rights. It can make for really beautiful fiction, great poetry, and life-changing creative nonfiction.

~~~

Ellah Wakatama is an editor-at-large at Canongate Books. She is chair of the Caine Prize for African Writing and served as a judge for the Man Booker Prize in 2015. She was founding publishing director of The Indigo Press, series editor of the Kwani? Manuscript Project and has edited the anthologies Africa39 (Bloomsbury, 2014) and Safe House: Explorations in Creative Nonfiction (2016). In 2011, Wakatama was awarded an OBE for service to the publishing industry and in 2018 she was made an honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

~~~

Publisher information

Imprint Africa: Conversations with African Women Publishers is a collection of interviews that chronicles the work of a new network of female intellectuals and activists who have transformed African publishing across the twenty-first century.

The rise of woman-led literary initiatives across the last two decades—from Blackbird Books in South Africa to Ake Arts and Book Festival in Nigeria—has led to major literary-publishing shifts. Bringing together voices from the African diaspora and the African continent; these conversations speak in vital ways to the successes and challenges of this ongoing and transformative literary moment.

The book includes a foreword by Margaret Busby, an introduction by Joel Cabrita, of Stanford University, and an afterword by Kadija George Sesay (Sable Literary Magazine).

There are interviews with nine women publishers/literary activists: Ellah Wakatama (Caine Prize), Bibi Bakare-Yusuf (Cassava Republic Press), Zukiswa Wanner (Paivapo), Ainehi Edoro (Brittle Paper), Louise Umutoni (Huza Press), Lola Shoneyin (Ake Arts and Book Festival), Colleen Higgs (Modjaji Books), Goretti Kyomuhendo (African Writers’ Trust) and Thabiso Mahlape (Blackbird Books).