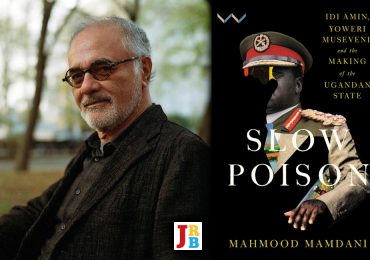

The JRB presents an excerpt from Sanya Osha’s latest book An Ethos of Transdisciplinarity: Conversations with Toyin Falola.

An Ethos of Transdisciplinarity: Conversations with Toyin Falola

Sanya Osha

Anthem Press, 2025

Read the excerpt:

Sanya Osha: There is a powerful Pan-Africanist element in your work. Can you discuss the intellectual antecedents to this development and the kind of vision that influenced it?

Toyin Falola: Every movement in the world begins as a response to a particular experience. Movements are developed from the awareness of people about certain regular experiences that they understand would have a negative effect on them on the occasion that no effort is made to challenge the system. We, therefore, can talk about Communism as an idea and then as a movement, the same way we can talk about the intellectual movement of the Renaissance era, among others. This means that these engagements have come to evolve into a more formidable action group that people make conscious efforts to improve on or, in some cases, preserve. In a sense, this definition makes an implicit conclusion that movements are an integral part of human civilization. As its crucial component, it underscores the process, time, or stage that people get to before they change their story, as the formulation of movement has been globally known as the generator of powerful forces that usually change the course of actions and direction of a people. For Africans, there seems to be a justified reason to create some form of movement for themselves in the unfolding world. One, the experience of political conquest in the hands of European imperialists is generally and totaling in its consequences. This leaves not many African countries off the hook of remote domination.

In addition to this, Africans became victims of cultural genocide in recent history, from about 500 years ago to the present. They experienced, in stark reality, the dehumanizing consequence of humanitarian atrocities committed against them from centuries of revisionist history, defeatist syndrome arising from it, identity politics, mudslinging of their moral and ideological values, condemnation of their historical beliefs, and the perpetual incineration of their intellectual, economic, and social institution to the extent that they were browbeaten into accepting what does not represent them as theirs. This happened to such an extent that the African child is already bequeathed with a dented and broken image that would be working assiduously to undermine him even before his birth. The ones who have been born were unfortunately raised in an environment where the content of their education was drawn from a European perspective handed down specifically with the intention to re-engineer their mindset toward Africa: their identity. Thus, the African child already makes a sworn enemy of their root even before hearing or knowing anything about it. He assumes erroneously that what is called Africa must be oozing out barbarism in great magnitude and must be representative of backward civilization in the amazing perimeter. It must be symbolic of shambolic people with infantile intellectual capacity.

One would notice that the atmosphere is already rigged against the African child, and for him to become proud of his continent and, by implication, his identity, there must be some profound events that would not only change his perspective but also rekindle his spirit, instill in him the genuine feeling of African identity where he would be proud to associate himself with that identity. The Pan-African movement of today focuses on embarking on activities that would rekindle the African spirit on a global scale, to strengthen the bonds of these people of African origin so that they would understand who they are and be proud to associate their engagement with it. This bond will have no respect for geography as it would encourage an outreach of people regardless of their physical location to accommodate themselves as one without sentiment for the part of the continent where they come from. Apparently, such a movement understands for a fact that the history of continent-wide slavery has mandated a need for an indivisible association for all the descendants of theirs who suffered tremendously from this barbaric practice that almost obliviated their origin out of the human world. Whereas this movement has been predated by similar forceful ones, such as the Negritude movement, it has a different tenor.

Pan-Africanism understands that while slavery of the past centuries was a political necessity for the imperialists to accomplish greater economic growth, the events of the capitalist culture of the current world do not indicate that slavery would change anytime soon. Of course, the physical bondage of humans through chains might have had a legal stoppage. Slavery is perpetrated in different ways that cannot be fought, especially when the combined forces are weak. Although other groups of people have experienced the brutal hands of slavery, however, Africans continue to remain victims of their very strange behavior of lacking coordination. Creating a movement of such orientation was a political necessity to enhance their survival. Without making efforts for the advancement of agitation, they would continue to fall victim to the capitalist West that plots their downfall using whatever means available. Although the movement emphasizes the need for the consolidation of African greatness through their return visit to their African origin, it is not rigid in its persuasion. The pioneers are aware that movement and migration are a constant human experience that would continue when and where comfortable. In essence, what was important was not to advocate for complete return; it was to understand what home was about in the first place.

To this extent, the advocacy for returning home is encouraged at the philosophical level. Africans are expected to understand the critical importance of accepting themselves. Meanwhile, accepting themselves begins by identifying with the philosophical constructs of African origin. This definitely would assist them in understanding what their role in the world is and how they can navigate their existence to a rewarding and satisfactory level. We cannot contest the fact that the suppression of Afrocentric ideologies has contributed, essentially, to the displacement of African identity in the world of the moment, as Africans themselves are not only denied access to their identity, they are programmed to detest it in all manner possible. To abandon one’s historical identity this way is to single oneself for undeserved subjugation and subduing experiences in the hands of the people who are perpetually seeking their downfall. In essence, Africans are bound by a similar fate which calls for communal actions and collective loyalty in pursuing them. To that extent, Pan-Africanism promises to present them the golden opportunity to fight their fights and be saved as a people or perish as an identity.

To be honest, the movement has birthed quite a number of political institutions that embrace the responsibility to attune Africa as a collective identity with the global community. The Organization of African Unity that metamorphosed into the African Union is an indication and evidence of progress. In all intent and purpose, this body seeks to compel a set of political actions and principles that will, for the most part, handle African affairs for the benefit of all. Through it, intra-African trade will increase and cross-border movements will be facilitated, both of which would bring improvement to the continent as a whole. Whereas this group might not be as formidable as others in terms of the power and influence they wield in determining their safety, they are, nonetheless, making impressive leaps that showcase them as being progressive. The Pan-African movement is greater than this, but the fact that they are making great strides is an indication that they are on the right path.

Today, it is not uncommon to find Africans of different cultural origins combining their engagement together and functioning in unison. This, among other things, is evidence that Pan-Africanism is making the right decisions and choices to advance the African worldview. If the sociocultural movement achieved the above-stated goals within the time of engagement, one cannot imagine what adding academic force to it would bring in the long run. I have a role to play, one, as an individual who experienced, firsthand, the negative consequences of removing an individual from his or her cultural and ideological roots, and two, as an African who desires freedom from all its definitions and conception—to be of notable addition to the movement. Even if one refuses to have anything to do with Pan-Africanism, as a scholar, one would be placed in an intellectual quandary in the process for so many reasons. As scholars, especially the ones raised in Africa, one does not have access to the cultural resources from which one would draw for one’s intellectual productions. In this case, one is helpless in a sense. For one, you do not have the liberty to weave academic information of other people’s origin against which you lack substantial knowledge. And even if you have the access, you need to take a position; it is either you favor the predators in the jungle of scholarship whose writings continually hunt the prey, or you stand firmly by the side of the prey whose access to freedom and self-expression is being usurped by the predator. It is my conviction that staying on the side of Africa would achieve numerous purposes for me.

I envision an African space where people would be free in the real sense of the word, and to achieve that, it does not materialize by mere wishful thinking. One needs to understand the politics of writing and make efforts to direct things in ways that would benefit one’s origin and identity. Africans are free only to the extent of breathing. Take breathing away from the equation and you will notice that Africans are not actually free. People who continually run to the other world to seek economic survival, not fulfillment, cannot be said to be free. One cannot adjudge free people who have zero tolerance for their neighbors under the fear they can be persecuted anytime because the said neighbors are nursing the same thoughts. I mentioned ‘economic survival’ and not ‘fulfillment’ to delineate what the people who come to Africa do and what Africans go to other places to do. When you move out of your comfort zone so that you survive and have access to daily meals when you work, you do not seek fulfillment; you seek survival. That exactly is what happens to many Africans in other places. Meanwhile, they have untapped resources that can be converted into results for everyone to benefit. By the combination of leadership ignorance, and greed, the African leaders pay poor attention to the myriad of natural resources, tapping only the ones that can fill their pockets and not satisfy their people. It is the resulting hardship from this senseless engagement that undermines the progress of Africa. Pan-Africanism in this modern day addresses these issues.

Sanya Osha: You are not only a scholar but also a public intellectual who is very concerned about bridging the traditional divide between town and ivory tower. One of your latest initiatives in this regard is the popular TF Interviews. Can you discuss the various motives for this kind of action and thinking?

Toyin Falola: It occurred to me at a point that the capacity of intellectuals and their potential to transform human society are unlimited. In every sound mind is an arsenal of ideas with unlimited possibilities to change the status quo of their environment for good. Whereas one can only measure these people through their actions when they evaluate that the situations of events are unsuitable for future development. They are those with foresight and the prescient clairvoyance to see what the future would be when a particular set of actions and activities are taken. Unlike others, they understand the importance of decisions and the inevitability of their consequences. In essence, when they understand that a society is moving toward a particular direction, they would immediately evaluate what it would potentially bring to the people and society in the future. If they perceive potential danger, they are always making sacrifices to ensure that the world takes appropriate measures that are considered less risky or less dangerous for humanity. Their lives are used as necessary sacrifices to better the conditions of the world. We would see this in the life of Socrates, a philosopher who, despite his generation’s limitations to understand the consequential events of their excessive intermix of religion and politics, continued on his path of truth-telling as his contribution to his generation. He persisted, even when he was resisted. Though what happened to Socrates is evidence of many things, the interpretation is subject to individual sentiment or bias.

For anyone who is a religious apologist, decapitating the philosopher’s life through poisoning would have been considered a necessary action to prevent anti-religious individuals from influencing the minds of the innocent majority. However, for someone not tied to religious morals, what Socrates did was deserving of encomium, if not for any other reason, but for the single fact that he offered a fresh perspective from which people could see humanity and the world generally. Apparently, people in the past would have thought about making such changes, but the understanding that the sacrifices it takes to do that would be too much of a luxury that they can afford prevented them from such indulgence. The focus of my argument about this philosophy is not on his efforts against religion and religious politics; it is on the idea that sacrifices are needed to transform an otherwise vulnerable society that has been captured and subjugated by those profiting from misgovernance, misdirection, and mismanagement, which is the case with many African countries. Quite a number of people are benefiting from the present arrangements, and it takes a different level of confidence to challenge it. If you ask me about bridging the gap between the town and the gown, the question you are asking is inherently affirmative of the understanding that there is actually a gap between the two. If we already have such a reality, the right question would be, ‘Why is there a separation between the town and the gown, especially when one understands that they have a common goal, and that is the fact of bringing changes to human society?’ To answer this latest question, I need to bring you into what happened in my mind recently. I was beginning to look at the African world and immediately saw various divisions. These divisions are not based on philosophical expediency; they are constructed alongside the same area where the colonizers introduced us as Africans. This is why some of us take every business of decolonization very seriously. But I would not particularly highlight what I saw in these African divided spaces—that is better suited in any of my future books. But as a hint, I would refer to what happens in the Western world, with which I am equally familiar. Look at the Western world where they import all the forms of instruments we use in Africa (political, ideological, economic, and even spiritual). You have the category of people whom you call the upper class, the middle class, and the lower class. The first category of people under the idea of democracy put in place measures that would render the powerless others vulnerable. The subjugated ones would only be needed when it is time for elections, and they always tilt toward the ones who offer them succor when they are hungry.

Now, more people are ‘hungry’ (in its ideological sense), and when they follow a particular angle of decision, we would generally say it is the choice of the majority. The question is, how then is the majority sound in making these decisions? You would see this is a very complex situation. Mind you, these Western people use the same language to communicate their ideas, exchange economic interactions, conduct their political affairs, and handle their education. Now, imagine what would be the case for us Africans who adopt their ideas but use different languages in our social interactions. Do you not, therefore, see that this division would be more complex and, for that reason, foretell a fearful future for the African people? What I am saying, in essence, is that Africans have imposed the gap between the classes of society. In fact, you would notice too that the credit for that saying goes to Western civilization. In pre-colonial Africa, there was no town and there was no gown. In other words, the town was the same with the gown, and this helped in enabling inclusivity in political, economic, social, and cultural engagements. But in one way or the other, we have (un)consciously imported the idea of town and gown and the separation it brought to the African space, causing unwholesome damage to our civilization as a people.

You would have noticed by now that what drives my passion in doing the TF Interviews series is to first return the African values to their appropriate place. This begins with the recalibration of society into its non-divisive entity that would usher in a new perspective to everything we do. Those who we have unconscientiously removed from the issues that concern their existence would first have a sense of belonging. As researchers, we understand how profound an experiment would be when given all the necessary attention and concentration. This experiment, I must be frank with you, has proved to be a successful one. Beyond what could have been envisaged, we are now getting to know the ‘insignificant’ majority and understand how they view the ‘decision-making minority.’ In the past, they have loathed and disagreed with the direction the elites have decided to take their society, and they have begun to react. The irony is that, as elites, we have failed to connect their actions to protest and resistance, but I will show you a few. The pre-colonial father did not abandon many of his responsibilities for whatever reason, and the pre-colonial mother did not have to nurse fears of exclusion because there were institutions that responded to their cries and answered them. Anything related to moral principles is handled by every member with the awareness that their actions have a greater consequence on society. Today, people don’t just care about these things.

Although what I have done is a surface-scratching effort aimed at restoring the values that are inadvertently eroding the African sociopolitical and sociocultural pace in the name of creating a gap where none existed. If you asked me if the separation is necessary to keep the sanity of the academic community intact, I would tell you that such an approach is merely evasive. It is avoiding the greater looming danger, some of which we are seeing gradually in contemporary times. There are ways to indicate if society is measurable along the lines of people’s access to education or not. When it is done haphazardly as the current schools of African scholars are doing, there will come a time when the danger would be completely invertible. The primary concern is to interrogate the crucibles of the intellectual property locked in the minds of the ones we call gowns. They are invited into our space to understand and begin to reshape their views about life by juxtaposing things on their own. Although the platform you have alluded to has been in existence for some time now, it has achieved a commendable result in its relative recency. One of the things we have achieved with it is bringing together a community of scholars who are mainly of African progeny and are located in different countries of the world. These scholars have gained an understanding of what different societies are and how their organization contributes to the conditions they find themselves in, not only through the reading of texts but also through firsthand experience. As African scholars in the diaspora, we have been able to spread the influence of Pan-African identity to bring intelligent minds together so that we can benefit from their critical ideas that would bring value to everyone. What is sacrosanct here is that the physical bridge erected by the nature of human geography has collapsed for very obvious reasons. There existed a form of difference among scholars of different academic disciplines and career landscapes, making it impossible for them to join forces for common advantage.

With the power of technology, we have harvested the fermented intellectual properties of many African scholars who come to our space and discuss several things. We have invited scholars who are passionate about Afrocentric legitimacy and de-escalation of colonial structures that have re-engineered the cognitive system of the African people. At the appropriate time, they educated us on why the various areas of Africa’s political, social and economic life have continued to experience their shadow selves. Through them, we have learned that the combinatorial contributions of colonization, neocolonialism, and excessive assimilation of Western ideas have sterilized the African systems and made them vulnerable to external manipulations, aggressions, and threats. These educated fellows bond together and, like us, are also beginning to see how the importance of maximizing opportunities presented by technology and the media is almost inexhaustible. Rather than divert their energies to wrong activities or engagements of zero cultural and political advantages, they have continued to see why it is commonsensical to come together under the same umbrella to rejuvenate dying African spirits and restore their dignity. Gradually but steadily, we are creating a social hub where everyone considered intellectually fertile, irrespective of their town or gown status, would be brought to our space for an interview. We would be able to learn from them and identify with their perspectives as much as they demonstrate a good knowledge of their topic. We do not deserve a continent divided for reasons we don’t know. Most of the challenges we face as a people become enduring because we do not articulate them in most cases. We would not even know that many of our problems can be immediately resolved when we talk about them to one another. If we continue to underplay the importance of communication, we will keep the suppressive structures erected by the European imperialists and give them the power to divide us. If we are scholars, we should understand the benefit of making use of every opportunity that presents itself to us. If past Africans organized continent-wide actions and agitations that won them independence and international recognition at a time when there was no internet or social media, this current generation has no excuse not to do exceedingly better. We need to take advantage of the virtual space that offers us the opportunity to interface across borders, interact across countries, and interchange ideas across nations. We are making impressive landmarks in that trajectory already.

~~~

- Sanya Osha, scholar, writer and author of several books, lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

~~~

Publisher information

Toyin Falola is one of modern Africa’s most prolific public intellectuals. This project seeks to illuminate the mind of this modern master in an age of transnationalisation.

‘Osha’s insightful exploration of Toyin Falola’s intellectual contributions brilliantly illustrates the importance of convivial scholarship and its profound impact on African studies. This book is essential for anyone interested in collaborative, inclusive knowledge production and the future of knowledge creation.’―Francis B Nyamnjoh, Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Cape Town

‘Sanya Osha’s detailed, three-dimensional analysis of Toyin Falola’s epistemic preoccupation with the idea of Africa is a welcome addition to the body of knowledge. This robust life-writing engagement shows us the importance of recognising the centrality of agency and selflessness in the process of advancing the African worldview.’―Babátúndé Fágbàyíbó́, Professor of International Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Falola’s astounding intellectual production must be one of the mysteries in the intellectual world. It has transcended the confined world of historical research into broader horizons that include the role of the public intellectual.

The present study would undertake a rigorous analysis of the origins, continuities and discontinuities of this transformation. This means we have to recast the debates regarding who is a public intellectual from a multiplicity of discursive situations and historical and cultural contexts. We have to employ methodological parallels from North Atlantic intellectual traditions. How did the role of the public intellectual emerge in the first place in world intellectual history? Addressing this question would enrich this research endeavour immensely.

In interrogating comparative discursive formations, we shall re-evaluate the roles, functions and achievements of continental intellectuals such as Betrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre, Andre Malraux, Albert Camus, Michel Foucault, Edward Said, Wole Soyinka and Pierre Bourdieu. Again, this discursive element will give this study a global appeal and range.