The JRB presents new short fiction by Yanjanani L Band, which emerged from the Caine Prize workshops, excerpted from the 2024 Caine Prize for African Writing anthology, Midnight in the Morgue.

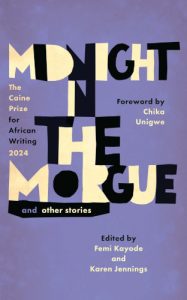

Midnight in the Morgue: The Caine Prize for African Writing 2024

Edited by Femi Kayode and Karen Jennings

Jacana Media, 2024

Too Long for Home

Yanjanani L Banda

It is the news of your younger sister’s sixth pregnancy that sets everything for breaking. You are just from work. Your handbag, a purple Chanel knockoff, along with your kaunjika high heels and the eight-inch monstrosity of a hair piece line your way to the kitchen where you guzzle a cup of tepid tap water amid laboured breaths. Freedom at last. Until your mother’s call comes in. Right as you scratch at the itch on your ample behind, your mind on the dinner you are yet to put together before your husband walks through the door.

‘Your sister has done it again,’ she says, and you want to ask what, but hold your tongue. The mixture of excitement and disapproval in your mother’s voice reminds you of two years ago, when she called to announce Nelia’s fifth pregnancy. You feel the distance between you constricting. Her words charge across the invisible cell phone lines like a suffocating tornado, displacing the calm you had anticipated for your long weekend ahead.

‘That girl—tsk! I told her I would not tolerate this behaviour, but did she listen?’, she says, adding fuel to the fire already burning in your chest.

Your eyes roll of their own accord. You can tell her playing at disappointment has improved with the years. Even with the exaggerated sigh, you can picture her smiling, shaking her head in disbelief for good measure. Your tongue itches to silence the rehearsed theatrics.

Only when talking to you does her voice take on the tinge of reproach. Perhaps letting you know she is trying to be a mother in her own way, so you do not feel too deprived of the warmth that should have existed between you. But you know it is your monthly support that makes her act the disapproving mother. Nelia is her baby. The one who stayed. It absolves her of any missteps in your mother’s eyes.

And you? Well, you bear the weight of your father’s sins against your mother. You are your father’s daughter, after all. The one he carried along in his carousing. And certain sins, however polished, have a way of shining even brighter behind their manicured exterior.

‘Who’s the father this time?’ you ask, careful to hide the animosity in your voice. You succeed a little, but the edge is there, wrapped in the questions you dare not vocalise. Why not me? Your good deeds and six years of marriage have not smoothed the folds of your shrivelled womb where a seed should pucker to life and grow.

Your mother prattles on. Short, successive bursts that bleed into one another, barely registering in your mind. For once, you wish she would remember you are her daughter too—that your sister’s fertility mocks your own lack of fecundity. To force your enthusiasm feels inhumane.

You do not say these things out loud. For even to your ears, the words seep with an envy uncharacteristic of your curated front. You have worked too hard for the space you now occupy in their hearts and minds, however small. Instead, you clutch at the burning in your chest and nurse the saltiness that trickles into your mouth.

Good daughters hold their tongues, you remind yourself. Good daughters do not take a life. At least, not one so close to them as the one you snuffed out.

***

There was nothing eventful about your birth, you have been told. You greeted the world on a Monday morning. Bright and early, without a fuss, as though privy to your father’s impatience to leave you and your mother behind. And leave he did, after holding you in his strong arms and bestowing upon you a good name.

You were meant for consolation.

In the years of your father’s absence, you were a reminder of both joy and pain to your mother. When the sting of abandonment overwhelmed her, she would pinch your high cheekbones and only fell short of gouging out the eyes you had inherited from your father.

She had fallen for the sincerity in the depths of your father’s eyes once upon a time. A sincerity she had not known was only temporary, masking your father’s impatience to conquer his prize.

You cried with the pain she induced even as you ran to her for comfort. She curled into herself at your touch, sometimes swatting you away from her side. The anguish in her eyes was something you did not comprehend. To you, she was Mama, and that was just the way of love.

When joy descended upon her, your mother would whirl you around in her arms, planting noisy kisses on your cheeks, eliciting squeals and childish laughter. It was a happiness of its own kind—a well many inches deep, yet leaking on the sides. Mother and daughter playing at dissociated lives, but you did not know this then.

Your father returned when you were five years old, a smile on his lips. He was a tall, handsome man who put beauty to shame with a mere gaze at his frame. He walked through the gate of your M’chesi home that Saturday afternoon like a man who owned the world, raising dust under his feet. It was your mother’s gaping mouth and fixed gaze that drew your attention.

He stood there, all limbs, with an intensity that made the wind stop to listen. He crouched and beckoned to you with his open arms. For a moment, you stood in place, staring between him and your mother, searching for confirmation in your mother’s distorted face. She nodded lightly. Visible enough that you knew you did not imagine it.

You took slow steps towards him, turning to your mother again and again, waiting for the moment she would bid you to retreat. Even as she urged you on, her face wore a look you could not decipher. It was fear, pain, and relief rolled into one. When you were at arm’s length, your father plucked you from the ground and threw you in the air. You landed back in his arms. Too quick. Too soon. Like the distance between you had never existed. Like he had never left.

You laughed cautiously at first. And then heartily. The little cackle that made everyone within earshot smile. He laughed too, and it was beautiful to your ears, like the beating of a drum with its accompanying echoes. It was that laugh that warmed your mother’s insides. Made her head hang in surrender to his buttered words as he promised to love her better.

‘I need you,’ he said, your muddy body plastered to his chest as though it were a lifeline. Your mother softened at how you patted his cheeks and giggled at the prickliness of his sparse beard.

He must have seen her smile right then, as she watched you bouncing in his hold with childish pleasure. He studied her like a hawk. And true to the man he had always been, he shortened the distance between them stealthily, still cradling you in his arms. He reached for her hand slowly, but held it tightly once he had it in his grip. Like one who would never again let go. Once again, she dared to look into those eyes. Deep brown eyes with the calm of the sea, the brewing storm underneath hidden perfectly. And once again, it would be to the undoing of you all.

For a while, your mother believed he would stay. That he had tired of a life without roots burrowing deeply into the ground. He had always been a son of the streets, playing house to tame the animal inside.

Eager to keep him, she cooked and cleaned and bent to his whims. Two years he stayed, teaching at the primary school which was always desperate for learned men. And on the day Nelia came along, your mother left you in his care. You were her insurance. She imagined he would not leave you alone in her absence.

Your mother knew you had become his world. The one whose babbling pried laughter from the recesses of his soul and brought a shimmer to his eyes, illuminating the handsome dark face she had fallen in love with many years ago. You rode on his shoulders or walked hand in hand with him as he kept pace with your small strides. Sometimes, she caught him watching you, a contented smile clear on his face. For you, he would chase happiness to the depths of the ocean or the peak of Sapitwa. For once, she believed him a changed man.

As she wailed and pushed Nelia into the world, your mother tucked the fear that threatened to undo her deep in her chest. If not for her, he would stay for you. But when she walked into the two-bedroom house a few days later, her stooping grandmother cradling Nelia in wiry arms, stifling silence greeted her at the door.

He had done it again. This time, taking even her insurance plan with him.

For days, your mother refused to hold Nelia, her sorrow mingling with crazed laughter. In the mornings, she sat on the verandah, staring at the front gate, willing him to reappear, wishing she had loved you better. At night she whispered into the silence, proclaiming on him a thousand deaths even as she prayed that he would return you into her arms.

He did not return, so neither did you; all her waiting and searching yielded nothing.

Once again, she loathed the sincerity she had spied in his eyes on the day he reappeared. Now she knew better. His sincerity had not been meant for her. You had been the prize all along.

***

The woman with the gap teeth and skin rich with the sun’s warmth was the first of the many you remember. For months, she bathed your body in scented lotions and mothered your stomach with succulent meats enticing to your seven-year-old eyes. She had learned quickly that you were the door to your father’s affections—and had accepted it. Until a year down the line.

You lounged on the worn leather grey couch mirroring your father who sat comfortably on the opposite sofa as though he owned the place. Tom and Jerry played on the screen, their murderous antics diverting your gaze once in a while. The woman sidled close to your father, brushing his arm the way she did when she wanted something. She stole wavering glances at you before launching into her desperate pleas.

It was his pronouncements of love she wanted, and he gave them noncommittally. Until she begged for the one thing she should have never dared to ask.

‘Tell me you love me more than her,’ she said, gesturing at you with skittish eyes.

It was the first time you saw your father’s eyes bulge in anger, his nostrils flaring as though gasping for breath. The first time you witnessed the marks your father’s hands left on a woman’s body. Though you wept for the mothering touch you would miss, you learned the most important lesson about your father: the pleasures he sought in a woman’s embrace were nothing compared to the place you occupied in his heart.

She was the only woman you had loved outside of your mother, so you promised yourself never to love your mother’s replacements again. Instead, you broke their expensive perfume bottles, burned favourite dresses, threw car keys in the trash, and made loved animals disappear, hopeful that, with every indiscretion, you drew closer to returning to Mama. You bore the battle scars of the women’s anger on your body proudly. But even after replacement number seven, you were not returned to her. It was just you and your father again. You were now fourteen years old, learning to live with the marks your father’s hands had started to leave on your body. In this, you were loved and unloved all in the same breath.

***

‘How is this so hard to understand!’ You throw the wig that was clamped in your fist to the floor, the distance from one end of your bedroom wall to the next feeling too short for your pacing. ‘I wear all this cheap stuff just to take care of them. Forget buying myself a new pair of shoes. And what do I get in return? Do my sacrifices not matter? Shouldn’t they matter to you at least?’

Maziko sits upright on the bed, staring at you through sleepy eyes as you re-tie the chitenje around your bosom. You have not slept since your failed attempt to talk through your angry tears the previous night. Your eyes are still red and puffy from the effort.

‘Self-pity does not suit you,’ he says, and you wish you could take a dagger to his chest.

Maziko reaches for his cracked Tecno on the weather-worn stool you purchased a week before your wedding at the second-hand store you had patrolled for months after you and Maziko had agreed to marry.

‘Can’t we do this in the morning? You know, when we don’t have to wake our neighbours?’ He gestures to the switched-on light from your neighbour’s bedroom window.

His voice is soft. Placating. He has never been one for a fight. He’s a soft-spoken man, your Maziko, a man of peace. But today, it raises your ire. You wish for a hint of your father’s cruelty in him. The thing that made him cut ties swiftly and efficiently.

‘No,’ you hiss.

There’s an urgency in your voice. A spurring on you do not wish to die down. You have been at the mercy of your sister and mother for sixteen years. Believing, with every good deed, you cancelled your father’s debt to them. Your debt. But with each passing year, you have felt the noose tightening around your neck.

When the first child came, you agreed it was a mistake. That you would do your best to care for them on your secretary’s salary. Two years later, Nelia was at it again. You protested this time and spoke firmly so it would not happen again, calling on your mother to exact some discipline. It was to no avail.

‘You should have modelled better behaviour to your sister,’ said your mother. ‘But how could you, when you were not even here for her?’

You had been too dumbfounded to ask how Nelia’s misbehaviour was your responsibility. And with your silence, you had signed off on everything that followed.

You stop short of the other wall and turn to stare at Maziko whose eyes have followed you in your nervous pacing.

‘I can’t wait.’ Your eyes are pleading, but there’s a cutting edge to your voice.

‘OK.’ He raises his hands in surrender, patting the space beside him. ‘Then sit down, at least. I’m on your side. You know that, right?’ he says, and you wonder if nothing would change if he knew.

You wonder if he would look at you the same way. If he would stay. You have beaten yourself up about it for far too long. Two thousand six hundred and fifty-five days to be exact. You wanted to be loved. When he came along, he cared for you in a way that erased everything that had gone wrong in your life. Everything you had done wrong. With each passing day, it grew harder to own up to the part of you that you feared he could never love.

You steal a glance at him one more time and let out an anxious breath. He should be the first to know. Freedom must come at a price.

‘No, I’ll stand. I’m too anxious to sit.’

He nods and rests his folded hands on his crossed legs. You rub sweaty palms on your hips, leaning against the wall. Your tongue feels heavy in your mouth. You can feel the twitch in your upper lip as the air between you solidifies. Finally attuned to your own racing heartbeat, you begin to speak.

***

Your father kept souvenirs from all the women he left behind: a necklace here, a bracelet there, a picture, a scarf, a ring, and many other things you did not much care for. Each bore a tag with the name of its owner scribbled in meticulous calligraphy by your father’s hand. The conquered, on display. A museum of bodies worn and destroyed. Your mother’s name was not among them. There was nothing of hers to hold on to.

***

You remember it like yesterday—the day your anger calcified into a tangible thing. You had just taken a ferocious beating to your side from your father’s belt.

‘Why do you make me do this?’, he asked in that soft voice that always made your skin crawl. He was a different man on such days. Transported back into his street-roaming years. When only ruthlessness guaranteed survival. And you had to survive, just as he had.

The gag in your mouth ensured that the only thing you could do was grunt. You had to keep up appearances, both of you. To your neighbours, you were a father and daughter left behind by a scornful woman. You played your part, clinging to the hope that one day he would release you back into your mother’s arms just as he had promised the first time he left belt marks on your skin.

He often told you he knew of your little schemes to get him away from the women who had made both your lives easy. He told you the belt was a witness to both his love and disappointment in you.

‘We were supposed to be happy,’ he said, tears running down his cheeks. ‘You made me want to be a better father, a better man. That’s why I took you from her. Because I wanted to be good.’ He sobbed like a child.

Every time those tears fell, you wanted to believe him. To believe that you had hurt him much more than a daughter should. That if you had endured, if you had not tried to get him away from your mother’s replacements, you would have had more of his love and less of leather scalding skin, leaving welts mapping every part.

You crawled on your other side. Each effort made your body shudder with the pain. You froze at the door’s threshold when his bloodshot eyes finally registered your retreat.

‘You shouldn’t have behaved like your mother. She thought she could save me.’

He closed his eyes, deep in contemplation. When he opened them again, the wounded man was there. The words were like venom on his lips.

‘You were supposed to keep me good, but no no no no! You thought you could get me back to her with your little scheming.’

He was still ranting when he wobbled his way to you and knelt at your feet. You loathed the prospect of his help to make it to your bed. You did not wish him to wipe your tears as if you were the child he still thought you were, in need of his protecting hand from a cruel world.

It was Mama Charity’s fault, for reporting your innocent conversations with the boy from three doors down as something dangerous and unbecoming of a ‘cultured’ man’s daughter like yourself. You had seen the way she looked at your father. She was not his type, you knew that, but it did not stop the woman from trying.

For the first time, it occured to you that your father would never forgive the meddling of your childhood years. It had made you a tainted thing in his eyes. Incapable of bringing goodness out of him. With every misstep, he would take you back to it. You realised then that to survive, one of you must cease to exist, just like in his stories of street triumph.

He helped you to your feet and guided you to your room with care. With every step, tears fell hot on your cheeks but you bit your tongue. In his eyes, you were still his little girl. Not ready for the world and all its vices. He watched you like a man ready to lunge to your rescue as you lowered yourself onto the bed. For a moment, you were like two frightened children staring at one another, each grasping for security in the other.

‘Tomorrow you can do better,’ he whispered loud enough for you to hear and the spell was broken.

When your eyes closed with the heaviness of sleep and pain, you prayed that if you woke again, you would have been chosen to survive.

Something fluttered in your belly. It felt like the end of something.

***

Eight days have gone by since Maziko walked out the door. In that time, you have turned your words upside down and taken shears to their wings. You have cried for innocence lost, eyes glued to the living room door, waiting for him to retrace his steps into your home and back into your life. You have watched the sun rise and dip into the horizon, felt its warmth on your skin, your heart impenetrable.

As day number nine dawns, you are wide awake from a fitful sleep. You taste the heaviness in your mouth and the mingling smell of sweat and urine staining your sheets. Today you promise yourself a new beginning. Freedom from a past you have guarded closely and paid for dearly with your life.

You busy your hands, wash and clean until the surfaces shine, and adorn your body with oils for your journey home where everything began. Where you were once a little girl stolen from her mother. Where you returned once upon a time, hoping for relief, but found closed fists and hearts that could no longer take you in. With every step, you feel the weight get lighter. Having now lost what you feared most, you know nothing else will grind you down.

***

‘He fell sick and died,’ you had told your mother when you arrived at her door after days of travel, weeks after your father’s death. She held you in her embrace, and for a moment, you were happy you had come home. Until her body stiffened, as though transported back in time. Could you be any different from the man who had stolen you all those years ago? You knew right then you could never say what you had done.

***

When you stood in your mother’s compound on the day of your return at seventeen years old, you did not know that years later you would walk over the threshold of your mother’s home one more time as a cleansed thing. Ready to unburden yourself for the last time.

The sirens of the police car will not have to announce their arrival. They will come for you a little after 2pm. You will hold your arms out without a fight, your mother convulsing with her tears. She will enfold you in her embrace, kissing your cheeks the way she had when it was just you and her. ‘My baby has come home’ she will say, and for a moment, you will think, This is love.

~~~

- Yanjanani L Banda is a writer from Malawi. She was the 2023 fellow of the Literary Laddership for Emerging African Authors, was shortlisted for the 2023 Kendeka Prize for Literature and the 2022 Bristol Short Story Prize. Her work has appeared in Brittle Paper, Afritondo Magazine, Spillwords and the Quilled Ink Review.

~~~

Publisher information

An undocumented immigrant returns home after facing the indignities of the American dream working as a washer of the dead—only to be met with a tragedy. A child struggles to come to terms with the fate of their beloved one-eyed chicken Otuanya, who is treated as a family pet but is destined for the cooking pot. A family lives in fear of the dreaded Shadow Fever that haunts their town, keeping them trapped indoors after sunset lest they risk falling into an eternal sleep.

From realistic explorations of family life, parenthood and infidelity, to gritty noir and fantastical horror, the stories collected here are a testament to the endless imagination and possibilities of African literature. These witty, provocative and compulsively readable stories grapple with feminism, patriarchy, class and exploitation and showcase these writers as astute observers of life. This anthology is a generous feast of diverse, delectable narratives that offers something for everyone.

Midnight in the Morgue also features three remarkable South African literary talents: Sibongile Fisher, Morabo Morojele and Nadia Davids. Davids has the distinction of being the first South African to win the Caine Prize since Lidudumalingani in 2016. Her story, ‘Bridling’, about a conflicted early-career actress performing in a subversive theatrical production was hailed as ‘a triumph of language, storytelling and risk-taking‘ by Chika Unigwe, chair of judges.