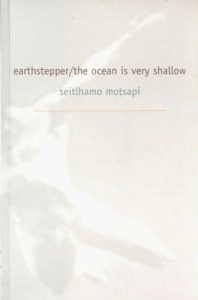

Sihle Ntuli talks to Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi about subverting language, the beauty of Black creativity, and his seminal poetry collection, earthstepper / the ocean is very shallow, thirty years on from its publication.

~~~

& though the ocean clamours in a roar

though the waters invoke the drowsy spirit

of thunder

the ocean is very shallow

a time short like loss

a mountain low like hate

the ocean is very shallow

—Extract from ‘the sun used to be white’

Sihle Ntuli for The JRB: The first time I came across your work was in 2009, during my time as an undergraduate at Rhodes University in Makhanda. Your debut collection became a pillar of my own creative pursuits, in large part because of how it spoke to me as a young man driven by the rhythms outside and within the crevices and curvatures of black spoken language. I am grateful for how your work willed me on to begin searching for my voice, a voice that can resonate with our people, that seeks to gather the spirit of the dead, imagined worlds and all the places that I have lived. This year earthstepper / the ocean is very shallow celebrates thirty years since its first publication in 1995, and my first question for you is about that first process of gathering: how did you gather and do you feel your intentions with this work have been realised?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: earthstepper was the culmination of a very long process that started in the early nineteen-eighties. I was fascinated by words and their endless possibilities. Reading the poetry of writers like Kamau Brathwaite, Wopko Jensma, ee cummings, Sonia Sanchez, Jayne Cortez, Amiri Baraka, Haki R Madhubuti, and many others, as well as religious texts, and listening to musical icons like Marley, Marvin Gaye, Coltrane, all helped define the voice that is earthstepper.

Some of my earliest reasons for writing poetry were to show off how well I had absorbed Bantu education and how good I thought I was with English. So my earliest poems, and some of the poems in the book, were really ostentatious bluster, although no one has been brave and honest enough to tell me so. Judging from the analysis and criticism, many evidently intelligent and well-meaning people seemed to divine hidden and subliminal meanings and messages from the book that I never knew existed. But equally, many simple folk, who breathe the same polluted and hopeless air as me, warmed to some of the poems. What the book thus achieved, through some of the poems, was to magnify my vain streak, but others showed that words can often assume a life of their own beyond the machinations and ego of the writer.

The JRB: My grandfather’s house is situated on one of the busy main roads in my neighbourhood, so I grew up with a constant soundtrack of movement. People walking about, taxis hooting, but my most vivid memory is of the engines of the Durban Corporation buses struggling up a steep hill, and the sneezing sound their doors make when opening. I decided that I would gather this and make ‘KwaMashu F-Section Bus Stop’ the opening poem of my collection Stranger. Your poem ‘sol/o’ does this beautiful thing of drawing the reader in with an honest account of journeys past, present and future. How did you come to decide on ‘sol/o’ as the poem to set the tone for your collection?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: The words of Christopher Okigbo will live in me forever: ‘I am the sole witness to my homecoming.’ Also the line from Kofi Awoonor: ‘I have no sons to fire the gun when I die.’ I fail to see the rationale for voluntary solitude, whether for so-called spiritual reasons or any other. On the other hand, the African proverb that others complete you is as derivative and deluded as they come. The truth lies somewhere in between. I have never respected so-called adventurers who chase records to be the first to cross some helpless desert or a tired ocean and yet cannot spend an hour living with others, especially those who are different. Instead of climbing Everest, try living in Makoko, Kibera, Khayelitsha or even Harlem for a day. So the idea is to recognise the common good, but always to acknowledge that your path is your own.

The JRB: One particularly memorable aspect of earthstepper is its unapologetic modification of the English language. The dislocating and discombobulating effects of my own movement between township, suburb and back again have had a lasting effect on me and almost always bleed into my work. This is the basis of the multilingual aspect of my own poetry. So my next question to you is about the origins of your language use. A poem like ‘tenda’ is one of many with conventional English language use, and then in the very next poem, ‘soro’, we get the refrain ‘i erred, i erred’, and there is the immediate sense you are prepared to challenge the language rather than adhere to it. As we go deeper into the book, your variations produce a wonderfully radiant, rhythmic and varied use of language in poems like ‘brother saul’, ‘drum intervention’, ‘djeni’ and ‘malombo paten dansi’. What inspired this stylistic approach in earthstepper?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: For many Black South Africans, our first exposure to English is at school, but the problem with the formal curriculum is that it is designed to ensure we speak proper, stuffy English. Even today, we still measure a person’s intellectual development by their proficiency in English. People who struggle with English are largely humiliated, despised and regarded as cognitively impaired or insufficient. When I was doing my honours I was once publicly berated by a Black lecturer for speaking to him in Sesotho in the corridor, even though I was one of the top students in the class. I discovered the poetry of people like Kamau Brathwaite, ee cummings and Wopko Jensma, and it opened up new possibilities for me. I also loved patois, creole and so on, for their hybridised and subverted appropriation of English, and it all drew me into exploring what other possible and potent versions of the language existed, but which we were warned not to use for fear of being ridiculed. When one freely but confidently expresses themselves, the results can be liberating. It can be like whipping your dead dog back to life.

The JRB: While doing research for this conversation I came across a biography of yours that was used at Durban’s Poetry Africa festival in 2002. The sentiment I found was one of deep disillusionment with poetry. Not long after, it was said that you had ‘retired’ in 2002, following your departure as a speechwriter for the presidency. In my correspondence with The JRB editor Jennifer Malec, she expressed the view that talented debut authors tend to disappear for a number of reasons, not least economic. Could you comment in your own words on how your perceived retirement really occurred, and the true reality of your situation?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: I never retired from poetry. There was a time when I felt I had said everything I wanted to say, poetry-wise. Spiritually, I also felt that I wanted to recede from a life of superficial self-significance and be non-existent and silent, as ninety-nine per cent of us are. Artists, analysts and academics seem to think they have all the answers to the world’s complex contradictions and that the progression and success of all life somehow depends on their precocity and special powers to which the majority have been denied access. I wanted to be like everyone else, but whether I succeeded or not I will leave to thinking folks.

The JRB: Your use of creole and patois in earthstepper features alongside references to Bob Marley, with hints of ska and reggaeton, so the first part of my next question is concerned with your attentiveness to sound and rhythm in your poetry. As a brief aside, what were you listening to around the time you were writing earthstepper? More specifically, how did you factor orality and rhythm into the composition of your work, and who were the authors who may have influenced this direction?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: My musical tastes are diverse and have not changed since earthstepper. It would require a volume to list all the artists who have shown me, especially, the beauty of Black creativity. They include Coltrane, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, obviously Marley, and the early reggae magicians like U-Roy, Marvin Gaye, Malombo, Orchestra Makassy and Orchestra Baobab. Music plays a huge role in my life and it has seeped into my writing as well. The musicality of Kamau Brathwaite and Wopko Jensma also left an impression.

The JRB: One question that I find myself working through is my ever-changing stance on spirituality. In my youth, and even now, the collision of Zulu and Christian doctrines often took place in my family’s living room, and when there was no room for compromise, the results could often be brutal. In earthstepper, there are references to the Bible alongside, speculatively speaking, what some might consider to be Rastafarian elements. In your own words, could you speak on how earthstepper delves into spirituality and where you stand now?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: I have always wanted to explore the existence of a benevolent creator and this led me early on to study, to varying degrees, all the major traditional religions, as well as Rastafarianism and African spirituality. It was thus inevitable that some of this spirituality would eventually find its way into my poetry. I have a deep respect for people who consistently believe in God, such as my wife and my mother, and for many simple people who have never made it their business to ask too many questions about the contradictions we experience on a daily basis. But personal tribulations over the past twenty or so years have substantially eroded my belief in a compassionate creator.

The JRB: My final question is one about futures. The challenge of pursuing more poems or more bodies of work beyond the first is in itself a compelling conundrum. I’ve found the difficulty is not so much in reinventing the wheel, but in finding different ways of perceiving it. I’ve come across some of your newer poems in recent issues of New Coin and the Evergreen Review, so for this final question I would like to ask you about where your line of thinking is now, as a poet in 2025. Do you still feel compelled and motivated to pursue poetry, despite the many and often difficult challenges of our genre?

Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi: Over the last three years I have written a few poems and rewritten some of the stuff in earthstepper. The newer poems have none of the self-conscious gesturing and linguistic contortions of some of the earlier work. I believe great poetry should not be a statement or a gimmick. My newer poetry is embarrassingly bare and unassuming, and so it will not appeal to some of the people who were enchanted by the ostentatious posturing of some of the earlier work. I realised a long time ago that not everyone appreciates expressive or creative honesty. As in politics, those who make the loudest and most dramatic statements are often the ones who grab attention. But I am no longer interested in the applause and meaningless appreciation of intelligent people who often read non-existent meanings and messages into my poetry. It is what it is, like me—detestable, unfashionable, but ultimately honest and frank and not asking for much in return.

~~~

- Seitlhamo Thabo Motsapi is married to Monosi and has four children. He Lives in Bela Bela. He has written poetry since the early nineteen-eighties, culminating in earthstepper / the ocean is very shallow (Deep South, 1995/2003).

- Sihle Ntuli is a poet, classicist and editor from Durban. He received his MA in Classical Civilizations from Rhodes University, and briefly lectured in Classics at the University of the Free State and the University of Johannesburg. His writing has been supported by the Johannesburg Institute of Advanced Studies in South Africa and the Centre for Stories in Australia, through the JIAS Fellowship & Patricia Kailis Fellowship respectively. He also served as the editor-in-chief of South Africa’s oldest literary magazine, New Contrast, in 2023. He is the 2024/2025 Diann Blakely National Poetry Competition Winner, a 2024 Best of the Net poetry winner and a Pushcart Prize nominee. His poems have appeared in Wasafiri, Transition Magazine, Poetry Ireland Review, Poetry London, and elsewhere. He is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Rumblin’ (uHlanga, 2020) and The Nation (River Glass Books, 2023), and two full length collections, Stranger (Aerial Publishing, 2015) and Zabalaza Republic (Botsotso Publishing, 2023).