The JRB presents ‘Blue Boy Lagoon’ by Keith Oliver Lewis, the winning short story from this year’s Short.Sharp.Stories Awards.

The highly commended stories this year were Jarred Thompson’s ‘What We Ride In On’ and Shanice Ndlovu’s ‘Of Somo Seeds’.

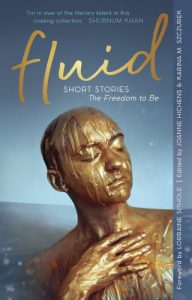

The stories will be published in the forthcoming anthology Fluid: The Freedom to Be, which will be launched at The Book Lounge in Cape Town on Wednesday, 10 May 2023, at 6 p.m. Launch details here.

Fluid: The Freedom to Be

Edited by Joanne Hichens and Karina M Szczurek

Tattoo Press, 2023

Blue Boy Lagoon

By Keith Oliver Lewis

Tjarlie and I ricochet off the school fence. It was his idea to go for a swim at the Boulevard.

‘Naai getuie, it’s moer hot,’ he said, crumpling a turquoise tie in his front pocket.

Every summer’s day in Paarl East feels like solstice. Your blood turns into sunflower oil. The sun bakes your skin like koeksisters. In class, it is even worse. You are a coconut drowning in your own resin. Tjarlie’s Grasshoppers, which I call The Leaning Towers of Pisa, leap through secret passageways and liquorice tunnels hidden in Paarl’s breast. If he could see my thoughts, he would recognise the same: clandestine isles with staircases that lead to nothing. We are far from our territory, so we have to camouflage, almost be invisible.

Smoke drags out of Tjarlie’s mouth. ‘My broe, I don’t smaak to run for my life in this poese heat.’

A charcoal Vitruvian drawing floats to the ground. I follow it at hugging distance, two centimetres away from death’s regular spot. After dogging hovering cranes, gulls and hawkers, we could finally enjoy the pus-blue sky. AWOL clouds leave a wounded heaven feeling abandoned.

‘Kiddo,’ he calls my eyes from the scar, ‘keep a soute outside the shop.’

‘Nomme,’ I hear myself becoming a clone of Tjarlie. ‘Nomme’ has many meanings, but in this context, it means ‘let it be so’. A lemonade-pink bow wrapped around the tail of a shooting star. An act. A proverb of kept promises. I spot printed-out portraits of thieves at the till. Somehow, the men in the pictures are used to being wanted and the women look as if they are missing.

Mr Miyagi is watching five screens on one Quasimodo TV. I see Tjarlie in black and white snaking through the crowded draws. Tjarlie looks like Chaplin. We are always under surveillance. Everyone watches us, especially the blue Mercedeces with their machetes, Die Son looking to broker another mass murder for six rand, and, worse, the self. He is spying on us from inside a fleshy pink solitary confinement. Geppetto pulling strings and not allowing us to be just boys.

The name of the shop sprouts pimples on my hull. Every community in this town has a Broadway store on some corner. Flashbacks bore holes and memory creeps in like a flood. I am probably seven years old again, conscious and cautious about not carrying the shopping bags just as Mammie carries her handbag. It is easier to hold it that way, swinging from your elbow, but Deddie does not like that.

‘Punch him,’ Deddie shouted with Offender’s arms in his dagha hands.

I cannot really call that my first fight, because he was the referee and my tag team partner. His mouth was a rowdy audience whose disappointment in me weighed more than the rivalry with the opponent. In this corner, we have every brown boy. Those known and unknown. Laaities with my father’s features. Villains squinting with the same questioning eyes attached to my grinding hips. Ninjas with his murderous mouth and giggling index finger pointed at my falsetto. And in this corner, we have me. Rocky slowly sinking in a lagoon carved by bags, or was it a ring? Whatever it was, I did not want to partake. Deddie scarfed his arm around Enemy’s neck. His ulna choked him by the Adam’s apple while Deddie’s free hand gripped the noose. The bystanders shouted: ‘Chokehold!’ Victim’s Adidas slippers levitated.

‘If you don’t moer him, I’m going to donne YOU,’ Deddie warned me. My body traded skin for soapstone and my knuckles struggled to construct a wrecking ball. ‘Slaan sy wint uit! Show him you’re not a bunny.’

Grief and condolences ballooned my chest. Boys like me learn from an early age how to distinguish between the two. One is death; the other is dancing with death. My shuttering heart laid claim to the grief. I am always in mourning, but I still do not know who the empathy is for. Maybe for him, my peer, hanging from Deddie’s arms. He who attempted to murder me with just one pejorative adjective. It could have been also meant for my father. I have seen the cracks and the honeycomb he uses to plaster them. He hides his sorrow in his fist.

‘Those jeppies are vaak, my broe.’ I hear Tjarlie mumbling in the background of my recollection. ‘Are you vanging trokke, my broe?’

I am still stuck in my head. Tjarlie once said my dif is as massive as a library. It is an athenaeum of labyrinthine isles filled with spider webs and neurons. My mind is supposed to be a safe space where I can rest on Japanese tissue, perfectly puzzled in cracked spines, but most times it is spiralling barbed wire. I love to read. Tjarlie always tells me that I will one day go insane from reading so much. I, however, do not like to read in this archive. I just look at the pictures. Drawings of me riding horse on Deddie’s back and Mammie standing hands up for Chuck Norris with gun fingers. He probably wonders where I store all our negatives. The bad memories of Deddie never leave the dark room.

‘Dê!’ Tjarlie cranes a bag of yellow peaches in my hand. His daffodil fingers exhume something from his pelvis. He is a magician. Tjarlie’s eyes, diluted, misdirect mine. ‘Abracadabra!’ A two-litre granadilla Twizza crawls head first from a slit in his crotch. ‘Poof!’

My armour disappears. ‘Tjarlie, you boef!’ I crash my hand into his. ‘Are you happy to see me, or is that just a cooldrink in your pants?’ Our blood palms lock while the silhouettes of our thumbs chain. That handshake, like many other things, is a secret.

By the time palm trees start following us, whipping their dreads back and forth in the wind, our lips are citrus-coloured. We find ourselves alive at the Boulevard also known as Bergrivier, or Canoe Tar if your skin is ivory. This serpent splits Paarl asymmetrically into Europe and Africa. It was as if God ordained Apartheid. I once read about dinosaur hippos that used to live here and how alien plants colonised the burgundy beach. The relics lost their land and died out.

Tjarlie parks his feet in the sand. ‘Can you feel that?’ He shuts his eyelids. ‘Sometimes, where we stay, ’n man can feel the same cool breath. Even if it’s just for a few seconds. But ’n man can feel it. And it’s like everything is quiet for those few seconds.’

I know what he is talking about. This place has a calmness that forces you to worship the mundane. My attention is on the ripples of water ribboning under the mass of gravity. It is not under pressure to be the colour of water. There is a freedom to be whatever it wants, be it melted butter or Baker-Miller pink. I wonder how the river gets its waves laid without a durag. It babbles the story of how I learned to swim at Stukkende Brug.

I was nine years old, tracking my cousin and his friends to Stukkende Brug—the river separating magnolia from vineyard. The ruins of an ancient aqueduct shaped the water into a brown swimming pool with concrete sun loungers tanning in the after-school rays. My cousin chased me back with my mother’s private parts serving on his tongue. He must have thought that I would snitch about them smoking slow boats. Daniel convinced him that I should stay. I still remember Daniel. His chin drowned in an ocean of bronze mane. His eyes were puke yellow on the roof of a skyscraper. He always looked high. Sun-kissed fingertips lured me to them. Daniel bought me a packet of La Bamba Beef so that I would not tell on my cousin. That day, Daniel taught me how to float. He told me to get comfortable in the brunette water, to make my skin lantern paper. The water was his second home. My head rested on his woolly shoulders. Hands that were also sandpaper travelled down my spine seeking my lower back. He moved back slowly, but I weighed too much for the copper. Daniel was patient like Miss Honey. Later we went to the river alone. He promised to show me how to do somersaults from the wreckage of the collapsed bridge. I was too scared of the earth quaking under my feet.

‘Let’s see who can hold their breath the longest.’

The water did not want to hold me down. He then grinded leaves into smoke and poured it in my nostrils. My lungs crawled out.

‘Het jy al geskinny dip,’ he asked me with inviting eyes. Our clothes dripped of bone and marrow. ‘Naked,’ he pointed at my jockey.

I saw what my body will morph into one day. A tall marshland with lotus petals for tissue. The river swallowed our salmon. Liquid grew hands. Hands touched everything palpable and subterranean. For a long time, I convinced myself that because I enjoyed it, nothing bad happened. Compared to this ocean, a laaitie’s consent is a puddle. Daniel gave me an over-ripe banana to shut my mouth a vault.

Tjarlie is rolling a joint. He is very religious about using Bible pages as rolling paper. Apparently, it takes flame easier. At this point, we have Genesis and Exodus engraved on lung tissue. We just started burning the haunting scripture of Leviticus. Money grows on his long fingers. You do not ask a brown boy where the money comes from and you never utter a word when you do know. He is the merchant and the stoner. I am the smoker and the prayer. Sometimes he asks me to keep it in my Karrimor, but he does not want me to sell.

‘Why not? I also want to make kroon,’ I one day told him. ‘My broe, you hear how you sound right now?’ He shook his head. He always says that I am going to make it out of here. In this town, there are people who stay and then there are people who leave. According to him, I am just here temporarily. ‘You have the kop to go get a degree, and I’m gonna be trapped here with two choices: Either I matriculate to go to the tjoekie, or I die.’

My school shirt is origami folded on top of my tattooed bag. I ask him if he knows that the Afrikaans word for ‘Tipp-Ex’ is ‘flatterwater’.

‘And the Afrikaans word for “Cutex” is “naelpolisie”,’ he laughs with dilated eyes.

Tjarlie’s grey trousers hang over a tree branch just as his grandmother taught him. He does not talk much, but when his jaws do move, it is always about her. He would brag about her peppermint kisses, how she would read her stars in the Huisgenoot, her belt hands, Bella koortjies and how he could do nothing wrong in her eyes. Then Covid came and now all he talks about is keeping her grave clean. My mouth never stops moving, I know, but it is never about myself. I hide behind the void that comes with many words. Will we still be friends if I let him in? Surely, these cracks are not a welcoming sight. I am a grade higher than Tjarlie, but he is older. He enjoys calling himself my boeta. Tjarlie taught me how to fight by punching his fist in my face once after school. We became instant friends. He showed me how to shave my beard with one of his grandmother’s Bic razors. It was a dry cut. Here, boys do not bother with creams and softness.

‘Broe, you need to shave in the direction that the hair grows. Didn’t your tôrpie teach you that?’ Fresh fades with naked cinnamon torsi in front of a cleft full-length mirror. ‘Are you bleeding?’ He names the rosary peas blooming out of my chin. I guess it is part of the process. This must be how vulnerability feels. You grate flesh from meat. An écorché swims in its own blood and insecurities. ‘Moenie worry nie. I’ll sort the cuts out with spirits.’ A wild fire erupts on my face. I cannot show pain. At least Deddie taught me that.

There is no one at the Bergrivier. It is just the two of us and crowds of palm trees scrapping against the zaffre sky. Tjarlie sits legs crossed in a trunky with seven dragon balls on it. The sun leaves hickeys on his muscles. A stab scar on his abdomen smiles at me with a passion gap. I remember the first time I saw him nude. It was in General’s shack. The last day of our initiation. The inductees made a sumo moon in a barren living room. Our bodies were bare for picking. Puddle-wet, crammed together in the chockey. My wrists grew leaves over my penis. Air bulldozed my chest, passed my neck and congested my mouth. Tjarlie stood stiff next to me. General sat in the middle. His one good eye scanned every syruping body. In his palms, he elevated a loaf of baked bread, which he then broke into twenty-eight pieces.

‘Crumbs,’ General said as he made his rounds.

My eyes noticed Tjarlie’s Shenron.

‘Is tough to make a living out of fokkol.’

The crumbs built a cathedral on a silver tray. He offered it to us. ‘This is my body. It’s your body and the bodies of your broese.’ He instructed us to eat.

‘This life will chop you into pieces and devour you.’ General removed his eye patch to reveal a granite marble. ‘Maa nou het ôs vi mekaa! Every time you eat this flesh, do it with the willingness to stand for your manskappe.’ He walked towards me. The ground hit my eyes. ‘If you swallow this daite, you testify that your body does not belong to you anymore.’

When we were all done, he took a zinc pillow with a black tap that vomits red wine into a bucket. He then took two deep gulps. ‘Bloet, getuies.’ His merlot lips threw vowels and consonants into the air. A eulogy stuck to the bungalow’s metal ceiling. ‘The streets are flooded with our blood. This dop is the agreement that we make tonight …’ he pointed to the sun rising under his Adam’s apple, ‘loyalty.’

Suddenly, General turned into a feisty evangelist preaching at an open-air service. ‘Our own blood wrote us off. If you suip, you agree that your blood will flow for your broese.’ The room has a ruby filter. ‘Ondou, we belong to each other now.’

Mathayus and Mr Krabs mate in the sky. Tjarlie looks like a mermaid in the glitter, half man, and half fluid. Harboured to the banks, I am watching how the orchestra swells around him. He seems in harmony. Waves push softly against concrete, intentionally utilising gentleness to try and crack open cement or flay skin. Now Tjarlie is playing dead, floating on danger. The coffin waters carry his corpse like pallbearers. Even in water, our lifeless bodies look native. I did not know that dead brown boys are buoyant. I did know that our death is synchronised. Tjarlie drowns to the bottom and digs a grave out of debris. I lean over and whisper to the river. Keep a place for me. I will sleep next to you under the ground duvet. We can most probably make a Christmas bed. All of us: Nathaniel, and, Leo, and, Boetjies, and, Nolan.

‘Gan jy nie swem ie,’ Tjarlie’s hands courier a mountain stream at my corduroy desert. It leaves another mark. I can swim, but I do not like swimming in stained water or the salted juice of carnage. Rivers have python mouths that slurp boys like me whole. ‘Are you scared of water, my broe?’ He bounces on his one leg to unclog his ears. ‘Ek wil mos sê. Whole time I smell something stink.’

I want to tell him that this is a morgue.

His shadow falls on me, ‘So you’re forcing me to throw you in now?’

My cadaver is still in the water. No one came to identify the body. Tjarlie grabs me and pulls me away from the shore with his rip current arms.

‘And now,’ I ask trying to pull myself loose. ‘What are doing? Naai, broe. Los my!’

He tries to lift me, but I anchor my feet in the ground, fork my fingers in his sides and trip his right foot. With me on top of him, we land on the itchy green mattress. He puts my neck in a chokehold and snakes his legs around mine. We are rotating bodies in a war to be on top. Tjarlie is victorious. There is no surprise there. Our lungs scramble for air. I watch the gears spinning in his chest. He fetches my eyes and brings them to his face.

‘What?’ A question mark replaces eyebrows. My heart lusts for a prison break out of a rib cell. Tjarlie does not answer, but I can hear his heart beatboxing. For some reason I understand that this is the start of nothing, but also the end of everything. His citrus lips blow in the air. I unearth my nails from his sides and cruise my tallest finger up a flooded spine, until I reach his blushing cheek. Tjarlie closes his eyes, but mine are Kodak open. The floor trades soil for feathers. The sky reflects the river. Both of them are shedding skin to divulge pink flesh. For a few seconds we forget about the danger. To Eve the apple was just that. Jerobejin did not know that mangoes are kidney-shaped.

Tjarlie sinks his face in my collarbone as if my torso is a homecoming celebration after a long day. My arms shield his back. The trees blow a breeze on our ceramics.

He whispers in my ear, ‘This is how the water feels.’

~~~

- Keith Oliver Lewis is a poet from Smartie Town, Paarl. His work speaks to the lived experiences of Coloured/brown people in South Africa. He uses words to investigate and reveal the root of the social ills plaguing his community. Lewis’s creations focus on reimagining the forgotten histories of his people and humanising their current surreal existence. He sees memory as an archive to bring healing from trauma and loss.

Oh wow! I am speechless. This is electrifying. Congratulations Mr Lewis. I am in awe!