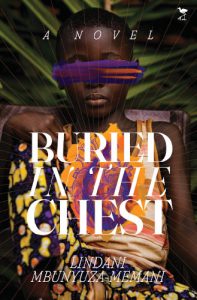

The JRB presents an excerpt from Buried in the Chest by Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani, winner of the 2024 Dinaane Debut Fiction Award.

Buried in the Chest

Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani

Jacana Media, 2025

Read the excerpt:

Before they were grandmothers, they were young. They were girls. They had names—Gogo was not Gogo, but Cynthia. As Cynthia she was free with a heart that loved so loudly her face shone a bright smile. Although she was shy until the age of fifteen, she’d landed on her feet by age sixteen, the age she had her first period. It was as if the blood had given her the strength to love and be decisive, at times almost cruel. She’d loved Busoso, who later became Mr Buso. She’d been sure he knew it because of his constant visits and the gifts he brought her. But their meetings were marked by silence, at best halting conversation.

Head tilted to one side and a smile reaching to his ears, Busoso would look at Cynthia while pretending to have been sent by his father to see about Cynthia’s mother’s milk cow. Cynthia’s mother was blind, and the villagers were kind to her and her daughter.

‘Our milk is rich,’ Cynthia snapped at him.

‘You’ve not tasted—’ Busoso would try to respond, but Cynthia would cut him off and he would nod, smiling again.

Neither said the words they wanted to say. But both knew. Both agreed. Words were unnecessary.

It was after she had become bold that Cynthia met Sipho. This cooled her encounters with Busoso. Sipho turned out not to be Sipho, but a young man with another name from another village far, far away. Cynthia still called him Sipho for that was the boy she’d fallen in love with. She called him Sipho even after the political party of Ntabeni, the Eyensci, told her that he wasn’t from their Eyensci region. Cynthia later learnt that her Sipho was in hiding. The Eyensci was moving Sipho from village to village until he reached some border where he could skip the country and fight for the freedom of black people. He disappeared when Cynthia’s belly began to bulge. The villagers gossipped. Cynthia had no doubt.

Mavis was born—brown and silky. She arrived around seven in the morning when Cynthia was supposed to be taking the cow to the veld. Mavis would never know a father. On a day when the wind was strong, Cynthia whispered into Mavis’s fontanelle never leave. Love. You must love. Be strong. You are going to have to be strong. Into the feisty wind she said pack away these words and remember them always. Cynthia had been sure that her words would slip into the plump folds of Mavis’s skin where they’d remain hidden and ready to be used when Mavis needed them.

Cynthia had balanced Mavis on her right hip past the time it was healthy to carry a child. She never wanted to put Mavis down, never wanted to be separated from her. When Mavis was learning to walk and fell like all toddlers do, Cynthia’s voice turned from scolding to a softness accompanied by tears that rolled down her face. She didn’t want her Mavis, a fatherless child, to feel different, notice the difference, talk about the difference. Cynthia hoped that her Mavis would never know pain, never have to know the sting of heartache and of separation.

Cynthia carried Mavis on her hip even when she opened the kraal for her mother’s cow and the four goats, feeling the chubbiness of her thighs against her. In the summer months, they’d both sweat, and Mavis would slip down Cynthia’s body, but Cynthia would grab her before she fell. She protected Mavis, hated the idea of her suffering any hurt. The abiding pain of not having a father was suffering enough. Cynthia was relieved that when her mother died, Mavis was too young to feel the pain of loss.

In her grief, Cynthia poured all her love into Mavis. The other mothers accused Cynthia of being too soft on Mavis, of never letting the girl grow up. Cynthia didn’t let Mavis fetch water from the river alone. She also never let Mavis do the weekly laundry on her own. And she never spanked her, which was the way children were punished. Cynthia preferred to show the child where she had gone wrong. One Friday, Mavis came home from playing cakemud and practising wedding songs so she and her friends could dance for pennies at weddings that December. They arrived home at the same time. Cynthia was returning from her job in town doing laundry and cleaning up after two white families each day. It wasn’t something she liked to do but after her mother died she was forced to find work. She needed the money so she could raise Mavis well, provide her with food and shoes and a coat for when it was windy, and buy her dresses with yellow flowers on them.

That Friday, when Cynthia had planned to sleep off the week’s sore muscles so she could clean and mend whatever needed mending in their rondavel the next day, Mavis began an old conversation Cynthia had previously shut down.

‘Is my father Mr Buso?’

‘Watch it child.’

‘Why is he here all the time? People say he is my father.’

‘Is he here now?’

‘No. Why won’t you tell me?’

‘No, who? Awunamsila ngoku?’

‘No mama—’

‘Didn’t I tell you that I am your mother and father?’

‘I know how babies are made—’

Cynthia’s exhaustion turned to anger that bubbled up and could not be contained. She jumped to her feet, grabbed Mavis, and spanked her hard on the back and the buttocks. Mavis squealed and tried to loosen herself from her mother’s grip. It was no use, her mother’s eyes were orange like a glowing flame. Cynthia spanked her Mavis until her arm went limp. Then she napped right there next to her daughter who was mumbling her cries.

When she woke up, Mavis was massaging Cynthia’s arm. They cried together. Cynthia realized that beating her daughter had been unnecessary. Still, Mavis had spoken back, refused to be silent, and needed to be taught to know when talking back was unacceptable. But she had not needed to hit her. As Mavis massaged her mother’s arm and, as they cried, Cynthia promised to always use words, gentle words when correcting her.

There were only kind words in the years to come. Mavis was among the good students in school. But then something befell them like a rope tying together the hind legs of a cow getting ready to be milked. Cynthia noticed that her daughter was no longer shaped like the number ‘8’. She was a small letter ‘b’. Again, the other mothers said it was because Cynthia had not been strict enough with her daughter, had not hit her when she’d gone astray. In reality, Cynthia had not noticed since she was gone most of the day washing and cleaning for white families in town. Sometimes it was dark by the time Cynthia arrived home.

When she asked Mavis about the pregnancy she didn’t respond other than crying, apologizing and promising to do better. She said she would find work in the city and send money for the baby. Cynthia was disappointed and hurt and angry. A part of her wanted to hit Mavis, show her the severity of what she’d done. Pregnant at age twenty with little education. It made her even angrier that she herself had also been pregnant in her early twenties with no education. The village people always added and no husband.

Cynthia paced around the rondavel, thinking of hitting her daughter. But what if Mavis retaliated, pointed out her double standard, called her a hypocrite? Mavis was following in Cynthia’s footsteps and Cynthia knew this would lead to a hard life. She had wanted a different, a better, life for her daughter.

She didn’t hit her. She spoke quietly to Mavis, telling her of her disappointment and offering her support. She didn’t reveal all the pain she felt. She swallowed most of it. It stayed inside her heart and clogged her lungs. She never let it spill out of her. The pain travelled to her shoulders and legs and stayed there.

Pregnant girls were a spectacle in Moya. They were ridiculed and insulted. Cynthia’s kind words and love were insufficient to shield Mavis from the villagers’ ridicule. All the hurtful words Cynthia didn’t say were said to Mavis by the villagers. Mavis didn’t escape shaming, couldn’t. From her pregnancy until the child was born families scolded her as if they were competing to hurt her the most. It had become custom that after giving birth the girls left the village to find work, leaving their babies in the care of the scolders, the shamers.

Fathers stayed. There were never shamed. They were boys. Boys were always experimenting. Girls were always being experimented on. Sometimes girls wanted the experience so they could talk about it, be informed, and inform. Sometimes they had no choice but to participate. To the village it didn’t matter how the baby came to be. Shame flowed in only one direction—towards the mother. Moya like Ntabeni was left with grandparents, fathers and children.

Cynthia evolved from being Cynthia to being Mama to being Gogo, Unathi’s Gogo. It was six months after the wind had carried Mavis away that Gogo began to snap at every mention of Mavis. She didn’t want to hear her name mentioned. By the time Unathi was eight years old and asking about her mother, Gogo had buried Mavis deep in her chest.

‘I don’t know,’ Gogo said truthfully every time Unathi asked about her mother, Mavis.

‘When is she coming back?’ Like the child she was, Unathi persisted.

‘I don’t know. I don’t want to—’

‘Maybe she will come back one day. Maybe I will find her.’

The conversation would end with Unathi looking hopefully at Gogo.

~~~

- Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani has an MFA in Creative Writing from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. In May 2017, she received a doctoral degree in Mass Communication and Media Arts from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Her terminal degrees were, in April 2011, preceded by an MA in Media Studies from Nelson Mandela University. While creative non-fiction is her real love, Mbunyuza-Memani also dabbles in fiction writing. She hopes to write poetry one day, but not soon. When she is not writing or observing one or another social or cultural phenomenon that she knows will end up in one of her stories, she is teaching, because that is what English professors do—they teach and help to shape young and all minds.

~~~

Publisher information

‘Buried in the Chest deals with familiar themes in South African writing, but with an approach that is astonishingly fresh and accomplished. The author interrogates the painful history of apartheid with a unique literary approach, and the book will linger in the heart and mind long after reading. This poetic novel is the kind of inventive truth telling South Africa urgently needs as we continue to grapple with the past and imagine a better future for all.’—2024 Dinaane Debut Fiction Award adjudication panel

Buried in the Chest is a poignant tale of self-discovery, love, and community set against the backdrop of post-apartheid South Africa.

The story follows Unathi’s journey as she searches for her mother, Mavis, while navigating her identity. Raised by her grandmother, Gogo, in the village of Moya, where mothers are eerily absent, Unathi must confront the complexities of her sexuality, cultural heritage, and sense of belonging.

As she explores lesbian love, interracial relationships, and the quest for her mother’s truth, Unathi must also contend with the harsh realities of identity politics and the masks she must wear to survive.