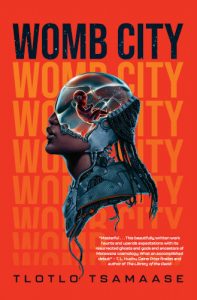

The JRB presents an excerpt from Womb City by Tlotlo Tsamaase.

Womb City

Tlotlo Tsamaase

Jacana Media (Mother imprint), 2024

08:00 /// THE BLACK WOMB

This is my third lifespan.

Since there’s no record of an eviction for criminal reasons, the original owner of this body must have willingly evacuated these skin and bones at the age of eighteen for reasons I’m not privy to, but her parents continue to love me as if I’m their original daughter. The second host was evicted for a heinous crime. As per my country’s criminal legal regulations, my body is fitted with a microchip that observes my behavioral patterns to deter criminal recidivism. It is an operating system, implanted in my brain stem to remotely control my body during criminal activities.

Privacy violations are rife on such bodies until their assessment confirms their purity, which can take anywhere from a couple of years to decades. My purity test is close, but we’re neither given an exact date nor told what to expect, much like the forensic evaluation. Passing the purity test means I could ultimately be free of the microchip. I’m terrified that one tiny wrong move could destroy my chances. I need to be perfect. I need to be perfect. I must be perfect.

One day, I’ll be free.

But how can I be free when my womb is a grave, killing any new life that tries to form, any seeds that my husband plants in it?

A black cloud hangs over me. We lost the fetus during our first round of IVF, and now we trundle about the house, broken and forlorn, having thrown all our savings at it. I didn’t pay the alarming cost for mind transfer reincarnation to receive an infertile body with an artificial arm, even if it is a surgically attached, fully functional bionic prosthetic. I couldn’t tell it apart from the rest of my body until my doctor peeled back the synthetic skin to show me, the first day I was revived. But I don’t know why this arm was amputated; my parents won’t tell me what happened to their first daughter in this body, so I don’t know if it’s the first or second daughter who lost this arm, or how. I feel robbed. I filed a report against the Body Hope Facility (‘The Body Hope Facility. Body hop, body hope; we give every soul hope.’), but it’s in their indemnity clause, which allows them to supply bodies they deem in perfect condition, not what the host considers perfect; there’s nothing I can do.

It’s back to the old routine now, the ovulation alert waking us to morning darkness. Elifasi thought it’d be exciting to do it in the shower, the one thing we can vary, the only thing we can control in our lives. Suddenly he wasn’t in the mood, so I said, ‘Just stick it in and cum. It’s not like you ever last anyway.’ His mouth puckered. He hammered me. I leaned against the cold tiles, zoning out into an out-of-body experience. I was a robot; the sex was mechanical.

I’ll need to work something out so he forgives me for my quippy remark.

I was pregnant before, for five months. Second trimester. We were glowing, more in love than ever. As a parent, all you think about is how you’ll protect this newborn once it’s outside the safety of your body. That’s all we fussed about, purchasing nanny cams, baby monitors, an AI tool that would monitor his little breaths. A surgically installed GPS app tagged into his nervous system, just in case we lost him. I’d read terrifying stories of newly minted parents losing a baby, forgetting them at the mall. Such a horrid thing for a parent to do. That would never happen to us.

But we lost our little boy. Within the boundaries of my body. Inside me, not away from me, not forgotten in some random place, but right beneath my skin, below my heart.

You just never, ever think that your baby could die inside you and you wouldn’t be able to tell. To be pregnant for five months—then to come home three nights after an emergency induced labor with an empty, scraped-out womb, holding that blanketed, precious stillborn— is devastating.

01:34, when the dead fetus was removed. Intrauterine fetal death, they called it. I gave birth to a dead child.

I have given birth to three dead children.

What was worse was that fed-up, ‘I don’t know what’s going on but something smells funny’ look of betrayal my husband shot at me. ‘Really? You couldn’t tell you were carrying a dead baby? Our baby. That you’ve been throwing money at the fertility center to have. Didn’t you find it strange he wasn’t kicking? For three fucking days. Jesus Christ, you killed my son.’

The memory of it sends panic blazing through my body. I didn’t drink, I didn’t smoke, I didn’t overwork. I ate healthy, I exercised mildly, I came home early. I did everything right. I paid my taxes, as if that should have a bearing on my fertility. My husband later apologized, but you can’t erase what’s said, what’s done. Words leave a certain damage, just as much as a bullet in the flesh.

I’d stared at the fresh white lilies drone-delivered to our home, tagged with a note: From the Koshal family. We’re terribly sorry for your loss. Our family’s hearts are with you. Anything you need, please don’t hesitate to call. Only, I know he sent it, not his wife, like she’d give a damn about my pregnancy loss. He must have done it behind her back—she’d never allow him to send another woman flowers. I know he meant it, too. I glare at my husband, and sometimes I wish he was another man named Janith Koshal.

I shuffle into work, sleepwalking out of the elevator. Jan’s message is the first to come through. Morning, had a dream about you last night. Link up? I ignore it. I need to stay away from him. But we run in the same business circles, so we’re bound to bump into each other. I married someone I need to stay loyal to. Jan’s married, too, with twins, and that’s what I envy, what he has, which makes me appreciate the natural way he flirts with me … It turns me on, turns me—the robot who’s been malfunctioning for years—on. I hate to think this but

what if,

what if,

what if

Jan can impregnate me?

I know the doctors at the fertility center said I’m infertile, but that ‘what if’ is making me think terrible things. Maybe, just maybe … it’s not me who is malfunctioning, but Elifasi.

I lazily press my finger against the biometrics scanner. I yawn as the door buzzes me into the open-office plan of the glitzy Gaborone School of Architecture (GSA). I gulp down coffee that’s not pumping any effective caffeine in my system. Most of my colleagues are hyped, but some are agitated about the board meeting regarding student marks, absences, failures …

My back stiffens when an early-bird student trudges in, one hand pressed against her arched, aching back. I’m teaching several courses as an architectural design lecturer. On the days I’m on campus, I see pregnant freshmen traipsing through hallways, courtyards, into our offices begging for marks and submitting late coursework. I want to scrape out the fire of pure anger that devours me with my nails and teeth. Because I hate it. I hate how easy it is for a child to have a child. They’re too young to take care of themselves, let alone a baby. It’s amazing how it happens: you just fuck and you’re pregnant. The ease and simplicity is so foreign to me. As if my body is made to just have sex without leading to procreation, like I’m being punished for being successful in other areas of my life. In gossip rags that often demonize me for owning a criminal body, they started calling me the ‘Black Womb.’

~~~

- Tlotlo Tsamaase is a Motswana author. Her novella The Silence of the Wilting Skin is a 2021 Lambda Literary Award finalist and was shortlisted for a 2021 Nommo Award. Tsamaase has received support from the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, and her story ‘Behind Our Irises’ is the joint winner of the Nommo Award for Best Short Story (2021). Tsamaase’s short fiction has appeared in Africa Risen, The Best of World SF Volume 1, Clarkesworld, Terraform, Africanfuturism Anthology, and is forthcoming in Chiral Mad 5 and other publications. She is a 2017 Rhysling Award nominee and a 2011 Bessie Head Short Story Award winner. She obtained a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Botswana and won an award for design architecture. Tsamaase is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Chapman University.

~~~

Publisher information

This genre-bending Africanfuturist horror novel blends The Handmaid’s Tale with Get Out in an adrenaline-packed, cyberpunk, body-hopping ghost story exploring motherhood, memory and a woman’s right to her own body.

Nelah seems to have it all: fame, wealth and a long-awaited daughter. But, trapped in a loveless marriage to a policeman who uses a microchip to monitor her every move, Nelah’s perfect life is precarious. When a tryst ends in an accidental death, Nelah’s life spirals out of control as she goes to desperate lengths to hide the killing and save the life of her yet-to-be-born daughter who is growing in one of the government Wombcubators, daring to hope that she can keep one last secret.

Set in a future Botswana, a cruel futuristic surveillance state where bodies are a government-issued resource, this harrowing story is a twisty, nail-biting commentary on power, and bodily autonomy. In this devastatingly timely debut novel, acclaimed novelist Tlotlo Tsamaase asks, just how far must a woman go to bring the whole system crashing down?