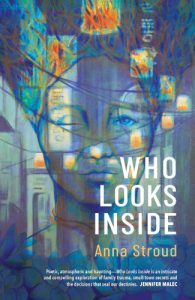

The JRB presents an excerpt from Who Looks Inside, the debut novel by Anna Stroud.

Who Looks Inside

Anna Stroud

Karavan Press, 2024

~~~

ONE | 제일장

The phone rings.

My eyes burn against the sound. I try to hold on to my dreams, but my ears surrender first.

My arm escapes the pillow, and my fingers fumble around the side table. I flick a switch and light floods my stubborn lids.

Barefoot, I plod to the cupboard against the opposite wall. I dig out my phone from where the sound is vexing my socks.

‘Yes?’ I croak once I’ve hit the green button.

‘Your mother,’ says a voice on the other side. ‘She’s dead.’

A click and then nothing, besides the ringing in my ears.

Shock mingles with sleep in my cotton-wool mouth, constricting my throat. I sink to the floor. I lean my head against the cupboard door and stare longingly at the grey duvet.

So, this is how it ends.

I don’t know how I fall back asleep, but I do. I dream of mathematics, being half an hour late for an exam and forgetting to study for half a year. I can’t find my timetable, my student card is gone, the Afrikaans lecturer says my time is up …

When I awake, my neck accuses me of abuse. I stand up from the floor and make a cup of black coffee. I swallow it, make another cup and let it go cold. I sit down at my desk wedged in between the cupboard and the bathroom door.

I start to write.

I don’t go home for the funeral.

TWO | 제이장

Except, perhaps I do go home for the funeral, and that’s when I see her.

THREE | 제삼장

It’s six o’clock in the morning. Outside the kitchen window, rows of red-brick buildings glimmer with soot and bird shit in the rising sun. A woman coughs three times and spits as she pulls her hotteok cart through the sprawling streets below. I close my eyes and savour the memory of almond flour and chopped nuts drizzled in melted butter and brown sugar. Across the road in a temple above a kindergarten, a monk calls the morning prayer. I make a peanut-butter sandwich, take a bite and change my mind. I take two more bites before it strangles me. I put the sandwich in the recycling bin, lock the window and start packing the essentials: underwear, jerseys, jeans, three shirts and a few socks, all black. A black coat in case April in South Africa is colder than I remember. I grab my wallet, my passport and a copy of Fahrenheit 451. At the last minute, I add Norwegian Wood to my suitcase. The rest of my books berate me for leaving them, and I promise to be home soon.

Back at my desk, I write a note for my neighbour, asking him to feed the stray that lives with me. I won’t be gone longer than a week, it reads. Death in the family. I stick the note to his door and, for a brief second, I hold my ear against the plywood. I imagine I can hear her in there, my treacherous kitten, no doubt purring on his lap as if he’s fed her cream. Perhaps he has. I’ll have to speak to him about that. When I get back.

The bus stop is a short taxi ride away, the airport a six-hour journey by bus. It’s been a long time since I braved the twenty-odd hours and thousands of kilometres separating me from home. I buy my ticket and settle into the shiny red seats of the intercity bus. I start to open the window, but then I notice my fellow passengers throwing me disapproving looks. I close it again and drink from my water bottle instead, trying to ignore the rising panic in my bladder at the idea of such a long trip.

I should have packed more books. I should have sent word that I was coming home. I should have done a lot of things, but there’s nothing I can do about them now.

An ajumma sits down next to me. ‘Hodo kwaja?’ she offers as she holds out a small walnut cake to me.

I accept with a ‘kamsa hamnida’, and bite into the soft pastry with the sweet red bean filling.

She laughs and bites into one, too. ‘Mashiketa?’ she asks, and I nod. ‘Ye, mashisayo.’ It really is delicious, and she stuffs more cakes into my hand, before stretching out her legs and making herself comfortable. Her shoulder touches mine, and I steel myself for the journey ahead, my mind already at the end.

FOUR | 제사장

When I was small, Pa took us to Port Elizabeth by train to visit his brother. Our compartment had leather seats that you could fold out into four beds—one for Pa, one for Ma, one for me, and one spare. By day, we sat and watched the scenery change. I was surprised that not everywhere was hot and arid. I wondered where the thorn trees and ostriches had gone. It was 1994. The next year, my father wrote a letter to Nelson Mandela asking for money. Mandela never replied, reaffirming my father’s belief that the Afrikaners’ days were numbered.

A few years after my first voyage, I went to Mossel Bay on a school trip where I saw the ocean for the first time. We took a motor boat out to see the seals—twenty preteens, stuffed in life jackets, squashed against each other—and I started menstruating. I didn’t stop for six months. I stuffed toilet paper in my underwear and prayed no one would notice.

When I was seventeen, I skipped out on a mathematics summer school when I hitched a ride to Cape Town, where I spent four glorious weeks smoking Rothmans Red, kissing boys and learning to drink cane and Cream Soda.

Twenty-two hours, two international flights, my first ride on the newly built Gautrain and another local flight later, I’m nearly home. The realisation shakes away the cobwebs as I navigate the white Ford across the treacherous roads of the Outeniqua Pass. I have to stay focused. I will walk in, greet the family, start making the funeral arrangements.

But perhaps someone else has taken over the arrangements, maybe one of my mother’s sisters. I wonder which one of them called me in the middle of the night with such an abrupt message. I wonder how they found my number.

It’s late afternoon when I pass the giant white sign welcoming me to the Garden Route. I drive to my mother’s house as in a dream, down the dirt road framed with thorn trees, pecking ostriches and identical municipal houses. A rock hits the underside of my car. Shit. They’re going to deduct money from my credit card to pay for that.

Then I see it. The small yellow house at the end of the dirt road hiding behind a thick fence of spekboom. Asters waiting to bloom frame the steps to the front door, and a bare apricot tree leans crookedly to the side. Wizened succulents dot the yard, and to the left, a gnarled grapevine bides its time. In the centre of the garden, a young apple tree shoots for the sky.

I stare at the empty driveway. Did my father own a car, or was that another dream I had? There’s smoke coming from the chimney. For the first time, my body registers the chill.

I wonder how my aunts got here without a car, while regretting not renting something hardier for these roads. No doubt this week home is going to cost me a fortune. I can see it now: all my relatives lining up for a ride and a handout. I swallow and get out of the car onto the dirt road.

The gate squeaks, and I flinch. You silly girl, how could you forget about your squeaky gate? I walk up the concrete path to the front door and raise my hand to knock but then, I hesitate. I look up at the chimney again. Who would be cooking now? Surely not my aunts, I don’t remember them ever lifting a finger on the odd occasion that they came to visit my mother. I follow the trail of smoke around the house to the back, and I stop when I reach the kitchen window. On tiptoes, I peek through the lace curtains. My mother insisted on two sets of curtains, a lace one and a solid one, a petticoat under her dress, double stitches when she darned my socks.

There’s movement in the corner of the kitchen, and from the darkness a figure emerges. She’s humming as she carries a large enamel dish from the pantry to the table. She pats a handful of flour on to the bare wood of the kitchen table, her face hidden behind a puff of white smoke swirling in the late afternoon sun. She empties the contents of the dish on to the floured surface and slowly begins to knead the dough as my mother used to do, pulling a section from the one side, stretching it out, and folding it back to the centre. Then repeating the motion on the other side, knuckling the dough into submission. Over and over, until her hands are caked in white. But as the flour settles, I realise that those are not my mother’s hands. Hers gleamed with cracks whether she cared or scolded, as if she had washed them with rocks and moisturised with butter.

No, this woman in my mother’s kitchen is not my mother. For one, she looks to be in her mid-thirties. Her black hair—dyed, judging by the jagged roots—is pulled back into a ponytail; her eyebrows must have been pencilled on in a hurry this morning. She’s a little chubby, but that doesn’t stop her from wearing a red miniskirt over burgundy tights and a pink jersey that’s too tight and low-cut for her age. She has the same round nose as my mother. The same grey eyes, and the same frown splitting her forehead into two uneven slices. But she couldn’t be my mother, unless she’s looking well for seventy. And for being dead.

‘Who are you?’ I jump at the voice coming from my hips. A child stares up at me. ‘Are you friends with my mommy?’

What to say? I clear my throat for an extra second to get my story straight, while taking a good look at the boy. His whole face frowns up at me. He scratches the sandy brown hair overgrowing his white collar, and a green caterpillar creeps in and out from his nose, winking at me.

‘I’m here for the funeral,’ I say at last.

‘Oh,’ his face relaxes. ‘Did you know my granny?’

‘Your granny?’

‘Yes, she died.’ He looks down at his shoes. ‘The funeral is on Wednesday.’

‘Who is your granny?’

The frown is back, but he says her name, my mother’s name, identifying her as ‘granny’. It can’t be. I wasn’t gone that long, I don’t have children and besides, I’m an only child. This boy must have it wrong.

‘And your mommy?’ I smile to show him we’re just talking, but my heart is tripping over furniture inside my chest. ‘What’s your mommy’s name?’

What he says next leaves me cold. Droplets prickle my scalp.

He says my name. The one before the revision.

I swallow, my head spins, but I persist in the interrogation.

‘Can you repeat that, please?’

But he’s not looking at me anymore. His head is tilted towards the kitchen and the aroma of butter melting in the Dover. It reaches out an invisible hand that grabs him by the collar and pulls him towards the door.

‘My mommy’s name is Hanna,’ he rushes over the words. ‘Her mommy was Ouma Hannie.’

‘I see.’ I don’t see.

He takes a step towards the door, but then he remembers his manners and twists back towards me. ‘Are you coming?’

‘Not today, thank you.’ I try to think of an excuse, but he cuts me loose.

‘Okay, bye-bye then.’ He’s by the door, his hand on the doorknob, when he turns around one last time and says, ‘You look like my mommy, but you’re not as pretty as her. Are you her cousin?’

‘No,’ I say as I start walking away. ‘I’m not her cousin, just an old acquaintance of the family.’

He frowns at the new word, then shrugs and starts turning the doorknob. I leap into action. I’m around the corner and by the front gate in seconds. I open it and squeeze through just before it can squeak again. I’m in my car, hoping the boy hasn’t told his mother about the woman peeking through the kitchen window yet. I start the car, but before I drive away, I take one last look at the house—my house. There’s the rusted gate with the big homemade sign warning intruders to Pasop vir die hond. Beware of the dog. Lumkela inja. There are all the plants and trees, testament to my mother’s green fingers, growing long and dark in the shadow of the setting sun. Something—a tree rustling or a door opening—makes me jump and I speed away, sending dirt and stones flying.

In my rear-view mirror, behind the yellow house, the sun spreads strawberry jam across the horizon.

~~~

- Anna Stroud loves books. Like, really loves them. Authors, too. She once travelled over two hundred kilometres by bus from Daegu to Wonju in South Korea to hear Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o speak. She’s been reading Antjie Krog since the age of eleven, even the sweary bits. She moved close to Love Books so she’d never miss a book launch. Naturally, she’d become a writer, with stories appearing in Grocott’s Mail, Cue, WordStock, The Sunday Times, Books LIVE, City Press, The Reading List, Daily Maverick, The Johannesburg Review of Books, tagged! and Business Day, among others. When she’s not writing, she’s walking her husband, Sean, and two dogs, Raven and Poe, at the park. Who Looks Inside is her debut novel.

~~~

Publisher information

I wish I could stay where I am right now.

In the in-between, neither here nor there.

The past behind me, the future a distant dream.

The news of her mother’s death pulls Hannah back from South Korea to her childhood home in the Karoo where she discovers that she has never escaped her abusive father and passive mother. That, in fact, she has been there all along, baking bread and raising a son whose father might be a local farmer she is having an affair with.

Her world unravels as she struggles to separate the life she has built for herself from the one she survived.

Unsettling, eerie and evocative, Who Looks Inside explores themes of childhood trauma in a working-class Afrikaans family.

‘Poetic, atmospheric and haunting—Who Looks Inside is an intricate and compelling exploration of family trauma, small-town secrets and the decisions that seal our destinies.’—Jennifer Malec