Butter is keenly attuned to the many ways the private sphere runs on the disproportionate work of women while deliberately rendering that work unnoticeable, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

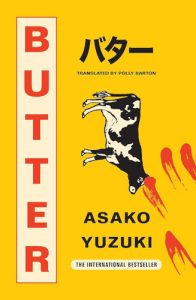

Butter

Asako Yuzuki (translated by Polly Barton)

Fourth Estate, 2024

The front room of Asako Yuzuki’s engrossing food noir Butter is an interesting one. The novel tells the story of a young tabloid journalist, Rika, who makes contact with a notorious murderer who is alleged to be responsible for the deaths of a string of lonely older men. The two women are from different worlds, but the narrative draws them both into a shared realm of transgressive pleasure, anchored in the experience of what it feels like to eat hedonistically.

If the narrative premise suggests that Butter is another entrant to the teeming realm of novels-about-food (a club whose members are actually novels-about-food-as-vehicle-for-something-profound), then that is no bad thing. The idea that food enjoyed without overt restraint is sensuously emancipatory expands easily into sociopolitical commentary when read against the lives of women. In this respect, Yuzuki’s novel invites interesting comparisons with an array of books, such as Lessons in Chemistry, say, or Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen. Butter, however, is somewhat darker, opening out from an easy thriller into a more complex portrait of social damage in an appealing and intriguing way.

Yuzuki is diligent in providing the necessary details. We learn early on that ‘food and fashion—the things that women were supposed to have a particular fondness for—had always left Rika indifferent’. Our protagonist is an ascetic young woman who is quietly proud of her disciplined appetites: she keeps trim, has a boyfriend she sees infrequently, and generally keeps her mind focused on her work:

Rika was the sole female journalist who was also a permanent-contract employee. Of the four other women who had joined the company at the same time as her, two had requested to be transferred to other departments, and two had left for health reasons. The women who had joined the company before her and shown her around had married and moved to other departments: books or sales. The job was impossible to manage alongside pregnancy and childcare, unless you had magical powers.

Rika’s only indulgence is a puzzling crime case. Manako Kajii, the object of her growing obsession, sits in Tokyo Detention House, convicted of murdering three men over the course of six months. Kajii’s story is a news sensation: using a dating service to target single men looking for companionship, she maintained a life of luxury funded by a string of hapless suitors. Now imprisoned and awaiting a retrial, she is a source of national fascination for reasons that seem to illuminate the novel’s central preoccupation:

What the public found most alarming, even more than Kajii’s lack of beauty, was the fact that she was not thin. Women appeared to find this aspect of the case profoundly disturbing, while in men it elicited an extraordinary display of hatred and vitriol. From early childhood, everyone had had it drummed into them that if a woman wasn’t slim, she wasn’t worth bothering with. The decision not to lose weight and remain plus-sized was one that demanded considerable resolve.

In many societies, fatness is framed in abject terms, as a congealing of the undisciplined or inattentive self: the push-pull spectacle of decadent desire that Kajii evokes for Rika struck me—with my fat person’s defensiveness—as both absurd and hyperbolically typical of a world in which fatness is redolent of a loss of control. Kajii’s cultivation of an excessive, rebellious femininity, embodied in the fullness of her figure, is always threatening to overload the novel: her presence is at once too one-note and too bombastic to sustain credulity. Regardless, she captivates Rika, who sets out to try and land an exclusive interview with her.

The journalist is drawn under her mercurial interviewee’s spell, and the two women develop a charged intimacy that intensifies as Kajii sends Rika on a series of appetite-expanding food journeys. I do not recall reading many novels that linger so pornographically over the matter of eating as Butter does. Very few of us have a truly healthy relationship with food. Mostly, we use it as a substitute for something else. In Butter, every dish Rika makes at the urging of her unlikely mentor is laden with the bodied desire to eat on one’s own terms:

This was all it took, she thought, to experience a sense of satisfaction of a kind she’d not had before. To make something yourself that you wanted to eat and eat it the way you wanted—was that the very essence of gratification? Until not long ago, she’d had no idea what it was that she wanted to eat, but since she’d begun using her kitchen, she was becoming able to picture, albeit vaguely, the objects of her desires.

Without ever slipping entirely out of its genre, the novel gradually unravels a very different kind of story. It becomes clear that Kajii’s fatness is a conscious and deliberate dig at the ways in which women are required to make themselves disappear behind the roles that cis-het women are normatively obliged to take on: as caregivers, as consorts, as sources of comfort for men who blithely accept these things as their entitlement. Butter is, in fact, keenly attuned to the many ways—marriage inequality, the trivialisation of domestic labour—the private sphere runs on the disproportionate work of women while deliberately rendering that work unnoticeable. The book lays bare what is askew in how women—Japanese women in this instance—have been compelled to submit themselves to a social role that is profoundly disempowering. As the novel lopes on towards its conclusion (there is a twist in the tale), Rika grows increasingly detached from the crushingly banal normalcy that had once seemed like a theoretical possibility for her life. Her development as a character would put you in mind of a bildungsroman, if she weren’t in her thirties.

Yuzuki’s writing—ably translated by Polly Barton—is free of snags, preferring an easy, fluid sentence and even pace to more difficult arrangements. Over the course of four hundred and fifty pages, this means that the story can feel a little languid: at times, the novel’s emotional ambience can feel a little too low-key. But if nothing jump-scares at a critical moment, then the novel is still rapier sharp in the way it records observations about the way people—men especially—behave in the domestic sphere:

At the weekend, my husband would experiment with smoking bacon on blocks of bricks in the garden, or caramelising kilos of onions at a time, or making curry from scratch. The sort of cooking that men do when it’s a hobby for them, in other words. And it’s fun, all that, because it’s an experiment, a special activity that you do when you have the time, and that you don’t mind spending money on.

Who does not know some variation of this man? What the novel addresses, with unfailing accuracy, is the ongoing and systemically enabled badness of men, and how tiresome it is to be tasked (thanklessly) with looking after them.

Butter is a book that many people will buy purely as an aesthetic object. A cover that looks like Kill Bill: A Novel will see this book scoring highly with the Instagrati. There is something terribly covetable about a Japanese literary phenomenon being made available for our touristic gaze, isn’t there? But it is a really fine read, exploring some difficult ideas with a bold fluency that marks it as more than a flash paperback.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on X.