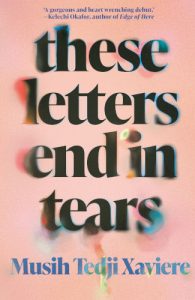

As a novel centred on lesbian love set in an intensely homophobic country, These Letters End in Tears by Musih Tedji Xaviere is frustratingly pessimistic, but it is also abundantly joyful, writes Shayera Dark.

These Letters End in Tears

Musih Tedji Xaviere

Jacaranda Books, 2024

Set in Cameroon, Musih Tedji Xaviere’s debut novel These Letters End in Tears unfolds partly through a series of undelivered letters written by Bessem to her lover, Fatima, who has been missing for thirteen years since their arrest, which the former blames on her naivety at the time.

While Fatima had erred on the side of caution—having already experienced hostility at the hands of her supposedly pious elder brother, who was determined to make her a good Muslim and uphold their family’s honour—Bessem had resented the masks they were forced to wear as lesbians, though her femininity, unlike Fatima’s overtly masculine disposition, offered her some protection from the abuse and violence meted out to the LGBT community.

‘I was tired of hiding,’ she explains, in one of her hundreds of letters. ‘I was furious at the world for turning us into cockroaches, only comfortable in dark places. I wanted to hold your hand in public, to show you off to my friends.’

That decision would prove disastrous, when Fatima’s brother decides to teach her a public lesson. He and his friends descend on Fatima and Bessem’s favourite bar, beat them up and haul them off to jail, where they are physically assaulted by police officers because of their sexuality. ‘That was the night we were forced to grow up. Me mostly,’ Bessem writes of the ordeal.

Thirteen years later, Bessem, now a university lecturer, still masks her true identity in the face of pervasive homophobia. In Bamenda—‘a part of Cameroon where nothing and no one ever gets out’—the police are known to raid LGBT-friendly bars and have arrested students suspected of lesbianism at her school. And with the advent of the internet, anti-gay vigilantism has a wider reach, allowing citizens to blackmail unsuspecting homosexual people online. Bessem is compelled to mute her opinions among colleagues who support corrective rape and longer prison sentences for ‘the gays’.

On the rare occasion when she does speak up, citing the ongoing civil war between Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon as a far more important issue than the persecution of same-sex lovers, another lecturer responds: ‘Lesbianism is worse than war.’

As absurd as this comment sounds, it nonetheless gives a chilling sense of the climate of fear, claustrophobia and silence that communities marginalised because of their sexuality have to navigate in order to survive. As Bessem reflects:

There’s a mild kind of fear you carry with you when you don’t quite fit into a place, an awareness that the little comfort and good standing you have in your life is only there because people don’t know the real you. And once they do, everything could be taken away.

Bessem and Fatima’s story is not solely one of tragedy. In their brief time together, they manage to snatch some moments of happiness, from making love, to enjoying quiet moments on a secluded hilltop, to getting married in a private ceremony witnessed by Fatima’s best friend, to socialising with like-minded people in the friendly local bar.

But given the powerful influence of religion and family ties, both women find themselves swimming against the tide of their upbringing, which demands marriage to the opposite sex and conformity to the precepts of Islam, or, in Bessem’s case, Christianity. It’s no surprise, then, that neither Bessem nor Fatima’s parents are keen to discuss their sexuality, leaving it to hang over their heads like an unspoken rebuke.

Upon her release from prison, Bessem endures an uncomfortable borderline abusive deliverance session with a pastor, turns down suitors arranged by her mother, and, in a state of despair, considers converting to the faith of her missing lover, much to the consternation of her gay, ex-Muslim friend, who questions her intentions.

Stuck in a ‘place between misery and sweet recollection’, Bessem eventually finds a new lover, but does not give up her search for her old flame. Her quest leads her to stalk Fatima’s brother, now an imam, in the hope of solving the mystery of her decade-long disappearance. While trailing him, she discovers that his religious piety is no more than a sham—the same hypocritical pose that seems to spare no one in Cameroonian society, including the religious, closeted gays and lesbians who bay for the blood of their fellow queer citizens.

In addition to its exploration of religiosity, These Letters End in Tears is animated by gender expression and the expectations that come with it. By loving Fatima as she is, Bessem quickly learns that masculinity and femininity are not tied to any one gender, so much so that when her new lover holds the door open for her, she chastises her for imitating typical male behaviour because of her masculine orientation:

‘Look, all human beings have masculine and feminine sides. Some men lean more toward their feminine side, others toward their masculine side, and the rest are somewhere in the middle. It’s the same thing for women,’ I say. ‘You are a woman who is more in tune with her masculine side. I don’t think that means you have to copy men’s cultivated behaviours and I don’t think it’s something you should be proud of, to be described as behaving like a man when in truth you’re only being yourself—a woman, a different type of masculine, free to form your own unique behaviour.’

Although there are occasional flashes of literary flourish in the novel—Fatima’s eyes are ‘a shade of brown like upturned soil with a ring of starry gold around the pupils’, their German-built school is made up of ‘multiple hulking structures sitting on a broad green bed in the purlieus of Bamenda’—the writing in These Letters End in Tears is straightforward and restrained on the whole, perhaps reflecting the narrator’s phraseology and speech rather than the author’s style. In any case, the rendering, intentional or not, lends another layer of verisimilitude to the letters and to Bessem, who is, after all, an economics lecturer.

These Letters End in Tears is a welcome addition to the growing list of literature centring queer lives in African societies eager to deny their existence with claims that they are un-African or misguided vessels of Western immorality. It may be frustratingly pessimistic, but it is also abundantly joyful.

- Shayera Dark is a writer whose work has appeared in publications that include LitHub, Harper’s Magazine, Al Jazeera, AFREADA, The Kalahari Review and CNN.